From local lawyer donations to outside groups running ads, donors spent over $1.5 million on the District 1, Position 3 Mississippi Supreme Court Race between Justice Jim Kitchens (left) and Judge Kenny Griffis (right). Photo by Imani Khayyam.

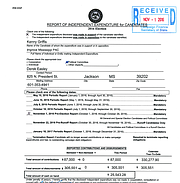

JACKSON — The "dark money" that poured into the state in order to defeat incumbent Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Jim Kitchens did not pay off this election cycle, as he defeated his challenger Kenny Griffis by 25,000 votes. The two candidates raised about the same amount of money for the race, but state business PACs and outside organizations doubled Griffis' financial support with another half-million dollars. Mississippi donors, political action committees and outside groups spent more than $1.5 million on the race.

A separate PAC, Improve Mississippi PAC, and at least two outside groups spent more than $500,000 running attack ads against Kitchens or campaigning for Griffis, a Mississippi Court of Appeals judge with six years left of his term. The money from groups outside the state cannot be traced to their origin due to the Citizens United v. FEC ruling in 2010, in which the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the ban on independent expenditures in elections for corporations and unions.

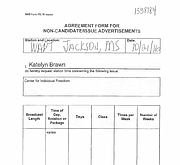

The Center for Individual Freedom, a Virginia-based "constitutional advocacy organization," spent more than $175,000 running attack ads against Kitchens throughout the election, Federal Communications Commission records from WAPT, WLBT and WJTV show. Its ads attacked Kitchens for "not keeping kids safe" and "using a legal loophole" to let criminals off. On the night of his re-election, Kitchens addressed the ads and what ended up being a race filled with dark money.

"These entities don't care about criminal law unless someone is stealing from them, so they take something like that (court cases mentioned in the ads) and try to influence an election by deception or half-truths or worse," Kitchens told the Jackson Free Press.

"And the people of Mississippi, I think, are tired of it; we've seen this in several judicial elections."

Citizens United Loophole

The Improve Mississippi PAC, called IMPAC for short, started as a coalition of Mississippi PACs, donating large amounts of money (from $10,000 to 50,000 each) to IMPAC. Mississippi law caps judicial election contributions at $5,000. An easy way to go around that law is to create a separate PAC or get money from outside donors in order to give more money.

Matthew Menendez, counsel at the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, says judicial elections used to be low-profile and low-spending races back in the early 2000s, but both corporate interests and plaintiff attorneys have started spending more in recent years.

Most of Kitchens' $586,000 came from attorneys, from inside and outside the state.

"I think all of my money was from inside the state of Mississippi, and I have friends outside the state that contributed. But they're people I know, people that I've worked with as an attorney for many, many years outside the state who've been loyal to me, and I'm grateful for that," Kitchens said on election night.

Menendez said contributions from lawyers usually mean they are looking for good favor in the outcome of pending cases or future cases.

"What we've seen in judicial elections in particular is massive spending in contributions from lawyers. It's sobering to think about the interests of the people trying to elect these judges," he said.

Kitchens said in an interview before the election that he signs his campaign-finance reports blindly, not looking at who has donated so it cannot affect his decision-making on the bench.

Other judicial spending from outside interest groups, Menendez says, is common, especially in the wake of the 2010 Citizens United decision. The biggest issue to that decision is that of "dark money."

"Citizens United has not made anything better. It removed any limits on outside spending in elections including in judicial elections," Menendez said. "A lot of that money is what we call dark money, from groups that don't disclose their donors."

The Center for Individual Freedom, for example, is a nonprofit organization, so data on donors would be limited to anything in IRS documents. The National Association of Realtors Fund spent $75,000 in support of Griffis, filings with the secretary of state's office show. There are no records of what this money was spent on, although a captured screenshot shows that at least some of that money must have gone toward Google ads that pop up on various sites. The National Association of Realtors is a membership organization for real estate agents throughout the country that members who pay dues.

Law: Ignored or Unknown?

State election law mandates that judicial elections be nonpartisan in nature, which means no judge can affiliate with a particular party.

Further limitations exist in state law, but federal courts have long since struck down such provisions.

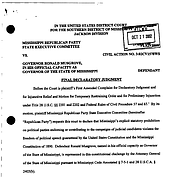

For example, state law technically prohibits political parties and committees affiliated with political parties to fundraise, contribute money to or endorse judicial candidates. A 2002 federal court case, Mississippi Republican Party State Executive Committee v. Gov. Ronnie Musgrove, changed that law, however.

In his declaratory judgment, U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate wrote that the limitations in Mississippi state law "unquestionably limit the core political speech of the parties and fundamentally impair their First Amendment rights, without being narrowly tailored to a compelling government interest."

Wingate threw out the part of Mississippi law that said political parties and committees cannot contribute, fundraise or endorse candidates for judicial office on the grounds that several federal courts had ruled that such restrictions violate a party's First Amendment free-speech rights.

Darlene Ballard, the executive director of the Mississippi Commission on Judicial Performance, said she is working with the secretary of state's office to propose legislation to clean up Mississippi's statutes to come in line with how the courts ruled back in 2002.

In this past judicial election cycle, the Mississippi GOP not only endorsed Griffis and two other judges in the 2016 election cycle but also publicly campaigned with those candidates throughout the state.

Judge Wingate's 2002 ruling made that legal, so any political party who wants to fundraise for or endorse a candidate for office in Mississippi is welcome to do so. Wingate's judgment did uphold the limits on monetary contributions to judicial candidates, however.

Courts in other states have found that laws like Mississippi's that bar political parties from being involved in judicial races to be unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The Republican Party of Minnesota v. White U.S. Supreme Court case allowed judges to speak out on some issues (for example, to say they're pro-life or pro-choice) as long as they stop short of pledging to reach a particular result, Menendez said. Spending in judicial races is not limited to Republican-leaning states. Menendez said 2016 was another record-breaking spending cycle for judicial races around the country.

"We're seeing records being broken all over the place," Menendez said. "The best way to think about it is there was a problem before, and then Citizens United was like pouring gasoline on that fire."

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus