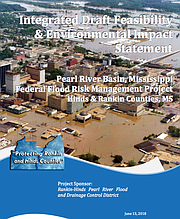

Last month’s flood joins the catastrophes of 1979 and 1983 as one of the largest floods in Jackson’s history, although smaller than both of the earlier ones. Residents, officials and developers alike are clamoring for a permanent solution to the problem of flooding. Photo by Nick Judin

No torrential rains accompanied the Jackson flood of 2020, no howling winds or crackling thunder. In between the soccer field and the Mississippi Basketball and Athletics building on Westbrook Road, the day was nearly serene, crisp and sunny. The road's descent into floodwaters from the overflowing Pearl River was calm, but absolute. A webwork of waterways lay beyond, inundating homes, parks and community buildings.

In his 24-year career, Major Dale Bell had never seen anything like it. Bell commands the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks' Special Response Team, which deployed in February to assist in rescue operations as the Pearl swallowed up neighborhoods in north Jackson. Though it was the first time in his career Bell faced a disaster of this magnitude in the capital city, it may not be the last.

This year's floods, the worst since 1983, have forced a lingering problem back into focus. The current shape and placement of the Pearl River, its two levees and the Jackson metro itself mean that without intervention, the flooding of homes and business will not stop. Now, after decades of acrimonious debate, public officials must decide on the nature of that intervention—and as of now, they're betting on a project called "One Lake, the latest in longtime oilman John McGowan's series of ambitious development and flood-mitigation ideas for the Pearl River through Jackson.

Four Anti-Flooding Options

The Rankin Hinds Pearl River Flood & Drainage Control District—Levee Board, for short—is the State of Mississippi-created agency responsible for crafting a permanent solution to Pearl flooding. The Levee Board consists of the mayors of Jackson, Pearl, Flowood and Richland, and representatives from Rankin and Hinds counties.

The Levee Board says that four flood-mitigation plans are possible. The first is to do nothing. Every expert and official consulted says this is a non-starter. Even the most exorbitant cost estimates for a solution to the Pearl's flooding pale in comparison to letting the problem linger indefinitely.

The second—Alternative A—is the "non-structural" plan. The board considered a variety of non-structural alternatives, but declared them insufficient to address flood control, except for one plan in which the board fully acquires all structures in the "1% chance exceedance flood event flood plain." In plain English, that means areas likely to flood at least once a century. It states removing the structures alone would surpass $2 billion. "The cost of this alternative far exceeds economic justification," Levee Board documents state.

Of Lakes and the Pearl River: A JFP Archive

More than a decade of JFP coverage of flooding and lake plans for the Pearl River

The Levee Board discarded this proposal as quickly as it raised it. But environmentalists like Jill Mastrototaro, policy director at Audubon Mississippi, say the board ignores non-structural and natural options that worked in many other areas.

In an interview, Andrew Whitehurst, water program director at Healthy Gulf, called Alternative A a "strawman," adding, "The non-structural option was made to look like something from Mars that could never happen."

"It was by design to eliminate it as an option," said Louie Miller, director of the Mississippi Sierra Club. Miller decried the entire draft process as overly secret and ultimately biased toward lucrative development. "The first thing you do with a water project is you publish it in the Federal Register. This project is this far along, and has never been published? The EPA hasn't even looked at this project," he said.

Levee expansion is the second alternative. Two levees now run along the banks of the Pearl River, with 13.5 miles of earthen embankments meant to contain water as it tops the banks of the river during flood events. Levees are generally considered to be the most effective means of flood prevention, but they carry significant risks. A levee provides a thin barrier between high floodwaters and inhabited areas, and that means levee failure can be an enormously destructive and deadly event.

Levees can also require manned pumps and additional structures to protect residents in the case of extreme floods, contingencies that drive the costs up. The Levee Board estimates the cost of an effective levee system to be roughly $730 million.

The U.S. Corps of Engineers approved a levee plan in 1996, but a broad field of challengers in Mississippi and Louisiana scuttled the plan due to fears of downstream impacts. Still, levee improvements and alterations will likely play a role in any final plan to address flooding in Jackson, as they do in the One Lake plan itself.

The third alternative would be a combination of "channel improvements," weirs and levees—now the One Lake project, which follows more ambitious and ultimately unworkable lake ideas, including "Two Lakes," abandoned in 2001, as well as the "LeFleur Lakes" plan, which persisted for a decade before Two Lakes.

One Lake means dredging a wide expanse of earth around the Pearl River, creating a lake that skirts the city's eastern border, while removing an existing weir in the river near LeFleur's Bluff State Park and replacing it with one closer to Byram. (A weir is essentially a dam that always allows some water to flow over it.) The idea is to use excavated land to expand the size of presently existing levees, and with the widened channel, even "100-year" flooding would impose less of a threat to buildings in the capital city and some of its suburbs.

One Lake has been the Levee Board's "locally preferred option" since 2012. The Levee Board believes it is an elegant combination of solutions that fit the constricted project area, fully address the flooding dangers; and as part of a sensible cost-benefit balance, create some attractive waterfront property for local developers.

"The conventional thought is that if it were here and in place, instead of having 300 homes that were damaged and flooding, there'd only be 30," Hinds County District 1 Supervisor and Levee Board member Robert Graham said. The board's proposal estimates the total cost of One Lake to be $355 million, including interest accrued during construction. Levee Board attorney Keith Turner previously told The Clarion-Ledger that $134 million of federal funds have been earmarked for the project. The rest of the funding must come from state bonds and local taxes.

The challenges of dredging the Pearl River to create a lake in the Jackson area are daunting, however. The plan can affect water flow, water quality, the riverine ecosystem—some of its dwellers protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act— and the structural integrity of the vital roadways and bridges running along and across the Pearl River, including Interstate 20 and Interstate 55. Sewage and pollution from Jackson's creeks and a number of uncapped waste sites along the project's edge raise questions of health and safety for Jackson's residents along with anyone using the proposed lake for recreation.

"The reason Jackson has such a dynamic flooding situation is because elected officials in Hinds and Rankin county have allowed development on the flood plain that they knew were going to flood," the Sierra Club's Miller said.

Plus, the potential fallout of these changes extends downriver, far beyond the project footprint. The Georgia-Pacific paper mill, the economic lifeline of Monticello, Miss., depends on particular levels of water flow and temperature in the Pearl River. Just last week, the Jackson Free Press obtained documents in which Georgia-Pacific raised serious concerns about the potential effects of the One Lake project, estimating "millions of dollars in terms of capital spend and ongoing expenses," to properly keep the plant running.

The mayor of Monticello, Martha Watts, fears the project could force the plant out of her city. "We can't lose (the paper mill), or we're not here any longer," Watts said in an interview.

One Lake's backers display supreme confidence in the project and routinely downplay the concerns, often with complete certainty. "We're gonna make Jackson the Mecca of the South," Hinds County District 3 Supervisor Credell Calhoun said Feb. 17, before rejecting the possibility that the project could damage the City's bridges.

Still, many of the concerns remain unresolved and, to date, the Levee Board has declined to host a public forum to take questions from the audience openly, instead opting for only accepting written questions and allowing one-on-one conversations.

A partial summary of the most significant questions about One Lake and its potential impacts follows.

Water Quality and Flow

The Issue: Environmentalists and downstream public officials alike have raised alarms over the concern that retaining additional water upstream will change the oxygen level, temperature, or salinity of the water in the Pearl River south of Jackson and in the delta at the Gulf Sound. These changes could disrupt industry—hence Georgia-Pacific's concerns about its mill—as well as change the flow schedule that has an impact on the delicate ecosystem of riverine creatures. Less flow of freshwater to the Gulf Coast could mean creeping saltwater intrusion, which could introduce saltwater predators to the oyster populations in estuarine habitats downstream.

Board Response: The Levee Board maintains that One Lake will not meaningfully affect water flow, quality and salinity for two primary reasons. The first reason, they say, is that the Pearl River above and within the project area provides a limited contribution to the total flow of the river. Second, the weir at the bottom of the project has a gate that allows more water through during low-flow periods.

Turner points to a Tetra Tech study as satisfactory proof that One Lake will not damage the communities or ecosystems downstream, but the Tetra Tech study is one statistical analysis, not a comprehensive opinion. Public officials, environmentalists, and industry sources have requested more studies to better gauge the complex question of flow and water quality. Clarity may come from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' review currently in the works.

Marty Pope, senior service hydrologist at the National Weather Service in Jackson, agreed that the Tetra Tech study presented a simulated model with little downstream changes from implementing One Lake. In low-flow periods, which present the greatest threat to downstream environments, "there needs to be an agreement to keep that flow gate in the weir open," Pope stressed.

Turner said the dam permit would specify minimum flow levels.

Sewage, Trash and Pollution

The Issue: The City of Jackson struggles with sewage runoff directly into the Pearl River. The Environmental Protection Agency placed the City under a consent decree in 2012, which remains in place today. But billions of gallons of "minimally treated sewage" still enter the Pearl River every year.

One Lake would create a large body of water fed by that same Pearl River, providing a broad channel into which sewage would flow and potentially not flush out, creating health hazards for the surrounding communities.

Beyond that, the project footprint includes several polluted waste sites, most notably a former creosote wood treatment facility. The Levee Board's proposal has set aside $8 million for full remediation of these environmental issues, a number a joint letter from environmentalist groups to the Corps called "completely unrealistic." Finally, the project requires the dredging, storage and distribution of tens of millions of cubic yards of sediment from the Pearl River Basin, a massive undertaking with its own potential health risks.

Board Response: The Levee Board rejects the inclusion of some of the pollution sites in the project footprint, suggesting that they lay far enough outside the border of the channel to be irrelevant. Turner did acknowledge the need for better information on proper digging and redistribution of sediment, saying in a February interview that this information is forthcoming.

On the issue of sewage outflow, Turner took a different tack. "We can not build something because you're concerned about the river being polluted, or we can build this flood project and get people's homes out of the flood plain," he said. The issue of sewage flowing into the Pearl River, in his perspective, exists with or without One Lake. "I would hope that by the time we build this thing the City of Jackson will have been able to resolve our sewer problems. But do we not fix people's flooding problems because of that?" Turner asked.

Fix it anyway, Miller said: "At the end of the day, you've got a sewage treatment plant that's been out of compliance for years. There's only one way to clean that up, and that's spending the money."

Bridge Integrity

The Issue: In late 2018, the Mississippi Department of Transportation warned that the dredging required to complete One Lake would cause "catastrophic failure" of the seven main channel bridges that cross the Pearl River in the project area. The threat to public safety and infrastructure would require the complete replacement of nine bridges in total, including spans of Interstate 20 and Interstate 55. The price tag for this replacement tops $100 million. This does not include the logistical challenges of replacing large portions of the Jackson metro's main transportation arteries, forcing mass detours around the project area for an indeterminate period of time.

Despite many One Lake backers saying this issue is resolved and "mediated," MDOT confirmed to the Jackson Free Press on Feb. 20 that it stands by McGrath's letter and had requested additional information from the Levee Board last November, but has yet to receive the requested data.

Board Response: The Levee Board's position is that much less expensive "bridge reinforcements" are all that are necessary to protect the structural integrity of the roadways in One Lake's footprint. The board budgeted $5 million for such improvements in the current plan. Turner acknowledged the MDOT letter in conversations with the Jackson Free Press and said a response to the state agency was forthcoming.

"Our engineers are confident that they'll be able to satisfy the Department of Transportation's concerns on the bridges without replacing them," Turner said in an interview. "Countermeasures will be put in place to reinforce the bridges during the construction." Until MDOT revises its estimation of One Lake's danger to bridge integrity, however, both the costs and the challenges of implementing the project far outstrip the current proposal's estimates.

Conservation Concerns

The Issue: Beyond threats to downstream industry and towns like Monticello and Bogalusa, La., the Levee Board must account for One Lake's potential effects on the intricate, delicate riverine ecosystem of the Pearl River. Dredging and widening the channel as it runs through Jackson changes the nature of the available habitat, destroys huge swaths of bottomland hardwood forests, and alters or eliminates portions of the existing habitats for multiple protected, at-risk species, including the ringed sawback and Pearl map turtle, as well as the Gulf sturgeon.

The fate of these species is not a particular concern to some Levee Board members, including Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba. "It may not be the politically correct thing to say, but I care a lot more about (Jackson residents) than some sturgeon," he said Feb. 17 at a meeting on flash floods in west Jackson, prompted by this reporter asking him about bridge integrity.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service analyzed the One Lake plan in two papers, the latest a January 2020 Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (or FWCA) Report, and came to a number of conclusions. First, in spite of any potential impacts on the individual threatened and endangered species in the One Lake project area, the agency does not anticipate significant danger to those species' overall populations. "The biological opinion does suggest less than a 5% loss (of total population)," Whitehurst said.

But the Healthy Gulf director stressed that ecology represents a bigger picture. "That's the difference between looking at an individual species and the entire river. The wetland loss, the habitat loss, the threats downstream, fall under this larger analysis. It didn't go the drainage district's way," he said referring to the Levee Board.

On the subject of One Lake, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's summary of findings is explicit. "By choosing Alternative C, the channel improvement plan, the District has selected the most environmentally damaging alternative of those analyzed in the draft Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Statement (FS/EIS)," it states.

The report further explains that proposals must meet five criteria to gain the agency's approval, including ecological soundness and all reasonable efforts to reduce ecological impact to the surrounding environs. The USFWS judged the One Lake proposal to violate all five criteria.

Board Response: The Levee Board is quick to point out the relative safety of the endangered species One Lake may affect, and stresses that part of the proposed budget for One Lake includes permanent sanctuaries for the endangered species along the banks of the Pearl River.

But it vociferously objects to USFWS' newest report. "The FWCA Report does not provide the reader an objective review of the Selected Plan," the board's formal response states, suggesting it contains "numerous misrepresentations, incorrect facts, (and) misleading statements."

Most critically, Turner suggests the study fails to consider the board's mitigation plan. "The mitigation plan addresses all the environmental issues," Turner said.

"There are things they've worked on since 2018 that we haven't been able to see. There are external reviews on the plan that are bound to be finished. Let us see them," Whitehurst said.

The full FWCA report and the board's formal response are available on the Jackson Free Press website at jacksonfreepress.com/FWCA.

Alternatives D-Z

The Levee Board has a blueprint for the project and its alternatives—the Integrated Draft Feasibility and Environmental Impact Statement, or DEIS. It discusses five nonstructural options in the draft, but only in passing. The DEIS gives only the full buyout detailed consideration.

The draft rejects everything else, from a limited buyout to structure elevation, to floodproofing, for what it frames as an unacceptable lack of "substantial effective flood risk reduction." The draft claims to consider these plans in concert with other options. But no hybrid proposal of nonstructural options is presented in the draft.

The Lakes Plan That Won't Recede

The JFP's 2010 investigation of the "Two Lakes" plan, including who would benefit.

Audubon Mississippi's examples of successful natural flood-control across the nation include an array of options. Limited buyouts, conveyance improvements and more broadly, wetlands restoration efforts have provided the solution for flood-control projects in multiple regions and environments, along lakes, rivers and coastlines.

Projects like the Meramec Greenway in Missouri used natural restoration, not dredging, to create a cost-effective solution to the Meramec River's flooding. If the Levee Board considered a hybrid wetlands restoration plan, the DEIS does not reflect it.

"We didn't have the luxury then of looking at other hybrid plans. We had to work with what they gave us," Whitehurst said of the public comment period.

The debate over One Lake rages on, as the Corps prepares its final opinion on the project's feasibility. Only the intervention of U.S. Congressman Steve Scalise, R-Louisiana, in America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018, forced the project to have to wait for Corps approval. Prior to that, the Levee Board could have bypassed the Corps.

For Turner, the Levee Board and the project's supporters—some of whom certainly own land that could increase in value once the project was complete—One Lake represents the best possible outcome in exceedingly confined circumstances, both geographic and financial.

For Mastrototaro, Whitehurst, Miller and the unified voices of the project's environmentalist and safety critics, One Lake is a dangerous gamble. They assert that the Levee Board has not fully considered best practices and workable hybrid solutions.

"We want people to get the help they need, but the real help they need," Mastrototaro said in an interview.

Email state reporter Nick Judin at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @nickjudin. Visit jacksonfreepress.com/pearlriver for extensive One Lake coverage.

More like this story

- 'One Lake' Critics Sound Alarms on Bridges, Environment, Industry Effects

- OPINION: Hindsight 2020: Jackson Flooding and 40 years of Failed Solutions

- Coalition Forms Against ‘One Lake’ Proposal

- Conservationists: 'One Lake' Endangers Pearl River

- Mississippi Reservoir Plans Generating Louisiana Concerns

More stories by this author

- Vaccinations Underway As State Grapples With Logistics

- Mississippi Begins Vaccination of 75+ Population, Peaks With 3,255 New Cases of COVID-19

- Parole Reform, Pay Raises and COVID-19: 2021 Legislative Preview

- Last Week’s Record COVID-19 Admissions Challenging Mississippi Hospitals

- Lt. Gov. Hosemann Addresses Budget Cuts, Teacher Pay, and Patriotic Education