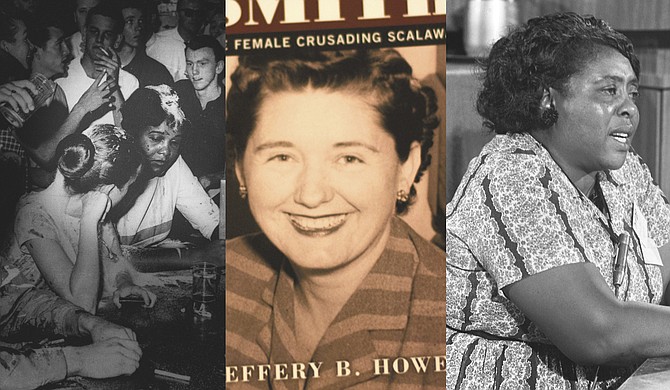

Left to right: Anne Moody, Hazel Brannon Smith and Fannie Lou Hamer were Mississippi women who risked it all to help Mississippi become a better place. Photos courtesy Fred Blackwell; Cam Bonelli; Warren K. Leffler, U.S. News & World Report Magazine/Public Domain

I'll never forget the night Mississippi voters handily defeated the Personhood initiative. I was at my friend JoAnne Morris' house where we usually watch election returns. I was cautiously optimistic because I'd had a front-row seat to the most impressive display of collective woman power I had ever witnessed in my home state. I'd published piece after piece—news, analysis, opinion—by and about the pushback by the "grassroots mamas" against an extreme attack on abortion rights, in-vitro fertilization and birth-control pills.

This was an exhilarating effort in 2011 because women—Republicans, Democrats, independents, older, young and of various races and ethnicities—just decided they weren't going to allow this effort chaired by then-Lt. Gov. Phil Bryant to squelch their rights to choose and even stay alive in a political move to control women.

As the votes came in, and the vote against Personhood crept up to 58%, JoAnne and I were cheering in her living room. Yes, we were thrilled to see radical legislation going down, but also because Mississippians were standing up, with women in front, to use our power rather than cowering in hopelessness for our state.

I loved seeing all the stunned tweets that night from outsiders astounded that Mississippi could pull off such a hearty defeat of radicals who think it's fine to treat women like a "handmaid" whose approved use is to have babies on demand and obey men. Women led this movement, most of them mothers. Some were executives; others students. They met in each other's living rooms and planned how to fight back.

Then the mamas won. We all won. Mississippi won.

We all know women do not "win" often in Mississippi, certainly not for standing up for women and our choices or to men who make things worse for us all. We are supposed to be perpetually polite and submissive toward men, too many of whom melt down if we challenge them, even for behavior that has negative effects on the public good. We are not supposed to self-promote or "show off" our sass, our training or our intelligence in public, or call out lies. We're to agree and apologize, no matter what.

But Mississippi has long had women warriors who don't flinch at attempts to make them shut our little mouths, who stare back, who write scathing columns, who get the hell beaten out of them in jail cells without editing one word they still need to say afterward. Our state may not be big on naming buildings after those women or erecting public statues of them, opting instead for angelic marble women bending lovingly over their Confederate heroes like Sen. Jim Eastland's racist mama got erected in front of the Mississippi Capitol.

During the pandemic, Todd and I started road-tripping to counties around Mississippi getting to intimately know my home and his adopted state—from local history to vicious lynchings, namesakes of towns to less-known fighters for justice and freedom. We retrace the steps and visit grave sites of heroes and scoundrels, filling in blanks in history as we go. Even as confronting just how horrible white supremacists (not just the rednecks) were here, still better is "meeting" courageous women leaders who believed enough in our state's potential to lay their lives on the line for it.

We went to Ruleville twice to not only celebrate Fannie Lou Hamer's life and the badassery of telling her story at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, but to better understand what the former sharecropper was like back home. We learned how she dug into the roots and results of racism in her hometown, helping others improve economically and have enough to eat. She taught the children she couldn't have—a white doctor had sterilized her without permission, taking away her reproductive choice and freedom forever—to hope and believe that Black lives matter, too. It seems that half of Ruleville is now named for her, and she has a statue—rare for a woman in Mississippi and the U.S.

Last week, we retraced civil-rights activist Anne Moody's steps down in Wilkinson County, where she started cleaning white people's houses when she was 9, even as white people were killing Black people around her with no punishment.

In her vital book, "Coming of Age in Mississippi," Moody talks about how the white woman she worked for as a teenager responded to news about the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till up in Money. Moody's boss wasn't aghast at Till's vicious murder; she started having "Guild" meetings in her home, serving tea to proper white ladies conspiring against the NAACP and dropping the n-word so her worker could hear. A strip of Highway 24 and her childhood street in Centreville is named for Moody now.

In Lexington up in Holmes County, we're digging deeper into Hazel Brannon Smith, a white editor whose memory gives me strength when the North Jackson (or now North Mississippi) Angry Men's Club members start kvetching because I'm so opinionated or my reporters so thorough.

Hazel herself started out as a fashion plate and a segregationist; she ended up taking on corruption, winning a Pulitzer for her columns about local racist police violence and daring to print the original Mississippi Free Press, a Civil Rights Movement newspaper with a multiracial staff that powerful white people despised and terrorized because they dared tell the truth.

A group of white teenagers even burned a cross in Hazel's yard, and powerful white men started a rival newspaper to destroy her successful business. They succeeded. She lost everything and died penniless after suffering from Alzheimer's.

These Mississippi women, and others, give me strength. When I'm frustrated—like when Mississippi's first woman U.S. senator votes for a U.S. Supreme Court justice who may well help force Personhood on the whole nation and end health care for our neediest—I draw on these women's memory, and examples for strength, tenacity and a renewed belief that our state's best days are ahead. Freedom, then and now, is a struggle, and sexism still insists that women shut the hell up and avoid the fight.

I don't know if it'll be enough, but I know that women are again going to roar this Election Day. And that includes here in my home state. I'll meet you at the polls.

Follow Donna and Todd's discoveries on his Driving History channel on YouTube and soon at donnaladd.com.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19