JACKSON — Finding a way to prevent the kind of flooding that left downtown Jackson underwater in the Great Easter Flood of 1979—while still getting the most use out of the river with development and recreational use—is the stated goal of the Pearl River Vision Foundation.

The group's preferred solution, long in planning stages, is the "One Lake" plan—as opposed to an earlier unworkable "Two Lakes" strategy—and is getting closer to actually happening, foundation spokesman Dallas Quinn explained during an Oct. 13 interview.

"The plan you want to pick is the plan that maximizes the flood-reduction benefits and minimizes any impact to the environment," Quinn said. The idea of One Lake is for engineers to expand the Pearl River outward to both anticipate and then hold increased river levels, all the while mitigating any environmental effects downstream. The plan would also provide waterfront development and recreational property and greater access to the river.

Quinn represents Pearl River Vision Foundation, which local oil magnate John McGowan started to move "One Lake" forward. The foundation is a partner of the Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District, a public entity made up of local mayors and county representatives, to explore flood-control options.

McGowan and his company, McGowan Working Partners, previously had to abandon the controversial Two Lakes project due to varied opposition, including environmental concerns, costs, eminent-domain issues, concerns about conflicts of interest and the potential harm of re-routing the Pearl River on communities downstream as far as Louisiana.

As the scaled-back One Lake option moves forward, communities downstream are still watching with a wary eye.

Lessons of 'Two Lakes'

The ambitious Two Lakes project crashed in 2009, but this time around the proponents of the One Lake strategy aren't taking any chances and have spent a considerable amount of time researching the environmental effects of One Lake and how to mitigate them.

Quinn said the foundation will solicit public opinion after completing environmental studies in the next month or so.

"The main focus right now has been to get the report complete, the draft out for review, back in and fix it, go to the public and then continue on. So I wouldn't say fix it; I'd say make alterations if needed in certain areas," Quinn said.

The report is crucial to wrangling in the estimated $135 million to $150 million in funds the project needs to move forward. The federal government authorized the funds in 2007, but never allocated it as the project hit roadblocks.

The foundation's new study must pass the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' scrutiny, and afterward, an independent engineering firm's verification of its findings, before any federal money touches the project, which Quinn estimates will cost more than $300 million total.

Quinn said that although the project is not fully funded yet, those considerations are much farther down the timeline.

"We are still months away," Quinn said when asked about the report. "There's nothing coming in the next couple of weeks."

Downstream Concerns

Any attempts to contain the Pearl River in this area inevitably will have affects downstream, especially alteration to the free flow of water into the Gulf of Mexico.

"The Pearl has already got one reservoir on it and the cumulative effects, impacts of adding a second dam—a second lake on a river that already has a large dam and lake on it—will be certainly a part of the analysis they have to do," says Andrew Whitehurst, assistant director of Science and Water Policy at the Gulf Restoration Network, and a critic of the Lake projects.

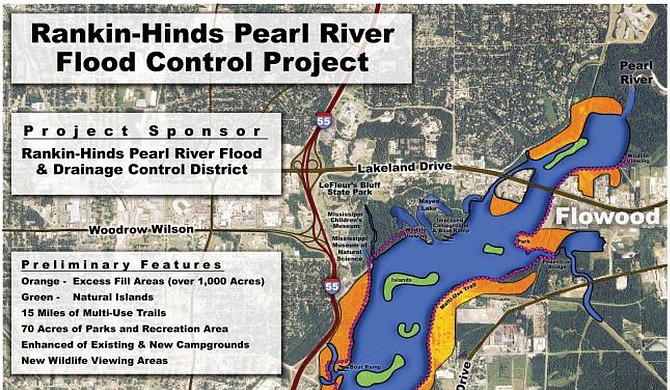

Quinn explained in a follow-up interview on Oct. 17 that the Pearl River Vision Foundation studied several different options for controlling the floodplain in the metro, much of which is concentrated in the area below Lakeland Drive. The Levee Board could choose a "do-nothing" alternative all the way to the foundation's preferred plan: widening the allowed flooding area into a still-flowing wider and deeper river with a weir at the bottom.

A weir is a dam-like installation that allows a constant flow of water over its peak. The foundation's plan would move the weir that exists closer to the Fortification Street exit, four miles downstream. This would pool the water out, after excavation of certain sites, broadening the river. This would also create new accessible riverfront property, a notion that Quinn said was another positive for the project. He did not clarify whether the property would be private or publicly owned and accessed.

Whitehurst pointed to several existing problems, such as riverbanks falling into the Pearl when the water level rises and falls quickly—something that happens when the Ross Barnett Reservoir releases more water than usual.

The engineering department of St. Tammany Parish in Louisiana did a study finding that an additional 1,500-acre lake on the river system could cause an increase in evaporation because the water is no longer moving. That could equal a reduction in the flow of 90 cubic feet per second at the end of the Pearl. This could have tremendous effects in the fragile Delta area, where most ecosystems depend heavily on the presence of brackish water, a mixture of freshwater and saltwater.

"Their concerns include saltwater intrusion, effects on shallow drinking water wells, habitat loss, loss of commercial fisheries and risk to water quality from permit exceedances," Whitehurst said of downstream communities. "So those are the questions about reduced flow at the bottom of the system."

Workable Restoration?

A BP restoration project on the Pearl River located about a mile and half from the mouth, in Hancock County's Heron Bay, includes 40 acres of new marsh, 40 acres of new oyster bottom and three miles of living shoreline. All of that, Whitehurst said, could be in jeopardy from another large body of water upstream.

"In order for that restoration to work, the salinity needs to be moderate. They can't have full-strength seawater coming in at that point," Whitehurst said. "That's one of the problems with the marshes eroding at that point ... salinity has worked against marsh creation, and there is overall marsh edge erosion to the north."

After the Pearl River Vision Foundation finishes its environmental impact and feasibility study, it will hold public meetings, one in Jackson and several downriver. Its past meetings have not engaged the public in dialogue and debate, but asked for written responses.

Whitehurst believes the effects on the environment downstream outweigh any advantages the One Lake project may afford upstream residents. "We don't think that this is good, no. Adding another lake and dam on the river, increasing evaporation and reducing flow? No I don't think that's good for the Pearl, especially in light of the restoration work down the river," Whitehurst said.

Quinn said that the foundation's plan rides the middle line between allowing for increased protection from flooding while preventing any reduction of the flow downriver.

Read the JFP's award-winning coverage of the proposed lakes projects at jfp.ms/pearlriver.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- DA Smith Wins on One Count, But Passes on 'Whistleblower' Bad Check Claims

- Mayor Yarber, Socrates Garrett Address Contracting Dispute, 'Steering'

- UPDATED: Jury Finds Allen Guilty for Cell-phone Payment, Not Guilty on Nine Counts

- Allen Trial: Defense Rests After Making Case DJP Doesn’t Collect 'Taxes’

- DJP Board Attorney Gibbs Takes Stand to Defend Ben Allen's Actions