On a Sunday afternoon at Lumpkin's BBQ on Raymond Road, a predominately African American crowd dressed in formal suits and dresses fill their plates from a buffet line. The restaurant's Sunday dinner features southern staples including fried chicken, beef brisket, ham hocks, collard greens, green beans and cabbage.

A sign on the buffet glass reads: "Eat all that you want, but don't take more than you can eat." The sign is meant to reduce food waste, but it also serves as a caution to patrons whose eyes might be bigger than their stomachs.

With their six children joining them for the lunch rush, owners Monique and Melvin Davis make the Sunday shift a family affair. Melvin works in the kitchen smoking ribs and cooking large pots of vegetables, while Monique refills drinks and greets customers, many of them regulars. The children eagerly help clean up and restock supplies, stopping occasionally to sit and talk with guests.

Originally from Washington, D.C., the Davis family moved to Jackson in 2007 and opened Lumpkin's. With a demanding six-day-a-week work schedule, Monique, 46, admits it can be a challenge to make healthy eating part of her family's routine.

"We were so much more (healthy) before I became an entrepreneur, because I had the time," she says. "It takes time to plan menus, and it takes time to shop. I think a lot of people make unhealthy choices because it's convenient. The problem is, we are killing ourselves with convenience."

Even though food surrounds them, Davis says she wants her family to have a varied diet.

"If you had a steak restaurant, you would get tired of steaks," she says. "I want the children to have diversity in their menu. I want to educate their palates and expose them to different types of food."

When her children were toddlers, Monique's husband worked at Verizon in Washington, D.C., as the family's sole income provider. During that time, Monique made her own baby food; she banned processed food from the house and breast-fed her children.

The family still strives to be as health conscious as possible. Monique and her husband require family sit-down dinners every night, no matter how busy life is. Monique cooks fresh vegetables. Cereal is the only food that can come from a box, and take-out food is not allowed. She is also conscious about what kinds of food she brings into the house.

"The easiest thing as a parent is just to not buy it. It's very difficult for me to control it once it's in the house; once I bring it home, it's a free-for-all. I'm only one person. I can't see six people all the time," she says.

In a part of town where fast-food chains are more common than grocery stores, Monique knows that Lumpkin's is one of the few places where residents can get their fill of fresh vegetables. At $8 for weekday lunch buffet, Monique says she wanted to make sure the meals are affordable for the community.

Monique also admits that it's hard to prepare food as healthy as she'd like to, because southerners are accustomed to sweet, fatty foods.

"We had to sweeten our barbecue sauce when we got here because people just didn't like it; they said it wasn't sweet enough," Monique says. "Now we are incrementally changing it back to a level we feel comfortable with. But in order to survive, we had to change our menu offerings to what people are going to eat."

Davis says that as a west Jackson resident it can be difficult to find fresh produce in her neighborhood. Recently, the Brookshires Grocery on Terry Road closed, and Sesame Seed, a supplemental health-food store, moved to Clinton.

"There is a lack of fresh quality produce in this part of town," Davis says."[T]o rebuild Jackson as a total city is to equally distribute quality food and grocery stores."

Monique says the correlation between obesity and race dates back to when slaves had to prepare food to added calories and nutrients to the scant amounts of food provided to them. For example, sugar was often added to foods that had rotted to make them palatable, and vegetables were often overcooked so that slaves could gain nourishment from the water the vegetables were boiled in after serving their masters. Overcooking vegetables might contribute to a better taste, but doing so depletes vital nutrients.

"People are accustomed to overcooking their vegetables, and we are trying to change their palates. They aren't accustomed to eating vegetables that have a crunch to them," she says.

"The technique that was used for our survival is now killing us because we don't know how to prepare our food."

Exercise is another priority for the Davis family, despite time constraints. When Monique became pregnant with her sixth child at 42, she started taking belly-dancing lessons as a way to stay fit, knowing that she was considered high-risk because of her age.

Saturday mornings, Monique and her 9-year-old daughter, Ava, clear tables and chairs from the dining room at Lumpkin's and instruct belly-dance classes. Monique says she started the classes as a way to provide access to affordable fitness classes for the community, with each class costing only $5. Currently, she has about 25 students and hopes to open a studio in Jackson in the next year.

"It's a good way for women to get in shape, and women here—especially African American women—need access to that," she says.

National Spotlight

On a sunny afternoon in March, Brinkley Middle School students wearing "Let's Move" T-shirts and waving handmade signs cheered wildly inside the school auditorium as first lady Michelle Obama walked on stage.

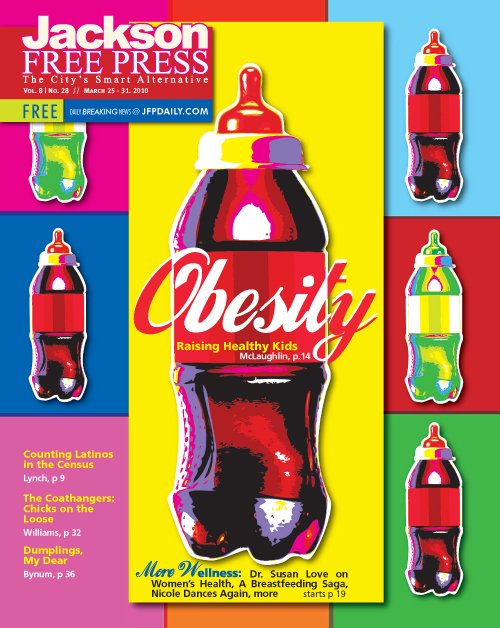

Obama visited Jackson March 3 as part of her "Let's Move" campaign to promote health and exercise to combat a national obesity epidemic. She started the campaign last month with the goal of ending childhood obesity in the next generation. The national obesity rate has tripled in the past 30 years with 30 percent of American children now obese.

Mississippi currently ranks No. 1 in the nation for obese adults and children, according to the Centers for Disease Control, with 44 percent of children and 32.5 percent of adults overweight or obese. Additionally, African Americans have a 51 percent higher prevalence of obesity that whites nationwide. Doctors have linked obesity to increased risks for a variety of conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, arthritis and heart disease—all of which ends up costing the state approximately $750 million per year.

The goals of "Let's Move" are to support parents, provide healthier food in schools, promote physical fitness, and make healthy and affordable food available in every part of the country through policy initiatives and education.

Speaking March 17 to representatives from companies like Coca-Cola, General Mills and Kraft Foods, Obama called for more accountability in marketing healthier foods to children during a meeting of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. The next day PepsiCo announced that it would pull full-calorie soft drinks from primary and secondary schools by 2012.

Currently, the Food and Drug Administration is researching consumers and the food industry to adopt new nutritional information for the front of food packaging.

Despite the state's poor health record, Obama highlighted Jackson Public Schools' efforts to tackle the issue. "I am not here to highlight what's wrong; I am here to highlight what's right," she said during her address to students.

Obama also visited Pecan Park Elementary School. Both schools have implemented creative solutions to end obesity. Pecan Park has received several grants to create infrastructure and programs to encourage physical fitness for children. In 2006, with a grant from Home Depot, parents and students at Pecan Park built a playground for students. In 2007 a grant from Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Mississippi funded a walking trail.

Mary Hill, 53, has served as the district's food service director for the past 27 years. Last year, Hill secured funding from grants and the federal stimulus program to replace several schools' deep fryers with ovens. She also secured funding from the United States Department of Agriculture Fruit and Vegetable Program, which makes fruit and vegetables available at no cost to students. The program not only ensures fresh fruit for school snacks, but also sends home fruit with the children.

Hill says that one of the biggest challenges is making sure that healthy-eating and fitness habits translate to the children's home life.

"Many of our children still have eating habits that aren't desirable for good health," she says. "Sometimes it's hard to get them to eat carrots or fruit. It's a cultural change that has to take place for everyone to be on the same page."

Change From the Top Down

Beneta Burt's desk sits in the center of what was once the New Deal Supermarket on Livingston Road. A partition divides the building: One side is an indoor farmer's market, and the other is filled with medicine balls and mats for community exercise classes. Burt has worked in many formal office settings, including a stint in the late 1980s when she worked for former Gov. Ray Mabus.

Burt, 60, is the project director and principal investigator for the Jackson Roadmap to Health Equity Project. She eagerly gives a tour of the space that has become central in the city's efforts to fight obesity. At the front of the building, tiered Styrofoam pots connected by PVC pipes contain romaine lettuce, strawberries, bell pepper and tomato plants. The plants sit in front of tall glass windows as the afternoon sunlight streams in. Burt has created a hydroponic garden—similar to a greenhouse—in hopes of teaching the community how to grow their own food.

"I was thinking about how we could do something to help sustain our work," Burt says. "We want everything we try to do to increase the status of health in the community, and anyone can do this—it's a simple system."

Funded by a $1.5 million grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Jackson Roadmap to Health Equity Project started in 2006 as a community initiative to combat obesity.

In 2000 a group of representatives from the University of North Carolina, W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Jackson State University held a discussion addressing one central question: Why do African Americans get sick and die sooner than other groups of people?

The discussion focused on Mississippi and the correlation between poverty and obesity rates and that conversation was the catalyst for a community steering committee that created goals and strategies to improve health for lower-income and predominately African American communities in Jackson.

"The idea was to talk to the community as opposed to people coming and thinking for the community," Burt says. "[T]he goal is to institutionally change things that affect people's health—not just do a program that lasts for a minute, but something that can institutionally change how communities operate."

Ultimately, the steering committee formed Roadmap to Health to make a systemic change in local schools. The steering committee chose to focus efforts at Johnson Elementary School, Brinkley Middle School and Lanier High School because they feed into one another.

The steering committee then decided to change eating habits from the top down, starting with the food services workers who are responsible for feeding students.

"We have food-service workers who cook for kids nine months out of the year, and if they aren't healthy, that probably isn't going to translate to good health for our children," Burt says. "That's when we started to approach our project schools and ask the food-service workers how they felt about their own health, if they thought the community was healthy, and how they felt about improving their own health status."

Burt discovered that the majority of the workers felt poorly about their health and lifestyle habits, but many worked two full-time jobs and could not afford a gym or the time to exercise. The project organizers decided to bring personal trainers to the schools and provide fitness classes at the Roadmap building during the summer, free of charge. The training program was also extended to students in the project schools.

"Inability to pay should not be a reason for people not to have good health," Burt says.

Once the training sessions started, Burt says the food-service workers reported having more energy and feeling better overall, which trickled down to the students. "The folks who now prepare the students food are role models to them," Burt says. "Now when kids go through the food-service area in the morning, they see their food workers working out. And now when students go through the cafeteria line, food-service workers, who now look good, can say to a kid in a legitimate way, 'Why don't you have a salad today?'"

Ernest Jackson is one of the personal trainers who works with the food-service staff and students at the project schools. A former YMCA manager, Jackson says food-service workers look forward to his visits every morning.

"Those women are die-hard health freaks now," Jackson says. "If I'm five minutes late, they are already warming up and ready to go."

Jackson also trains students at Johnson Elementary and Brinkley Middle School three days a week for an hour at a time. The training is meant to supplement the physical education requirement for public schools, but Jackson says that recess and PE are often the first things cut when schools need more time to improve test scores.

Filling a Gap

Last July, Roadmap to Health started an indoor farmer's market with a cooperative of Mississippi farmers, to address the lack of produce and grocery stores in the neighborhoods surrounding the Jackson Medical Mall.

The market not only provides fresh vegetables; Burt and other volunteers give patrons healthy recipes and preparation tips. To ensure that the produce is affordable, Roadmap buys the produce at cost from the farmers and then sells it at a reduced rate to the community.

Burt says that farmer's market was never in the original plan for the project, but once trainers started working with students and food service workers, it became apparent that there was a need for affordable produce. Since the Jackson Medical Mall rents space to Roadmap to Health, Burt says having a fitness and healthy food facility fit in perfectly with the medical mall's mission of providing wellness, economic development and affordable health care to the community.

"In this neighborhood, we have folks coming in telling us how grateful they are that we are here, because they no longer have to pay people to take them long distances to buy fruits and vegetables," Burt says.

The market opens this year April 30, and Burt hopes to extend the market's season year round.

Plans for a Save-A-Lot grocery store to break ground at the Jackson Medical Mall is also underway, and Burt says she hopes to collaborate with the new grocery store to provide residents with more opportunities to purchase healthy food. The grocery store will open this summer.

"There is a synergy that we can develop with Save-A-Lot and the farmer's market. That's the kind of partnership we want," Burt says. "I can see us referring people from the farmer's market to the store, because we know this is a store that is interested in the health of the community."

The project's grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation officially ended in January, but the foundation has continued to fund the project on a month-to-month basis. In addition to looking for additional sources of funding, Burt is also implementing strategies for the project to sustain itself. Plans for a greenhouse and a recycling center are in the works. The greenhouse, which will be located on the grounds of the Medical Mall, will be used to grow large quantities of food year round for the farmer's market. Burt is planning to employ members of the community to work in the greenhouse and will start a floral business to fund the project.

This summer, Roadmap will host "Food and Fitness," a program for girls in grades six through eight. Dieticians and fitness trainers will educate the girls about healthy eating and fitness while allowing them to develop their own business models and sell food to their peers and families.

"Hopefully, by the end of the summer, the girls will have better sense of themselves and higher self esteem," Burt says. "They will also have a whole summer of changing their lifestyle because they will have worked in the market all summer long and eaten healthy foods."

Burt knows that it takes collaboration and partnerships to change values and lifestyles in a community. She spends a large portion of her day meeting with other health advocates and looking for ways to expand Roadmap to Health services. She wants to increase opportunities for fresh produce in south and west Jackson, for example.

Currently, Duvall Decker Architects is working on a master plan for west Jackson that will include research about the access to grocery stores in west Jackson, and the nonprofit My Brother's Keeper recently received a $360,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to increase farmer's markets and affordable produce to all of Jackson.

While the fight to end obesity involves changing cultural ideas and institutions, Burt says you have to look at the root causes of the problem and start there.

"I wouldn't say eating junk food is cultural; I would say that people eat what's available to them. People of very low economic means have had to eat what their families can afford. Often times that means not having the most healthy foods available," she says. "[Y]ou have families that are so strapped with other obligations that it's easier to run to a fast-food store. But other times, it's not knowing what's considered healthy."

For more stories related health, be sure to visit our BodySoul blog, and also visit our Health & Wellness Event Listing to view up coming health events or post your own.