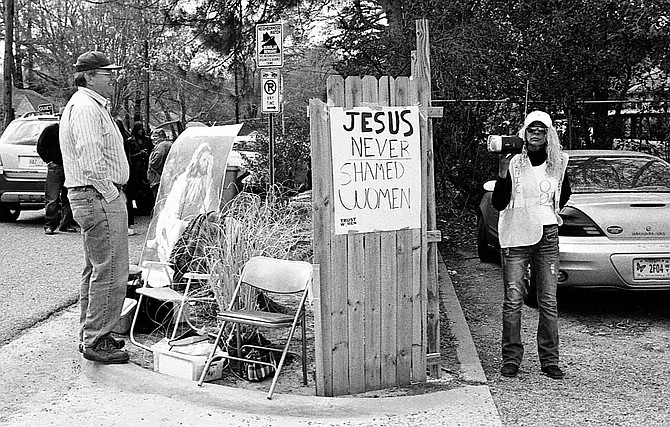

Derenda Hancock began volunteering at the Pink House in 2013. She uses music to help drown out anti-abortion activists. Photo by Ashton Pittman.

JACKSON — "Jesus loves you, mommy. Mommy, please don't kill me," a child's voice pleads from a large speaker system outside Mississippi's last abortion clinic, which is known among its defenders as "The Pink House."

Several times a week, anti-abortion protester Coleman Boyd stands outside the Jackson Women's Health Organization in Fondren and broadcasts recordings of his children's voices for women to hear as they arrive for their appointments.

"What did I do wrong, mommy? Mommy, Jesus loves you. I love you, mommy," a child's voice intones.

"Mommy, I have a heartbeat," yet another says, echoing the anti-abortion movement's most significant political gambit this year.

On April 2, those voices duel with the sounds of Twisted Sister's "We're Not Gonna Take It," courtesy of clinic workers.

Last month, Gov. Phil Bryant signed Senate Bill 2116 into law—making it one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country. Set to take effect July 1, 2019, it bans all abortions after doctors can detect a fetal heartbeat, which typically happens around six weeks gestation—before most women know they are pregnant. It includes no exceptions for rape or incest.

Courts will likely halt the law's implementation, though, after the Center for Reproductive Rights announced a lawsuit on March 28. That has not stopped Mississippi women from fearing they may soon lose their abortion rights, though.

"We get patients who call and say, 'I have an appointment next week. Are you guys closed, or have you stopped doing abortions?'" JWHO Director Shannon Russell Brewer told the Jackson Free Press on April 4. "That's what we get every day. It's the phone calls asking, 'Are you still here?'"

Condemnation and Hellfire

The newest law is not the first time during Bryant's tenure that the JWHO clinic has defended itself against anti-abortion legislation. Last year, a Jackson federal judge struck down a ban on abortions after 15 weeks, but the state is appealing that decision to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. The clinic only does abortions up to 16 weeks.

"They just tried to get a 15-week ban passed, and that didn't work. Now they come back with a six-week ban?" Russell Brewer told the Jackson Free Press. "How much money are you going to waste, governor?"

There may be no limit. On the day Bryant signed the bill, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, a Republican candidate who hopes to succeed Bryant early next year, said he had "absolutely no problem supporting whatever it costs to defend this (legislation) because I care about unborn children."

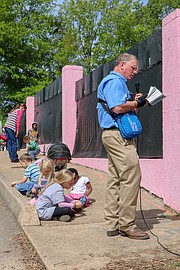

In the weeks since the fetal heartbeat bill passed, the number of protesters who show up outside the clinic has increased, often including Coleman Boyd and his children. Part of that is due to the anti-abortion movement's "40 Days for Life event," which calls on activists to stay gathered around clinics nationwide throughout the Christian holy season of Lent.

For women arriving for abortions, the scene can be chaotic and stressful, as street preachers with megaphones shout condemnation and hellfire toward women they do not know.

"We've had women try and walk up the sidewalk because our parking was full, and had protesters on every side of them yelling ... and they're crying because they're scared," Cory Drake told the Jackson Free Press. "I've had to comfort many women going in. My job is just to make sure they get in there safely without being harassed over and over again."

Drake is a part of a group of volunteers, known as clinic escorts, who are there to counter the chaos outside by helping women make the trip from car to clinic door with as little incident as possible.

The current escort group began in 2013, as the clinic braced for a massive anti-abortion protest on the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that declared safe and legal abortion a right. That year, the clinic was fighting off a separate attempt by Mississippi's Republican leadership to shutter it; Republicans, along with a handful of Democrats, passed a law requiring anyone performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a local hospital—a requirement they knew would be practically impossible for the clinic.

Leaders from national abortion-rights groups like the Feminist Majority and the National Organization for Women met with clinic owner Diane Derzis, and then helped recruit and train clinic escorts.

'Women Belong in this House'

On Jan. 23, 2013, Derenda Hancock, one of those trainees, hula-hooped outside the clinic, her hair blowing in the wind, as she wore a bright yellow clinic escort vest and held up a placard that read, "Celebrate 40 Years of Choice."

In contrast, anti-abortion protesters from the out-of-state anti-abortion group Operation Save America stood nearby, holding placards with graphic depictions of what they claimed were aborted fetuses. Earlier that day, OSA members had carried a tiny white coffin up the steps of the Mississippi Capitol. Inside the coffin, they claimed, were the remains of a 14-week old aborted fetus they had named "Baby Daniel," which they invited adults and children nearby to look at and touch.

Six years later, Hancock is now escort director at the Pink House. Between 2013 and 2016, she said, the ranks of protesters thinned out, and the atmosphere on the sidewalk around the clinic calmed down—until Donald Trump won the 2016 election.

"When Trump got elected, we knew what was getting ready to happen," Hancock said.

With help from Kim Gibson, whom she calls her "right hand guy," Hancock ramped up recruiting efforts, and the group of escorts grew to nearly two dozen. On March 24, just three days after Bryant signed the "heartbeat bill" into law, 20 escorts helped out at the clinic. That day, Hancock estimates, nearly 130 anti-abortion protesters filled the sidewalks outside the Pink House.

Anti-abortion activists Keith and Amber Dalton joined the anti-abortion side that day, along with their children. The couple wore matching black graphic tees, with the outline of a small family home and the words, "Women belong in this House." Underneath that, were the words, "Not this one," situated next to an outline of the White House.

"I've got a few escorts that have been around anywhere from two to four years, but it's very few because this will burn people out pretty easy," Hancock said.

Not all protesters are alike. While many use aggressive shaming tactics, others are quieter. Hancock mentioned a protester named Danny, a Catholic she described as "the calmest protester you'll ever see."

"All he does is come out here Friday and say the rosary," she said. "He never speaks to anyone. So you know, if we've got to have somebody out there, we want Danny because he's very unobtrusive."

'He Reaped What He Sowed'

Many of the protesters, including Coleman Boyd, are affiliated with Operation Save America. Originally called Operation Rescue, OSA has a history of targeted harassment of abortion providers and patients.

In June 2009, Scott Roeder, a man with ties to a Kansas branch that still calls itself Operation Rescue, walked into a Lutheran church in Kansas and shot George Tiller, an abortion-clinic doctor whom the group had long protested, in the head. Tiller, a church usher, was handing out church bulletins when Roeder killed him. After the assassination, Randall Terry, who founded the original Operation Rescue in 1986, held a press conference to say Tiller got what was coming to him.

"George Tiller was a mass murderer and, horrifically, he reaped what he sowed," Terry said at the time.

In recent weeks, the louder protesters have begun spreading their messages to other parts of Jackson. Coleman, who lives in Bolton, Miss., has begun attending city council meetings, where he uses time reserved for public comment to speak out against abortion, which he refers to as "murder." Earlier this month, he used that platform to spread the myth that abortion began in Mississippi as a racist ploy to cut down the black population—a common, but false, narrative anti-abortion leaders use to try to sway African Americans to their side.

Republican leaders, like Bryant and Reeves, often use similarly bombastic language when talking about abortion. Last November, Bryant sought to deflect accusations of racism against U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith by tying abortion to "the genocide of 20 million African American children."

"It is absurd that a governor in a state that has one of the worst maternal and infant mortality rates in the country, where it is one of the most dangerous places for women to give birth—black women to give birth, specifically—would talk about abortion being black genocide," Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund Executive Director Laurie Bertram-Roberts told the Jackson Free Press after his remarks.

'It's Not About the Babies'

On April 4, JWHO Director Shannon Russell Brewer said she does not think politicians like Bryant and Reeves are truly concerned for children. She pointed to GOP leadership's lackluster funding for public education and their decision to slip millions in funding for private school vouchers in the final two days of this year's legislative session.

"It's not about the women. It's not about the babies. It's not about the fetuses," Russell Brewer said. "This is male ego that needs to be stroked badly."

Yet, on the day he signed the six-week ban into law, Bryant declared that "it is the child we are fighting for in Mississippi." Reeves joined him, calling it a "very important day in the history of Mississippi" and made a commitment to Bryant to "continue to fight to make Mississippi the safest place in America for an unborn child."

When the Center for Reproductive Rights filed its lawsuit, Bryant defiantly shot back on Twitter: "We will all answer to the good Lord one day. I will say in this instance, 'I fought for the lives of innocent babies, even under threat of legal action,'" he wrote.

On Bryant and Reeves' watch, though, Mississippi remains the deadliest state in the country for babies after they are born. In 2016, nearly nine out of every 1,000 children born alive in the state died in infancy—a statistic that amounts to nearly 1 percent. That number is up since 2014, when it was 8.2. The national infant mortality rate is 5.6.

Separately, a 2018 report from the United Health Foundation found that Mississippi is the second deadliest state in the country for all children ages 1 through 18, and that mortality rate worsened between 2015 and 2016. The state is the worst in the nation when it comes to clinical health services for children, and the UHF also found that Mississippi is the least healthy state overall for women, infants and children.

During his tenure, Bryant has repeatedly rejected billions of dollars in federal funds to expand Medicaid, which could save rural hospitals in danger of closing and extend health-care access to an additional 300,000 Mississippians.

'A Duty Before God and Man'

The push for heartbeat legislation came after President Trump replaced Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy with Brett Kavanaugh. Whereas Kennedy was known as the swing vote who saved Roe v. Wade from being struck down in the 1990s, Kavanaugh's record on abortion is more conservative. As Mississippi legislators debated the heartbeat bill earlier this year, several Republicans hinted that they believe this abortion ban could fare better in the courts this time around, thanks to the dozens of conservatives jurists Trump has appointed to the federal bench.

This year, heartbeat bills sprang up in state legislatures across the country, and lawmakers in Ohio and Georgia have passed their own since Bryant signed the Mississippi bill in late March.

"We see the Court as being much more favorable to pro-life legislation than it has been in a generation," Ohio Right to Life spokeswoman Jamieson Gordon told NPR on April 12, after the bill's passage there. "So we figured this would be a good time to pursue the heartbeat bill as the next step in our incremental approach to end abortion-on-demand."

Boyd, like others in OSA, disagrees with the heartbeat bills, which he considers too "unjust and wicked" because it does not ban all abortions and punish the women who choose them or the doctors who perform them.

"A heartbeat bill says it is okay to kill babies until you detect a heartbeat," Boyd told the Jackson Free Press on April 16. "That's basically saying you can murder people as long as they don't meet a certain standard of development."

Republican politicians like Bryant and Reeves, Boyd said, use anti-abortion legislation like the heartbeat bills to turn out voters.

"It's a hamster wheel. They say that to keep people running on it to get votes, but nothing's going to happen on it," he said. "That's all political gamesmanship."

In 2011, Mississippi voters rejected the Personhood Amendment, which would have banned abortions, even in cases of rape or incest, and some forms of contraception. In the same election, voters first sent Bryant to the governor's mansion and made Reeves lieutenant governor.

Email city intern reporter Taylor Langele at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @taylor_langele. Jackson Free Press State Reporter Ashton Pittman reports on state politics and campaigns. Follow him on Twitter @ashtonpittman and send tips to [email protected].

More like this story

- Southern ‘Defiance’: The Fight for Roe Rages in Mississippi

- Democrats, Activists 'Infuriated' as Hood Defends Six-Week Abortion Ban

- Mississippi: The Battleground for Roe v. Wade’s Future?

- Mississippi AG Candidate Vows to Defend Six-Week Abortion Ban

- Abortion Debate Epicenter: Mississippi Clinic Stays Open