June 27, 2012

In August 1987, Louisiana State University geologists reported that a rock formation called Tuscaloosa Marine Shale could contain as much as 7 billion barrels of oil. Writing in LSU's Basin Research Institute Bulletin, researchers reported the shale play could contain "a potentially significant commercial oil reservoir" underneath the Mississippi-Louisiana boundary including southwestern counties in Mississippi westward through central Louisiana to the Texas border.

At the time, the fact that so much precious crude was locked away in dense shale seemed moot. There was no practical method to go about getting it out of the ground. But fast forward to the present day, and the combination of an oil-friendly political climate and new extraction technologies—namely, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking"—might put the TMS in play.

"I categorize this play as an emerging play," said Kirk Barrell, president of Amelia Resources, a The Woodlands, Texas-based exploration and production company. "It's still economically unproven."

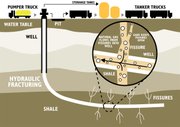

Fracking has spurred booms in other parts of the country while also generating controversy. The process involves injecting high-pressure water, sand and toxic chemicals deep into the group to break apart dense rock formations to release gas and oil trapped between the layers. Environmental and public health concerns that fracking raised prompted the U.S. Environmental protection agency to release rules in April that limit air pollution emitted during the drilling process.

Despite the concerns, Marcellus Shale has brought thousands of jobs to the eastern U.S. and millions of dollars in investment. North Dakota and areas of Montana had similar experiences with the Bakken formation's estimated 18 billion barrels of reserves.

Because TMS is a relatively new play, oil companies need to conduct more testing before they can really assess its full potential. Early signs are encouraging, Barrell said, but drillers will have to find ways to tamp down drilling costs before they start making real profit.

Major players in other oil-shale plays all have substantial acreage positions in southwest Mississippi, including Encanca, Devon Energy, Goodrich, EOG Resources and Indigo Minerals. These companies have been busy getting leases for mineral rights from Mississippi residents in Amite and Wilkinson counties.

But sorting through Mississippi's complex mineral-leasing laws has proved a challenge for many landowners. An online forum for mineral-rights owners in Amite County is full of people who are confused, at best, and at worst, highly skeptical of the oil companies.

"We need to get a group together and hire a lawyer," writes one woman on the Amite County Oil and Gas Discussion forum. "This is far too complicated for us."

Another man, who describes himself as 80 years old and in poor health, said mineral-rights owners are "being jerked around" by landmen. In the parlance of the minerals business, landmen are intermediaries the oil companies hire by the day to track down people who hold mineral rights and negotiate a deal to lease the rights for the companies.

Typically, the companies pay an upfront "bonus payment" to lease minerals for three years, and most agreements include the option to extend the lease for two years. In addition, mineral owners receive a royalty for the oil or gas pumped out of their property, usually about 20 percent of revenues from the well.

Barrell suggests that landowners consult an attorney before they sign a deal with anyone for their mineral rights. Walking people through the process, he said, is not the oil company's job.

"They're making an offer for a financial transaction, so it's not really their obligation to educate the landowner," he said.

Dan Turner, spokesman for the Mississippi Development Authority, said the agency held an informational meeting with officials in Liberty about what the oil boom could mean for development in the county in direct and ancillary investments.

"People who come in work in the oil and gas industry have to find some place to eat and stay," Turner said. "If this turns out to be everything we hope it is ... it could be a real economic jolt."

Comment and email R.L. Nave at [email protected].