College costs are soaring, and Mississippi students remain grounded. New information from account-management service Manilla.com, a subsidiary of media conglomerate Hearst Corp., shows that Jackson is among the cities with the highest average student-loan debt. The report, published in late October, ranks Jackson No. 8, with an average college-loan indebtedness of $16,540.99.

Memphis ranks No. 1 on the list, with student borrowers having $19,507.37 in college debt. This news comes on the back of more troubling news about the affordability of college. Just before the federal government went into partial shutdown mode amid a dispute over the government's ability to borrow money, the U.S. Department of Education released the latest data on the three-year federal student-loan cohort default rate, which measures the percentage of borrowers who default on their federal student loans.

Those numbers are on the rise, going from 13.4 percent in fiscal year 2009 to 14.7 percent in FY 2010, the report shows.

Whitney Barkley, a staff attorney with the Mississippi Center for Justice, said that with all that debt piling up, the college-loan bubble could be "the next big crash," possibly surpassing the mortgage meltdown that ushered in the Great Recession.

"Borrowers (of today) can't contribute to the economy the way that previous generations contributed to the economy," Barkley said.

A glint of good news for Mississippi lies in those grim numbers, however.

Here, about 55 percent of students graduate with loan debt compared to the national rate of approximately 75 percent. That's due, in part, to Mississippi's strong community college system, which helps keep student-loan default rates down, Barkley said.

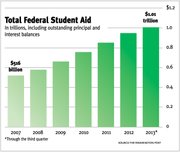

Nationwide, the problem is daunting. At $1.3 trillion, outstanding student-loan debt is second only to mortgage debt in the United States. In Mississippi, the average graduate leaves college with roughly $24,000 in loan debt, which is also lower than the national average of $26,600.

Fueling the bubble is a big jump in college tuition costs at public universities, which have risen 50 percent since 2000 and, because of the economic slump, more people went back to school to learn new skills. During this period, for-profit, or proprietary, schools expanded their presence in the college marketplace. Barkley noted that for-profit institutions are typically more expensive than traditional two- and four-year colleges.

"The growing number of students who have defaulted on their federal student loans is troubling," said U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan through a press release about the student-loan rates.

"We remain committed to building a shared partnership with states, local governments, institutions, and students--as well as the business, labor, and philanthropic leaders--to improve college affordability for millions of students and families."

Help from Washington?

Over the summer, President Barack Obama went on the stump to promote his plan to make college affordable.

"[S]tudents and families and taxpayers cannot just keep subsidizing college costs that keep going up and up," Obama said in his Aug. 24 weekly address from the White House.

The reasons for the increases in tuition are numerous, but chief among them are that states have cut funding for their schools in reaction to the latest economic downturn. In Mississippi, state funding has decreased by nearly a third from 2008 to 2013, which comes out to a cut of $3,146 per student.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, warns that those cuts do not bode well for the future if states do not begin to re-invest in higher education. "[S]tates that enact deep tax cuts will make it much more difficult to rebuild their higher-education systems and jeopardize their ability to compete for the jobs of the future," the CBPP stated in a March report.

Donations are also down, too, especially for private colleges. Costs, on the other hand, despite some draconian budget cuts, have still crept up. In the end, schools have passed on their shortfalls to students.

The first tine of the president's three-pronged plan involves setting up a value rating system to rank colleges. He has directed the U.S. Department of Education to come up with the system based on metrics such as whether schools provide access to low- and middle-income students, tuition costs, average student-loan debt at graduation and whether those graduates get well-paying jobs after they leave the halls of academia.

The second part of the president's proposal is "The Race to the Top: College Affordability and Completion" challenge, which will reward states "that are willing to systematically change their higher education policies and practices," to "increase the number of college graduates and contain the cost of tuition," the White House website states. The last part of the plan proposes to cap student-loan payments at 10 percent of earnings.

Although the details are far from clear, yet, the first part of the president's proposal is already generating criticism, and it has some college administrators worried. M. Christopher Brown, president of Alcorn State University in Lorman, believes that in Mississippi, where tuition at public universities is lower than anywhere in the country, a high-value ranking could artificially keep Alcorn's tuition so low that it could interfere with his school's ability to function.

Ranking colleges to determine eligibility for funding is nothing new. In a nationwide analysis published on its website in February, the National Conference of State Legislators showed that a dozen states had already mandated performance metrics to determine the amount of funding state colleges and universities receive from state coffers. The metrics include course completion rates, time to graduation and the numbers of low-income and minority students.

At the time of the NCSL analysis, most states had either implemented performance funding, were transitioning to it or were talking about it.

The analysis showed Mississippi being "in formal discussions" to hop on the performance-funding bandwagon. Lawmakers made it official before this year's legislative session ended in March.

Hank M. Bounds, Mississippi's commissioner of higher education, responded to a Jackson Free Press interview request regarding the president's plan with the following email:

"Mississippi public universities provide a great value and return on investment for our students and our state. I am confident that they will do well if the proposed rating system is put into place.

"The new allocation model approved by the Board of Trustees in April is a performance-based model that already drives improvement in student retention and graduation rates.

"Mississippi has the lowest per capita income in the country, so our universities understand the issues of accessibility and affordability and work hard every day to open doors of opportunity to all of our students."