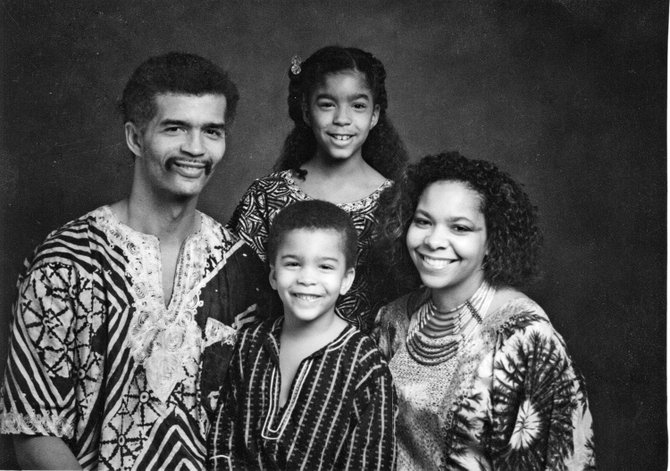

Pictured here with his children, Rukia (center, top) and Chokwe (center, bottom) and wife, Nubia (right), who died in 2003, Lumumba is intensely involved with the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM), which promotes universal human rights. A part of the MXGM called the Jackson Plan seeks to develop young Jacksonians into leaders. Photo by Courtesy Chokwe Lumumba

In September 1955, a young Edwin Taliaferro saw an image that would shape his thinking over the next five decades. The photograph, published in Jet Magazine, was of Emmett Till's mangled 14-year-old face in an open coffin.

Chokwe Lumumba, as he is now called, describes Mamie Till's decision to allow her son's visage, ruined by vindictive racists in Mississippi, to be splashed on the national magazine's cover an act of bravery, the event that first pricked his political consciousness. But it was the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. 13 years later that became Lumumba's entree to human-rights activism.

To hear that Lumumba adheres to the teachings of King, a Baptist pastor who preached non-violence, might surprise followers of Lumumba's career, which now includes a run for Jackson mayor.

However, Lumumba believes King's philosophy of eradicating "infectious discrimination, racism and apartheid" is perfectly in sync with his own way of thinking, which the first-term councilman would bring to the mayor's office.

"My development was always making the world better. I was always sensitive to any kind of repression. My thing was fairness, and I was offended by unfairness," Lumumba told the Jackson Free Press recently.

Lumumba, 65, is hypersensitive to the fact that he is, in the imaginations of many people, an anti-white bigot salivating at the opportunity to expel all of Jackson's non-pigmented people and seize their property for redistribution to the city's black majority.

"We're not looking for a bloody revolution in the city of Jackson. We don't want to offend anyone else's rights. However many white people there are in Jackson, they have to be treated by the highest levels of human standards as anybody else, because if we don't do that, not only do we offend Martin Luther King's philosophy, what we do is betray our own revolution.

"Our revolution is for the better idea; it's not just for the change in colors. So it's not a question of whether in a predominantly black jurisdiction that you've got to oppress white people. Where that notion comes from, I don't really know."

Chokwe Lumumba: From Militancy to Mainstream

The 2013 JFP Interview with Chokwe Lumumba delves deeply into his past, and his world view.

Part of the perception stems from Lumumba's radical roots that include his cofounding the New Afrikan People's Organization, which wanted black people to have their own nation, called the Republic of New Afrika, in the southeastern United States. In August 1971, police and agents from the FBI raided the house used for RNA's headquarters in west Jackson. Police lieutenant Louis Skinner died in the melee, and another police officer and a bureau agent were wounded. Lumumba was not involved in the shootout that resulted in the arrests of 11 New Afrika members including its president, Imari Obadele.

"The Republic of New Afrika has been miscast as the black flip side to the Ku Klux Klan when, in reality, the Declaration of Independence prohibited color, class and gender discrimination," Lumumba said.

"What they were was ahead of their times, especially in terms of no gender discrimination because a lot of people in the movement at the time were still practicing gender discrimination. So what the RNA was saying was that in states like Mississippi (that) had dead, cold frozen black out of the system, then blacks have a right under international law to ask for a plebiscite, a freedom vote, on what they want their destiny to be."

For Jackson, which has the second highest concentration of African Americans of any city larger than 150,000 residents in the U.S., Lumumba wants that destiny to ensure that businesses operating in the city hire residents, 80 percent of whom are black.

That part of his political development stems from a strain of Black Power ideology that Stokely Carmichael and the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee espoused. It focuses on political and economic self-determination for African Americans.

"SNCC had resolved that they would take a more affirmative fight for power. It wasn't just going to be access. In other words, not just being able to sit at the counter. They wanted to own the store, and they wanted blacks to have that opportunity to own the store," Lumumba said.

Lumumba's reputation as an activist earned him a laundry list of high-profile and sometimes controversial clients including Fulani Sunni Ali, indicted in the 1980 Brinks armored-car robbery for whom Lumumba secured an acquittal; the irascible Tupac Shakur; Lance Parker, who was accused of trying to shoot the fuel tank on Reginald Denny's 18-wheeler during the Los Angeles riots; and Mississippi's Scott Sisters. Likewise, his activist training has sometimes landed him in hot water with judges and the legal community.

In 2005, the Mississippi Bar Association suspended Lumumba's law license for six months for saying in court that a Leake County circuit judge possessed "the judicial demeanor of a barbarian."

Lumumba cites the anti-racial-profiling ordinance he championed on the city council in 2010 as evidence that he wants all Jackson residents to create a new blend of people.

"It's a new idea, a new way, a new justice frontier. We have not only a black culture, we have white people who have their culture; we have Hispanics, we have Asians," he said.

"And something's go-ing to happen as a result of that. The question is: Is it going to be something good or something bad? What we need is a new culture with new ideas that leads up to becoming a model city in the world."