U.S. Attorney Mike Hurst announced Project EJECT (Empower Jackson Expel Crime Together) on Dec. 7, 2017, with then-Jackson Police Chief to his right and Christopher Freeze, Special Agent in Charge of the FBI in Jackson, to his left. Photo by Stephen Wilson.

In November 2017, Ledarious Anderson apparently thought he was going on a date with a woman named Alexus Guster, but he was headed to a set-up. Two men, Darrell Moore and Cedric Winfield, allegedly told Guster that she would receive a portion of the take from a robbery if she could get Anderson to meet up with her. Guster agreed and lured Anderson via Facebook, an affidavit shows.

Guster told Anderson to meet her at the Arbor Park Apartments near Clinton, where she stood waiting with Winfield, whom she introduced as her brother when Anderson pulled up in his 1999 red Pontiac Grand Am. Guster and Winfield talked to Anderson from his passenger side, and while he was distracted, Moore came to the driver's window with a firearm. Moore pulled Anderson out of the car and took $200, court documents say.

Anderson apparently ran away as Moore shot at him. Winfield then drove off in the stolen Grand Am, and Guster left with Moore in his car, authorities say.

But it wasn't just the robbery, or the aiding and abetting, or the shooting that landed the trio in federal court, where they are much more likely to be sent away to faraway prisons outside Mississippi. Rather, the fact that the Grand Am had been transported, shipped and received through interstate commerce—meaning it crossed a state line—makes Guster, Moore and Winfield early offenders charged under U.S. Attorney Michael Hurst's "Project EJECT."

"Carjacking is a federal crime because the car was manufactured in interstate commerce," Hurst said in his office in February. Thus, so was a plan to steal a vehicle made outside the state in this local incident.

Hurst has charged 32 others since he first announced the anti-crime initiative in late 2017, like Bobby Ray Mahone and Latesha Vavuris, who allegedly held up a Family Dollar store in October 2017. Like the other case, it is not robbery per se that put them within Hurst's jurisdiction rather than the more typical route of state or local criminal charges, even for acts committed with guns. Their robbery allegedly interfered with interstate commerce because customers from outside the state can purchase items inside the store.

Every single case Hurst is pursuing under Project EJECT involves illegal use or possession of firearms in some way under an initiative U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has resuscitated from the years before Barack Obama became president.

'Making America Safe Again'

On a cool, breezy and overcast morning this past December, U.S. Attorney Hurst called a press conference on the steps of the U.S. District Court in downtown Jackson. President Donald Trump had appointed Hurst in a second wave of U.S. attorney nominees and described him as sharing "the President's vision for 'Making America Safe Again,'" the June 29, 2017, White House announcement reads.

A sign with a large red button and "Project Eject" written across the center leaned on a tripod easel. He had invited media, Hinds County District Attorney Robert Shuler Smith, Hinds County Sheriff Victor Mason, FBI Special Agent in Charge Christopher Freeze, and clergy to stand by him as he unveiled Project EJECT (Empower Jackson Expel Crime Together).

"Today is a new day," Hurst began, adding, "(T)he message to violent criminals in Jackson is simple: you break the law, you terrorize our neighborhoods and you will be ejected from our community."

Hurst's goal to "eject" violent criminals into federal court and then prisons outside the state is much like Project Exile in Richmond, Va., in the 1990s, which sent felons into "exile" for firearm violations. Freeze of the FBI, in fact, worked for the agency in Richmond at the time, back when James Comey was the U.S. attorney leading the program there. Freeze started pushing a version of Exile in Mississippi soon after he arrived in late 2016.

"Project Exile was founded and based on the concept that if you're a convicted felon, caught in commission of a crime, with a weapon, there's a five-year automatic sentence to federal prison," Freeze told WDAM in Hattiesburg in April 2017.

"I've talked to some of our partners in the Jackson area and some of our state partners to kind of hear them out and see if they think it would be viable," Freeze said then. "The U.S. Attorney's Office would be a big part of that, so certainly their willingness and ability to be a partner in that regard will be something we are discussing and will further discuss with them."

Freeze found a willing partner in Hurst, who said on Dec. 7 that a dozen special agents from both federal and state agencies had already begun collaborating with local law enforcement and going out to crime scenes with JPD officers to identify crimes he can prosecute. Those cases go to Hurst's office, and a task force determines if there is enough evidence to prosecute suspects in the federal system. Hurst said then that authorities will lock suspects up immediately in detention without bond, and law enforcement will not cut a deal so the suspect could be out in a few months.

Here's where the ejection comes. Once convicted, the theory goes, the felon would spend time without parole in the federal system "far, far away from Mississippi so that they cannot continue their criminal activity behind bars," Hurst said in December. The federal system no longer offers parole.

The idea is that the criminals would be away from their criminal networks and, thus, be likely to commit less crime. They would also be removed from their families and existing support networks while in prisons known for rough gang activity, a problem even Hurst described in an interview.

The state involvement comes at the hands of DA Smith, who committed to provide cases that can be prosecuted federally in order to free up the his resources. He is scheduled to face trial himself in Rankin County in September 2018 for domestic-related felonies involving a firearm.

Then-Jackson Police Chief Lee Vance also stood next to Hurst at the announcement to show support for the initiative. Vance, who later resigned at the end of 2017, said at Hurst's press conference that his "greatest wish" for the strategy is that a young man in Jackson rethinks a life of crime and will rethink his actions after watching others go to federal prison "for a long time, perhaps thousands of miles away from here."

Vance's replacement, Interim Police Chief Anthony Moore, has been tight-lipped on virtually everything, including Project EJECT, despite the Jackson Free Press' requests to interview him since he took over the position on Jan. 2.

Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba has offered few public statements on Project EJECT, despite public criticism of it. The same day the interim chief was announced, Lumumba told the Jackson Free Press that he and Moore had not yet had a chance to discuss it, but the mayor emphasized that the two spoke about ensuring good relationships between police and community.

Meanwhile, citizens are forcing a public conversation about Project EJECT.

City's 'Sphere of Influence'

Calandra Davis approached the wooden podium during the time allotted for public comments at the Jackson City Council meeting on Feb. 27. She said she moved back to Jackson a year ago and is not pleased with local policing strategies—including Project EJECT.

"During my time back, the police in the City have implemented the Project EJECT program, and there have been at least seven officer-involved shootings," Davis said. "And to realize that this program and these shootings affect African-Americans disproportionately should raise concern for all of us...."

When Davis finished, the mayor wanted to clarify the City's involvement with Hurst's brainchild.

"Project EJECT is (not) and has never been an initiative of the City," Lumumba said. "... This administration has never said it is in favor of Project EJECT, we have never made any comments on Project EJECT. In my opinion, it may be out of our sphere of influence. What our police department is tasked with doing is investigating cases."

The mayor added that the City can neither make the feds prosecute cases nor stop them from prosecuting them in either federal or state court. He did, however, offer some criticism of Hurst's approach.

"I will say that some of the comments that were made during the (Hurst) press conference where it talked about people not getting bonds and everything else was inappropriate," the mayor said then. "I don't think that it is even within the sphere of influence of the people who said it because a prosecutor doesn't dictate whether somebody gets a bond—a judge dictates whether somebody gets a bond."

Hurst agreed with that statement in his office in February, backtracking from the promises of his earlier press conference. "Oh, yeah, people have misconstrued what I said at the press conference," he said. "... We are only a part of the judicial process, and our part will be to move for detention." He pushed back on the suggestion this his promises meant violating people's rights to bond; they will suggest no bond, he said. "We're moving for detention, and the judge makes a decision based upon the facts."

Hurst also made it clear in his office that he knows the federal system does not offer parole, so it cannot be rescinded.

At council, Calandra Davis also wanted to know if the mayor was explicitly in favor of Project EJECT, which is focusing solely inside Jackson and in no other parts of the state so far, Hurst said. Council President Charles Tillman of Ward 5 did not let the mayor respond, grunting into the microphone to vocalize his disapproval, and shaking his head "no" to illustrate it further. The mayor did not get to speak further on the EJECT strategy.

But, before he was interrupted, Lumumba added that Project EJECT is a federal initiative from three or four years ago, when former U.S. Attorney Gregory Davis was in office, which he had told the Jackson Free Press earlier, saying it was a program the Obama appointee oversaw.

In his office, Hurst also pointed out that Davis had used the same approach as EJECT but by a different name. "My predecessor Greg Davis had really focused on violent crime his last few years in Jackson," Hurst said. "I'm really building off what he had started and with direction from the president and Attorney General Sessions. They really wanted to make violent crime a focus of this administration."

For Sessions, that meant bringing back a controversial approach to prosecuting gun crimes federally with mandatory sentencing as part of the innocuous-sounding, but highly controversial, Project Safe Neighborhoods initiative, which predated Obama and Davis and drew charges of racial bias.

‘Police vs. Black’: Bridging the ‘Racialized Gulf’

The divide between police and black communities is about more than white cops.

"I couldn't think of a better place to start that here in the Southern District of Mississippi than in Jackson," Hurst said in February. "Seeing what Greg had done and how federal law enforcement in particular had worked with the state and locals, we thought it would be good to reboot the old Project Safe Neighborhoods into our own initiative called Project EJECT."

Obama Era to Trump Era

Former U.S. Attorney Gregory K. Davis said Project EJECT is not, in fact, the exact same, and added some nuance to both Lumumba and Hurst's use of his name to justify the enforcement approach.

"There have always been, sort of, initiatives in place to address violent crime," Davis said in a March 13 interview. "And I think the Jackson Violent Crime Initiative that we started ... was kind of a prelude to some of these initiatives that are going on now. I think (Project) EJECT may have just been an initiative with the current administration. They may have changed it up somewhat, but it's still a program to address violent crime."

Davis said his iteration did not specifically threaten to send convicted criminals far away from Mississippi. Even if a judge recommends people serve time as close to Jackson as possible, the Yazoo City facility is the state's only federal prison for them. The other federal prison, in Adams County, is mainly used for immigration. So, people would likely go beyond state boundaries if convicted of federal gun crimes. That's just the nature of the prison system, Davis said.

"We didn't come out and say 'we're going to eject you from the City of Jackson,'" Davis said. "Our issue was more so that violent people need to be prosecuted, the law needs to be enforced, and once they're sentenced, they will be sent to a prison. More than likely that would be at a different location other than a local area."

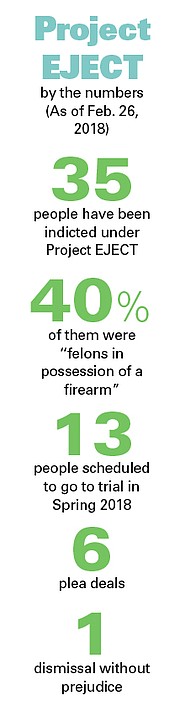

Davis' Violent Crime Initiative aimed to remove violent offenders from the streets to make communities safer. A lot of the charges under his initiative were similar to the ones Hurst is pursuing. Forty percent of the people charged under Hurst's Project EJECT as of Feb. 26 were felons in possession of a weapon. In a press release from August 2015, seven of the 10 people listed for either charges or indictments under Davis' Violent Crime Initiative were previously convicted felons in possession of a firearm. Five of those 10 people are serving time in federal prisons now.

At either a judge's recommendation or luck of the draw, some of the aforementioned 10 went to Yazoo City. Others went to Arkansas, West Virginia, Florida or Georgia. Davis did not set out to have people who commit violent crimes sent far away like Hurst; that is where they landed.

Davis explained that federal-local partnerships to rein in violence are not new; they get recycled and rebranded with each new administration. He modeled his policies toward violent crime after national initiatives from Obama-era U.S. Attorney Generals Eric Holder and Loretta Lynch.

Holder launched a "Smart on Crime" initiative in 2013 to de-prioritize prosecuting non-violent crime and encouraged U.S. attorneys to use scarce federal resources mainly for violence prevention to help prevent the crime before it happened rather than rely on the threat of arrest and prison, which can actually lead to worse crime.

To that end, Lynch added Jackson to the Violence Reduction Network, which the U.S. Department of Justice framed as a "comprehensive program" to leverage resources and provide a "hands-on approach" to reducing violence in targeted cities across the nation. Little came of it here because it was late in the Obama administration. The City has not announced any programs or resources associated with it since Sessions became attorney general.

Hurst's initiative is more consistent with Sessions' law-and-order, tough-on-crime positions, which focus on enforcement over prevention, at least so far.

In February 2017, President Trump signed an executive order directing Sessions to establish and to appoint or designate an individual or individuals to chair a task force on crime reduction and public safety.

"A focus on law and order and the safety and security of the American people requires a commitment to enforcing the law and developing policies that comprehensively address illegal immigration, drug trafficking, and violent crime," the order reads.

By June 2017, Sessions had his partnership in place to go after gun violence. In October 2017, Sessions sent a memo to all U.S. attorneys reviving Project Safe Neighborhoods, a George W. Bush-era initiative he deemed successful, which had cost the government about $2 billion since its inception in 2001.

That strategy propelled Hurst's office to secure indictments such as Guster's, Moore's and Winfield's under Project EJECT rather than allow them to go to state court. When asked if he was fearful or hopeful about how things will go in the U.S. Attorney's office now, Davis seemed torn.

"I'm both," Davis said. "I'm hopeful the good things we did will continue, and ..." Davis paused for a beat, choosing not to delve into any qualms he may have had. "Let's just say, I'm hopeful that it will continue," he added.

Ceasefire Fires Back

U.S. Attorney Hurst, who comes across as perennially cheerful, now has the Project EJECT sign on an easel outside his office in the sleek federal courthouse building in downtown Jackson. In February, he explained the inspiration behind Project EJECT.

"On the prosecution side, we're not reinventing the wheel," he explained. "We're taking a lot of what has been done in other cities, whether it be Richmond (Va.) with Project Exile or Boston with (Operation) Ceasefire or Baton Rouge. A lot of cities have done this—focusing federal resources on local violent crime."

The violence expert who helped design Operation Ceasefire—which launched as the Boston Gun Project in 1996—did not mince words a couple weeks later when asked about Project EJECT and its earlier models in Richmond, Va., Rochester, N.Y., and other cities in the U.S.

David Kennedy disdains Project Safe Neighborhoods as an anti-violence approach, calling Sessions' crime strategies "evidence-free", despite violence statistics its proponents cite to prove otherwise. Not to mention, he said, strategies like EJECT and Exile have little to do with his Ceasefire approach, which is often referred to as the "Kennedy model" of violence deterrence.

"One of the innumerable mistakes is to say that Project Safe Neighborhood was built on Kennedy's work," Kennedy said in his office at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York where he is a professor. "... That's not right. It was in a small way based on my stuff. ... We produced the first research that really showed there was such a thing as illicit markets in firearms."

But the approach that became Project Exile under U.S. Attorney James Comey in Richmond ignored vital aspects of his team's work to decrease group violence, Kennedy said, calling his work "a partnership approach focused on groups."

"The other (approach) was Exile, which actually has its roots in opposition to my work," Kennedy added.

Unlike Operation Ceasefire, Project Safe Neighborhoods declined to focus on how violent people get firearms, whether legally or illegally. The Exile approach, which was also endorsed by the National Rifle Association, puts the prosecutorial onus on the street-level shooters with little attention to where the supply of weapons came from or how to stop it. That led to charges of racial disparities, and contributed to increased distrust between police and communities of color, Kennedy said.

The Operation Ceasefire approach, which Kennedy's team now brings to cities through the National Network for Safe Communities, is about prior engagement with those believed likely to commit gun violence, offering them help and services, and also threatening them with arrest on the state or federal levels if they or their associates commit violence. It is also about identifying illicit markets for weapons. And those trafficking the weapons aren't usually the young black people who get caught up in federal Exile-type enforcement.

Initially, the NRA liked his approach, Kennedy said, but redirected its support away from a program that identified illicit markets to supporting the street-level federal arrests the Bush administration adopted. Those arrests sent a disparate number of people of color to a gang-packed prison thousands of miles away for additional years, while not bothering to also focus on how they got the guns in the first place. Kennedy also said the federal prosecutions were brought unevenly, deepening distrust in communities toward law enforcement.

In his office, Hurst backed away from Ceasefire when asked if his alliance was also including the services and prevention side of the strategy, as Kennedy's approach requires. "It's really not something, that aspect of Ceasefire, we have not really considered. (EJECT is) really going to be more in line with Exile. It's almost Exile Plus in the sense of Exile was very strong. But I don't know how much of the prevention and, yeah, re-entry they did, but it's hard to argue with their numbers during the time."

Kennedy does argue with the numbers of Richmond's Exile and all its clones. Violent gun crime did fall dramatically in Richmond then, but it did not in other cities that emulated the strategy, raising his suspicion that more was going on, he said.

"The reason we know Exile doesn't work is ... because there's a small body of really good formal evaluations ... that say it doesn't work," Kennedy said. "I'm not aware of any place where (Exile) was associated with violent crime reduction."

"What else was going in Richmond at the time? Was there something else that accounted for the reduction?" he added.

Jackson ostensibly tried an Operation Ceasefire approach at one time called "MACE" supposedly modeled on Baton Rouge's BRAVE strategy, but a Jackson Free Press investigation found that local law enforcement just left out the services and outreach components and used the resources for massive enforcement, which violates the principles of Ceasefire.

'The More That You Learn'

Wearing the red-and-white top hat illustrated in Dr. Seuss' "The Cat in the Hat," U.S. Attorney Hurst posed with Jackson Public School students at Johnson Elementary School for Read Across America Day on March 2. In his later tweet with snapshots next to the majority-black class, Hurst quoted from a different Seuss book.

"The more that you read, the more things you will know," the U.S. attorney tweeted. "The more that you learn, the more places you'll go."

It was the second school visit Hurst had made in two weeks. On Feb. 21, he spoke at a Teen Town Hall meeting hosted by Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, a subsidiary of Washington D.C.-based Council for Strong America at Jim Hill High School with Interim Jackson Police Chief Anthony Moore.

Hurst also tweeted after that event, which students there say did not focus on Project EJECT, with a nod to his new initiative. "You can do absolutely anything you put your mind to!" Hurst wrote on Feb. 21. "Empowering Jackson Expelling Crime TOGETHER #ProjectEject."

Juan Cloy, a former Jackson police officer who was assigned to the FBI's Safe Streets Task Force, is the Mississippi project director of Fight Crime, a nonprofit to help prevent youth crime. Cloy was at Jim Hill and said the event went pretty well.

"The whole gist of it is to first of all bring youth and police closer so they can have some common ground and some understanding of what each other needs from each other," Cloy said in February.

Cloy said Hurst showed up at the town hall because he cares, and that conversations between law enforcement officials and children help build trust. Cloy said the event was an informational dialogue rather than a scare tactic, per se.

Still, "Hurst said in the town hall (that) he didn't want to see young kids going to federal prison, Cloy recalled.

The conversation did include what can happen when someone enters the federal system. Cloy said he did not know about the accuracy of Hurst's threats about prison at the December EJECT announcement. From Cloy's experience, particularly with repeat offenders he arrested on the federal task force, a lot of prisoners ended up going to the federal prison in Yazoo City. Where you end up just depends on the judge and the Bureau of Prisons, Cloy said.

In a perfect world, Cloy said, no one would need to go to prison. He wants to approach the justice system with the kind of equilibrium David Kennedy talks about—balancing the stick of arrest with compassion and programs that preempt people from entering the system, especially kids.

"So what we're trying to do is keep young people from even being introduced into the federal system or into the local or state system...," Cloy said.

"That way we don't have to worry about any acronyms at all, right?"

Greg Davis agrees. While in office, the former U.S. attorney had an initiative called LEAD: Mississippi's Legal Enrichment and Decision Making Program. Through it, he spoke to students around the state about staying on the right path—but still focusing on what would happen if they did not.

"One of my primary goals as a prosecutor is to prevent crimes from happening in the first place," Davis told a group of students at N.R. Burger Middle School in Hattiesburg in October 2014.

"Educating students about the social and legal consequences of their decisions is essential to reducing negative behavior and making our communities safe," he added.

Hope and Consequences

When Hurst announced Project EJECT, he grinned as he drew connections between his initiative and basketball—particularly what happens when you commit a foul against another player.

"Goodness knows, I had my fair share of fouls," Hurst said in December. "But, if you intentionally, flagrantly violate the rules, you will be ejected. That's the consequence. What we're announcing today with Project EJECT are consequences, but also hope."

Hurst added that even if you get ejected from a basketball game, you don't have to leave the sport for life. Rather, you can come back the next game and abide by the rules. He sees the same thing happening for people sentenced far from home under Project EJECT.

"Come back after you serve your sentence, be rehabilitated, abide by our rules, and we will welcome you back with open arms in our community," Hurst said.

Not everyone who has been in prison or involved with efforts to rehabilitate criminals takes such a rosy approach, however, especially to sending prisoners far away from their families and expecting them to come back as better citizens ready to work.

John Koufos, the national director of re-entry initiatives for the Koch family-funded Right on Crime, was in Jackson recently to urge conservatives to support prison reform and re-entry. A former felon in New Jersey, Koufos slammed the idea of ejecting offenders to another state.

"Many times ... you've got people locked up all over the country. How are you supposed to re-integrate these folks back into the community when they're in Kansas?" he said at the Old Capitol Inn.

Hurst holds firm, though, that the threat of being shipped away can lower violence. "That's kind of the deterrent effect that we're looking at here. I understand the opposing arguments that, and that's definitely a concern," he said in his office.

Promising ejection is key to the strategy, Hurst emphasized. "The thinking behind that is to send a message that we're going to eject you from our community," Hurst said in his office. "I know that's tough love, but it's combined with the fact that if you want to come back and follow along, we really will help you re-enter society. It can't just be tough love; it's got to be that (promise of help)."

Re-entry: Trend or Reality?

The non-law enforcement piece of Project EJECT involves the faith-based community, nonprofits, neighborhood associations and businesses, Hurst said. In fact, local stakeholders represent the "T" in EJECT—together. Hurst wants business owners to give people a second chance once they have served their time and returned.

He does talk about getting to the root cause of crime through prevention, education, rehabilitation, communication and collaboration, but it is not built into Project EJECT with federal resources and strategies behind it. Hurst made his limitations clear, and leaned on the community behind him instead to achieve better communities.

"We don't have all the answers, guys," Hurst said in December. "Project EJECT is fluid, flexible for a reason so we can adapt to the changes and circumstances, and frankly rely upon the expertise of these men and women standing behind me."

Jeff Sessions has been less clear, quiet even, on re-entry, especially when compared to his predecessors. In his October 2017 Safe Neighborhoods memo, Sessions promised a "comprehensive approach" to public safety, including prevention, enforcement and re-entry efforts. But he mentions re-entry only twice, and suggested supporting locally based groups' re-entry efforts, as Hurst later echoed.

That is, the feds bring the big stick, and locals fund the prevention carrot.

Both Holder and Lynch had zeroed in on re-entry efforts as well. Lynch, in particular, had a National Re-entry Week that Davis implemented here in Jackson, he said. He stressed the importance of re-entry efforts for both the offender and the citizens in community.

"Re-entry is important because what happens is this," Davis said before pausing and releasing a long sigh. "Once someone has paid their debt to society, they need to have an opportunity to re-enter society and be a productive member.

"If they re-enter society and they're not prepared, unable to get a job, unable to have a driver's license, unable to get health care needs, unable to get whatever services that they should have to allow them to be productive, then they run the risk of re-offending."

Recidivism after spending time in violent prisons is an epidemic. "If somebody re-offends, they have another victim ..." Davis said. "And that's one way you reduce crime, by not having people who get out re-offend."

In a recent interview, Phillip Goff, co-founder and president of the Center for Policing Equity at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, delved into the risks of removing people from their social supports by way of federal projects like EJECT.

The criminal-legal system tends to be comprised of the poorest, most vulnerable, poorly educated, least advantaged and least connected to opportunities, and those prosecuting them do not tend to be of that demographic, he said in a phone interview.

"The people making decisions about removing folks, shunning folks, and excommunicating them from their homes are often not the same people who are in community with those committing crimes," Goff said. "That's a fundamental flaw with the way that we handle the criminal-legal system right now."

Goff does not consider programs like EJECT that remove people from their support networks to be forward-looking; rather, they make re-integration more problematic, he said.

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

"What are the chances of when that person gets out, their lives can be transformed?" Goff said.

"Who among us ... can be removed from social networks and become better for it? Any policy that removes someone from their social support is not a policy that is aimed at making them more likely to succeed when they re-enter...."

Thirteen people are going to trial in the next two months before a federal jury of their peers to decide whether they will be among the first ejected from Jackson under the strategy that Hurst, Freeze and Sessions embrace, with support from the City of Jackson.

Alexus Guster already took a plea deal for her part in the car theft, but Cedric Winfield and Darrell Moore will go to trial on May 8, and if found guilty, they could be off and away, far from their families.

An investigative fellowship through the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at Penn Law School assisted with research for this article. Read more solutions at jfp.ms/preventingviolence.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus