Back in 2001, drivers heading down Highway 220 on cold weekday mornings could see plumes of heat billowing out of the exhaust towers of KGen's Jackson power plant on Beasley Road.

The facility came online that year with little fanfare, but it was unusual in a state that has seen scant growth in power generation. The plant is one of the most efficient, natural-gas electric generators in the Southeast, expelling some of the cleanest exhaust that can be expected from a fossil fuel-based power plant. It exists to sell power to Entergy.

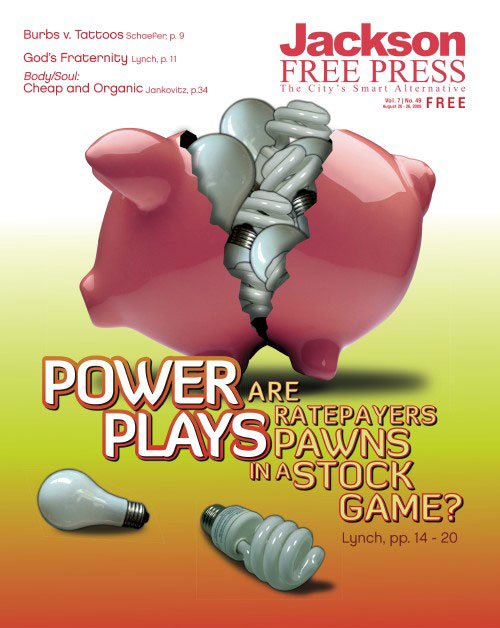

However, now the facility operates only 10 to 20 percent of the year, if lucky. If used more, the plant could ultimately counter a future of exploding electricity bills in Mississippi.

The plant exists to sell power to Entergy, which appears to have little desire to use ita situation KGen management possibly hoped they could overcome when they purchased the facility from an affiliate of MatlinPatterson Global Advisors LLC, in 2007.

KGen officials would not comment for this story, but the company's Web site attempts to explain away the fallow facility's poor yield, saying that plant production varies with weather conditions, and that "four of (KGen's) plants currently operate on a merchant basis without long-term purchase agreements, and therefore are exposed to significant volatility in prices and generation demand."

But that's not the whole story. Entergy spurns power from independent producers like KGen in favor of electricity from its own Rex Brown generator near Livingston Road. Rex Brown, named after a Mississippi Power & Light president who served until 1954, is a 60-year-old antique burning natural gas and oil at peak capacity for much of the year, but only at about 60 percent efficiency, compared to more modern plants.

The Rex Brown plant is entirely Entergy-owned, however, perhaps providing incentive enough for its continued use even if it means ratepayers have to make up the difference.

The Lost Revolution

The story of the unused power plant, and related concerns about consumers' inflated electricity bills, begins with the Energy Policy Act of 1992 and two landmark orders made in 1996 by the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commissionintended by Congress to play key roles in opening the U.S. energy market to competition. For 100 years, states encouraged a regulated monopoly system to supply electricity under the argument that a heavily regulated one-producer system created less havoc in building transmission lines and also seemed to lower electricity prices.

FERC Order 888 came along and mandated the "unbundling" of electrical services. "Bundled" means that the money customers pay power companies for electrical service includes everything involved in the production, transmission and distribution of that service. It also called for the opening of transmission lines to smaller competitors looking to produce electricity alongside their dominant energy-generating peers, and it required utilities to provide open access to their "energy rate schedules" (or tariffs).

Order 889 came soon after, setting standards regarding information that utilities must make available to the marketplace, and establishing an online bulletin-board system for sharing the information.

Chester Smith is the former director of the Mississippi Department of Economic and Community Development's Energy Division, and the former chairman of the National Association of State Energy Officials. In 1996 he and Wilson Montjoy, an attorney with Brunini, Grantham, Grower & Hewes in Jackson, conceived an idea for new economic development based upon the tremendous amount of natural gas flowing through the state.

Mississippi is a state with a seaport, and that port is the first step in a long trip natural gas makes from foreign shores to destinations in the northeastern sector of the nation. Multiple gas pipelines course through the state, most connecting with power company behemoths like TVA, Southern Company and Entergy. Natural gas also had a relatively low price at the time. Why, reasoned Montjoy and Smith, should the state not be the manufacturing Mecca of electricity?

They hoped to link this readily available resource to the embryonic free-market meme coursing through the country. They carried their message of an open market in the once-monopolized power industry to other industry professionals and politicians like Jackson Sen. John Horhn, then-chairman of the state Senate Economic Development committee.

The two launched a concept called "Mississippi, the South's New Powerhouse," and sold it to investors with relative ease. In truth, the economic atmosphere provided its own impetus: Nobody was pushing down purchases at the time. Independent generators were already viewing the Southeast as an opportunity to move in and usurp aging clunkers like the Rex Brown plant with newer, more efficient models.

The owners of the sputtering antiques at the time were off snubbing U.S. regulations by investing heavily in largely unregulated countries like Australia, China, England and South Americawhere a rate of return could roam proud and free, unfettered with the inconvenience of being capped.

But the potential windfalls in non-regulated utility economies overseas also posed considerable risk. The American investors, including companies like Entergy and Southern Company, the parent company of Mississippi Power, lost money overseas and came home to re-invest in safer markets.

When they looked around at their old Mississippi stomping grounds, they found it blossoming with newer, more efficient power plants built by a myriad of upstarts.

The new plants, like the KGen facility, had popped up like mushrooms after a rainstorm in anticipation of the U.S. government following through with the 1992 Energy Policy Act and other federal laws intended to create an open market for the power industry. Things were, very briefly, looking problematic for the returning crew.

But then Enron made the news.

The Enron Excuse

In 2000, Enron was the seventh largest corporation in the U.S. The company was aggressive as hell, and deeply embedded in politics in the U.S., Britain and India. Company CEO Kenneth Lay was a close personal friend of President George W. Bush and his biggest campaign contributor. Bush got $1.14 million in 2000 from Enron employees, according to consumer watchdog group Public Citizen.

It was an age when regulators openly cut deals with the regulated: Vice President Dick Cheney even worked with Enron executives to craft a new national energy policy. A May 2001 New York Times article pointed out that Enron Senior Vice President Richard S. Shapiro said his firm's top executives spent "half an hour with Mr. Cheney," during the construction of the nation's energy policy. The results capitalized on the 1992 Energy Policy Act, and pitted of FERC orders 888 and 889 against traditional utility monopoly systems.

Critics accused Enron of exploiting the freshly deregulated utility markets, and deliberately obscuring profits (and losses) from both regulators and its own stockholderslong before the news and inquiries proved the suspicions true. The company's business model existed on the premise that it could make more money speculating on electricity contracts than by actually producing electricity at a power plant.

Public Citizen claims the central aspect of Enron's strategy of turning electricity into a speculative commodity "was removing government oversight of its trading practices and exploiting market deficiencies to allow it to manipulate prices and supply." California, like Texas, had bought into the concept of a free-market formula for its utility industry.

"What we saw was that some state public utility regulating agencies did such a bad job of regulating companies that they decided to break up the monopolies and brought in competition, thinking a free-market would do the regulating better," said Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen's energy program. "But deregulation had its problems. Regulation was something California couldn't do when Enron was wreaking havoc because when they deregulate the market they voluntarily cede state control over the market."

Enron's political friends, Bush and Cheney, battled against federal price controls in the California electricity market, allowing Enron to gouge customers for years, but when federal regulators finally did impose strict, round-the-clock price controls over the entire western electricity market in summer 2001, power auction companies like Enron could no longer charge excessive prices.

But Enron owed its existence to price-gouging. Once that tool was gone, its suffering assets could no longer cover its losses in the power auction market. The revenue loss also made it more difficult for the company to hide its sleight-of-hand practices. CEO Jeff Skilling resigned two months after regulators imposed price controls that June.

Shareholders caught wind of Enron's financial trouble by November. The drop in the company's stock price lost $11 billion for its stock holders. It filed for bankruptcy by December of that year, creating the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history until WorldCom topped it the following year.

Mississippi had only limited motivation to switch to a free-market energy economy in the first place. Unlike California, Mississippians' monopolistic system delivered relatively affordable utility bills. Attorneys representing the interests of new plants like the KGen facility report that investors halted construction on many proposed facilities, and even dismantled other nearly complete power generators.

"One facility in Kosciusko was completed to about a 90 percent level of completion, but a corporate determination was made that opportunities were not there, so the turbines were dismantled and the facility never completed," Montjoy said. "A number of large companies invested billions of dollars in pursuit of an opportunity that turned out not to be viable, and so their shareholders lost billions of dollars."

But Enron became the real poster boy for why dominant power companies should remain dominant. After its collapse, embedded power companies easily convinced policy-makers in the Southeast to drop the words "wholesale competition" from any sentence containing the words "utility industry," and there were no Enrons around to argue the point.

Hood to the Rescue?

Mississippi is not strictly monopolistic. It harbors several giants, including TVA, Entergy and Mississippi Power. Multi-company interaction is actually one of the key components in an agreement the state has with power companies: that state-supported power suppliers reach out to smaller, independent electricity suppliers for cheap electricity if the effort will result in lowered electric bills. Last year, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood alleged in a Hinds County Circuit Court lawsuit that Entergy and its various subsidiaries have been shirking that portion of their state mandate.

Entergy's dealings with the KGen plant could prove to be one of the more obvious examples of abuse, which Hood calls "dishonest practices worthy of Enron." Hood had previously filed suit against the energy provider in Hinds County Chancery Court last August to force it to surrender company information about the Louisiana utilities commission investigation finding Entergy liable to ratepayers for $72 million.

Delaney v. Entergy came down to LPSC reports revealing that Entergy Louisiana had opted out of a contract with NERCO Oil & Gas in favor of a new gas-supply contract between Entergy and Evangeline in 1991. Entergy paid fines resulting from the breach-of-contract suit through customers' fuel-adjustment charges, even though state law in both Louisiana and Mississippi say the only thing the company can pass along through fuel-adjustment charges are fuel costs.

Louisiana commissioners fined Entergy for the behavior, but Entergy assured Mississippi commissioners last year that customers here had not suffered fuel adjustment hikes as a result of the Evangeline contracteven though the state had some access to power generated through the contract.

Hood later updated his first suit with a more serious one alleging the company engaged in deceptive trade practices, antitrust behavior, accounting manipulation and unlawful enrichment, among other charges. Entergy inadvertently set both suits in motion after the company approached the Mississippi Public Service Commission with a request to raise ratepayers' energy bills 28 percent last summer. Commission members held a series of meetings grilling Entergy officials after the request, with Hood taking an interest in the debate.

Hood told reporters that the commission, with fewer than 11 staff members, didn't have the manpower to fully take on a company as big as Entergy and subpoenaed the supplier for 30 year's worth of information regarding its fuel-procurement practices. Entergy responded with a suit in U.S. District Court to block the subpoenas, prompting Hood to intensify the court battle with secondary litigation.

"We already have the documents we need to know that undercover things happened, and we know the evidence is there, so we feel very comfortable filing this suit," Hood said at a Dec. 2, 2008 press conference announcing the suit.

The new allegations, now awaiting a decision in U.S. District Court, claims the power company sold Mississippians a more expensive package of energy generated by Entergy affiliates instead of by cheaper, independent sources like KGen. Buying from your subsidiaries offers the plus of raising your company stockand Entergy's stock weathered the recent economic catastrophe better than most.

Hood says the company also "fraudulently claimed" to the Mississippi Public Service Committee that it was following the state mandate of selling cheaper power from independent sources to Mississippi customers while doing nothing of the sort. Entergy does make use of comparatively inexpensive third-party powerbut instead of passing savings on to Mississippi consumers, Hood says it has been selling that cheap electricity to other energy companies that are not Entergy affiliates at an unregulated profit.

The company denies the allegations. Robert Cooper, manager of Entergy Services Inc., testified before the Mississippi Public Service Commission last summer, stating that the projected fuel costs for power purchased during the third quarter of 2008, for example, were "reasonable estimates of the costs needed for (the company) to continue to provide reasonably adequate electricity service to its customers at the lowest reasonable rate."

Entergy Mississippi spokeswoman Mara Hartmann echoed Cooper's argument this week, saying the company is driven to pass along to customers the cheapest, most affordable power is can get. "Because we do have a monopoly here in Mississippi, we have an obligation to provide the safest and most reliable power at the most affordable rate possible. We do buy from independent power providers, but we have a very competitive bidding process, and it is incumbent upon us to purchase power at the most affordable rate possible," Hartmann said.

Hood's suit extends beyond allegations of inflated price, also questioning how Entergy spent its money. Entergy used Mississippi ratepayers' cash to finance the operation of nuclear plants in the Northeast, behavior that Hood questions because the Mississippi Public Service Commission exerts no regulatory authority over operations in the Northeast.

Nuclear power is apparently hard to maintain. SEC filings show that Entergy in 2007 spun off its nuclear division into a company called Enexus Energy Corporation. A May 12, 2008, SEC filing revealed that the nuclear-power division got $1.2 billion in loans and a $1.9 billion obligation guarantee from "associated companies," which happened to include Entergy Mississippi.

Hood stated: "Entergy Mississippi placed its assets, revenue stream and creditworthiness at great risk by making these large loans and guaranties in favor of its parent's unregulated nuclear generating business."

The northeastern portion of the parent company also benefited from the 2005 devastation that Hurricane Katrina brought to Mississippi. Information in Entergy's November 2007 quarterly report, filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, does indeed point out that Entergy Corporation received a $344 million income-tax refund in 2006, including $71 million attributable to Entergy New Orleans, through the Gulf Opportunity Zone Act of 2005. "In accordance with Entergy's intercompany tax allocation agreement, $273 million of the refund was distributed to the Utility business in April 2006, with most of the remainder distributed to Non-Utility Nuclear," the report states.

Hood questioned why Entergy should divert $71 million of the $344 million income tax refund (about 21 percent of the refund), away from affiliates like Entergy Mississippi, which actually suffered under Katrina. Katrina was a late summer breeze by the time it reached the Northeast, after all.

Hartmann said the federal government had intended for the northeastern sectors of the parent company to get the money as reimbursement for their investment in repairs to the Katrina-struck South.

"These are all subsidiaries, and every one of them contributed to that 2005 net operating loss, so it was entitled to a share of that refund on a pro rata basis," Hartmann said. "If they had a net operating loss that year, they were entitled to a share of the refund, and they did. There was no refund diversion to anyone. They suffered the loss, so they got part of the money back."

Lost in Louisiana

Hood leans heavily upon recent events in Louisiana to support his allegations of unfair trading. The New Orleans case, Gordon v. The Council of the City of New Orleans, is an entry in Hood's lawsuit against Entergy Mississippi because the New Orleans City Council concluded that Entergy had engaged in the practice of inflating prices to cover costs not allowed in New Orleans' fuel adjustment charges. The council accused Entergy New Orleans of charging customers to finance the cost of System Fuels Inc., another Entergy company formed to buy fuel for Entergy affiliates. The council ordered Entergy to repay $11.3 million, but some New Orleans residents and business owners felt the fines didn't reflect the offense.

The council's own advisers had actually recommended fining Entergy $34.3 million, not $11.3 million, so the residents appealed the decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals last year. That court, basing its decision upon the $72 million decision of the Delaney case, ruled that the council's $11.3 million refund was disproportionate to the Delaney case refund.

The Louisiana Supreme Court came along and reduced the circuit court's $34.3 million back to $11.3 million. Though they did not overturn the case, John Mullins, vice president of customer operations for Entergy Mississippi Inc., heralded the decision a triumph.

"The Court concluded that Entergy acted in good faith and with no intent to harm our customers, just as the city council had previously concluded," Mullins said in a company press statement.

Mullins then used the reduction as an argument against Hood's suit: "Additionally, this decision demonstrates that although the AG tries to act as prosecutor and judge at the same time, mere claims of wrongdoing do not prove wrongdoing in our legal system."

The company initially claimed that events in Louisiana had no bearing upon Entergy's electricity prices in Mississippi. Entergy CEO and President Haley Fisackerly told 16 WAPT News last October that the Louisiana case had "no relevance to the Mississippi ratepayers or to our cost of business here in Mississippi."

But this past January, Entergy officials told members of the Public Utilities Staff and counsel for the Mississippi Public Service Commission that the company was mistaken when it stated that the activities in Louisiana did not affect Mississippi ratepayers.

The very next dayperhaps in a show of thoroughnessthe PSC issued an order mandating Entergy commit its admission to writing. In the resulting Jan. 8, 2009, letter to the commission, Entergy stated that "in the course of the companies' continuing review of the facts in connection with this matter Entergy Mississippi and Entergy Services now have reason to believe that beginning in January 2005 energy produced by the Evangeline (Louisiana) gas contract has been sold into the Entergy exchange and may have an effect on the costs paid by Entergy Mississippi customers."

Later, the company also revealed to the PSC that the awkward Evangeline contract in Louisianawhich Entergy had initially claimed had not affected Mississippi ratepayers outside the window of the years 2005-2008may have extended further back than it had initially told Mississippi commissioners.

Hartmann said the two corrections resulted from nothing more than the power company's continued diligent efforts to audit its numbers.

"We've got thousands of documents that must be reviewed. There are literally hundreds of fuel purchasing transactions per day, thousands per week. That's why it's taking us so long to do such a thorough review," Hartmann told the Jackson Free Press in January. "And as we go through this lengthy and complex analysis we'll be keeping our customers informed of our findings."

Entergy has been decidedly less repentant to Hood, withholding office company information that he considers vital to his lawsuit against Entergy. The company has also attempted to get Hood thrown off the case as Mississippi Public Service Commission's attorney, asking for an April 17 order barring Hood's office, or any contractual attorneys associated with him, from access to Entergy documents. Entergy claims Hood has been acting in three conflicting roles on Entergy-related matters: as both counsel and advocate for the commission and "as an advocate before civil courts."

The company also wants a protective order to keep company trade secrets confidential and safe from Hood's employees and attorneys doing contracted service with Hood's office. Robert Greenfell, Entergy Mississippi vice president for regulatory affairs, said at a June Federal Energy Regulatory Commission forum that Hood is looking for documents going back decades that would fill about 15 trucks.

"That's why we sued him in federal court," Greenfell told Electric Power Daily, referring to the request for protective order. "We have offered to provide these documents to the Mississippi Public Service Commission and FERC, and (Hood) refused."

Hood said the documents would be inadmissible in court if presented to another entity like the PSC. The PSC is playing along with Hood's side and has refused to take the documents, instead ordering Entergy to hand them over directly to Hoodan order Entergy is still currently refusing.

The company has also filed for a change of venue, looking to get Hood's suit moved to federal court, arguing that Hood's suit qualifies as a massive tort action that falls under the Class Action Fairness Act.

Reporters quoted Chicago attorney David Carpenter, who represented the power company during the May 28 and May 7 hearings before U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate, that "Hood has named four different defendants: Entergy Mississippi, Entergy Corporation, Entergy Services and Entergy Power."

Hood says the state has policing powers over monopoly utility companies, so the case should play out in state court. Wingate said in early June that he would rule within three weeks to 30 days on Entergy's motion for change of venue request. Wingate had yet to rule as of Aug. 13, leaving the ruling about five weeks overdue.

FERC'ed Again

A monopoly system apparently puts power in places where it's hard to extract. Public service commissioners from four different states blasted Entergy in June at a joint meeting of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission technical conference in Charleston, S.C. Commissioners said Entergy refused to build more transmission lines and restricted access to low-cost electricity, implying that it was attempting to squeeze out competitors from places like Mississippi.

Entergy, they say, refused to follow the recommendations of the Southwest Power Pool (a nonprofit corporation acting as a Regional Transmission Operator) to build more transmission lines. Electric Power Daily quoted FERC Chairman Jon Wellinhoff warning Entergy that they were putting themselves at sizable risk for a lawsuit, creating "a lawyer's dream" if Entergy's behavior "cause specific damage to consumers."

State commissioners from Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas who attended the meeting also criticized the power company for the practice.

FERC officials even requested Hood attend, and he seemed more than happy to set the mood of the meeting, particularly regarding what he viewed as Entergy's transparency problems.

"Our goal is to find the truth," Hood told the forum. "What we find is that Entergy has, at every turn, tried to thwart our statutory authority to enforce PSC law."

Greenfell then rose and asked for a chance to rebut Hood's claims, declaring that he had not expected Hood to be putting on a show for the board. Wellinghoff shut Greenfell down, saying, "No, you can sit down."

Greenfell didn't get the message, however, and mistakenly began to take a seat before a microphone. The chairman stopped him and re-directed him to go back and sit in the audience.

Tension is nothing new between FERC and Entergy. FERC had already found Entergy guilty of bid rigging in 2006, by sharing pertinent information on energy bids with its subsidiaries, giving them considerable advantage in the process.

The organization warned in a September 2006 decision that "if such violations occur in the future, the commission will consider civil penalties as a potential remedy," adding that, going forward, FERC expected Entergy to strictly adhere to guidelines, and threatened to invalidate wholesale contracts that are determined by FERC to be the product of bid rigging.

A New Standard

Mississippi Public Service Commissioners Brandon Presley and Lynn Posey attended FERC's unprecedented joint meeting with Entergy and state commissioners in June. The two profess to have a strong interest in acting as true watchdogs over the utility company.

"We've taken the word of the people we're supposed to be regulating for too long," Presley said in January. "It's time for changes." Even Public Citizen's Slocum questioned the effectiveness of the Mississippi Public Service Commission if the responsibility of policing Mississippi's power companies kept falling to the state AG.

"This case between Hood and Entergy confuses me because if this amount of trickery has been going on all this time, where was the state's public utilities commission? They have total regulation over Entergy's operations and the PSC's charge is to ensure that they are overseeing the process by which Entergy is supplying power for the least cost mechanism," Slocum said.

"If they're failing to do that, you all need to get rid of your PSC. I mean, the AG ought to be filing ethics complaints against the PSC if he has evidence that a company fully regulated by a state commission is gouging the public."

A new Mississippi Public Service Commission emerged after the last elections, and started making real ripples in the old way of doing things this January.

The commission had already launched an investigation in 2008 over Entergy's requested 28 percent rate hike, but the commission exhibited real frustration in January at conflicting reports from the PSC's sister agency over an audit of Entergy's fuel adjustment. In a move that stunned the state, commissioners refused to sign off on an audit report prepared for the state Legislature by the Public Utilities Staffa group not elected like commissioners but under the auspices of the governor, who appoints its leader. The PSC claimed that the report did not answer all the questions that Mississippi ratepayers needed answered.

Commissioners Posey, Presley and Leonard Bentz claimed that the audit, submitted by the Public Utilities Staff, which handles accounting for the PSC, did not completely depict whether or not Entergy bought the cheapest power availablean argument that just happened to fall in line with the 2008 lawsuit Hood launched against Entergy.

"The key to all this is whether or not that $471 million fuel adjustment charge in the last year is the best price we got, but we can't conclude that because the procedure that's gone on here for years has not looked into that," Presley said in January.

Hartmann said this week that one of the functions of the PSC is to lay to rest questions over whether or not companies like Entergy were truly buying the cheapest power possible and passing those savings along to customers, adding that the company has "always been in compliance with the regulations that the PSC has set forward."

Public Utilities Staff Executive Director Bobby Waites told the Jackson Free Press in January that his staff thoroughly checked Entergy's numbers to make sure the fuel adjustment charges were accurate, as demanded by state law. But Waites told the commission that same week that while the audit his staff submitted fulfilled the state's legal requirements, it did not determine if Entergy Mississippi's procurement was at the "rock-bottom lowest price."

"There's no way we can look at each one of thousands of transactions to determine if each purchase made should have been made instead of the one that wasn't," Waites said.

Presley expressed frustration at two seemingly contradictory assessments from the same person, as well as deep regret over the separation between the PSC and PUS.

"The commission is severely handicapped by the setup in which all the accountants are invested in the public utilities department, and we don't have any staff. We have eight staff members. They have about 30. There's no other state in America where the staff has all the resources and no accountability, and the commissioners have all the accountability and none of the resources," he said.

The Legislature put the PSC's accountants into the fledgling Public Utilities Staff department in 1990 as a knee-jerk reaction to Public Service Commissioners David Snyder and Lynn Havens being convicted of extortion, bribery and conspiracy.

Snyder had arranged PSC approval of a power company's rate increases in return for that company's favorable treatment of businesses owned by Snyder and his friends. He also failed to report his bribe money to the IRS as income.

Power-company advocates seem to prefer a split. This year, the PSC pushed the Mississippi House of Representatives' Public Utilities Committee to pass a bill moving the Mississippi Public Utilities Staff back under the supervision of the Public Service Commission. Power companies had more than 20 lobbyists working the Legislature, and Presley said he suspected their bill died under the whispered demands of those same lobbyists this year.

The House and Senate managed to produce an appropriation bill this year financing new PSC staff members to check power companies' accuracy on fuel adjustment practices, but Gov. Barbour, a former lobbyist whose firm represented Southern Company, refused to fund the PSC at the last minute.

Hood said he believed power companies shut down the appropriations process expressly to remove the new staff members.

"If you watched the debate on the Senate floor, it should have been sickening to you. It's just like what happened with Wall Street in Congress," Hood said in July. " [Y]ou saw companies like Entergy using their muscle. All the Republicans voted to take the staff away from the Mississippi Public Service Commission. They had an agreement, but then Governor Barbour told the lieutenant governor to pull the plug on the agreement."

Sen. Alan Nunnelee, R-Tupelo, confirmed that Senate negotiations on PSC funding were shut down because of the 11 proposed new employees, who he said represented "a duplication of government."

"These new employees are an effort to expand the PSC and duplicate what the Public Utilities Staff does," Nunnelee said, arguing that the state should not have to fund new positions during hard financial times.

Posey and Hood pointed out that the staff positions were fully funded by utility companies through user fees, however, not taxpayers. But the following week, Senate opponents adjusted their argument, claiming the extra costs would only come out of rate-payers' bills. Posey countered that ratepayers' bills would have gone up no more than seven cents per month with the 11 new employees, explaining that the money customers would save because of the additional scrutiny would be considerably more than that.

Senators eventually allowed in three new employees whose wages were already set aside in the PSC's budget during the most recent special session. The effort truly amounts to a reshuffling of positions, however, so the effectiveness of the move has yet to be determined.

A Show of Reform

The new and improved PSC actually started making an impressive show of reform even before the new employees set up shop.

Mississippi Power Company filed a Jan. 16 certificate of public convenience with the PSC, asking for permission to begin setting aside 48,000 square acres of Kemper County land for lignite coal-mining, and the construction of a 582-megawatt lignite coal-burning plant using technology that, at the moment, doesn't really exist.

"This plant will diversify our fuel sources and will produce energy at lower and more stable costs than any other fossil fuel option," said Anthony Topazi, Mississippi Power president and chief executive officer in a statement.

The Mississippi Sierra Club has joined the AARP and Kemper County residents in opposing the roughly $2 billion proposal. Mississippi Power initially said the proposed integrated gasification combined cycle, or IGCC, plant will sequester 50 percent of its carbon emissions, making the plant eligible for federal funding, but Sierra Club Director Louie Miller said the technology currently only exists in "some advertising guy's imagination."

Miller and the AARP still oppose the plant today, even after Mississippi Power told the Associated Press this week that the facility will be upgraded to capture 65 percent of its carbon, as opposed to the 50 percent target in earlier design plans. Mississippi Power upgraded the design in order to claim more federal subsidies. The resulting federal subsidies could reduce the cost of the plant from a $2.8 billion figure reported by the Sierra Club to $2.2 billion. But Miller said ratepayers don't know what kind of rate increase to expect from the venture.

"We don't know because they're keeping them confidential. If Mississippi Power is about transparency, then they need to quit hiding behind these confidentiality agreements and put these numbers on the table so customers can see what kind of increase they'll see on their bills," Miller said, adding that construction of Entergy's $3 billion Grand Gulf nuclear power plant increased Entergy's rates about 60 percent.

Although the investment cost of Grand Gulf and a proposed sister reactor unit had been estimated by Entergy to be $1.2 billion, the investment cost of the first Grand Gulf alone was approximately $3 billion due to regulatory delay, additional construction requirements, inflation and increased financing costs. Entergy had a customer base of 300,000 to absorb that increase, however. Mississippi Power, comparatively, has only 186,000 customers who will have to absorb the Kemper plant's cost of $2.2 billionproviding the company manages to nab about $600,000 worth of federal subsidies.

Mississippi Power spokesman Todd Terrell did not return calls.

Craig Roach is president of Boston Pacific Company Inc., and a recent adviser to the PSC during its deliberation over the Kemper County plant.Roach said that if the plant's costs were put into rates, then "MPS's rates would increase substantially as compared to rates today." He even questioned whether the increases would be devastating enough to push customers to cut off their lights and lower the electricity demand that MP claims as their very reason for building the facility.

"It is important that (Mississippi Power) ask whether the rate increase caused by the IGCC plant itself could actually reduce peak demand and energy use and, thereby, obviate the need for some or all of the plant," Roach said, implying that the rate increase would have to be substantial indeed to drive Mississippians to forsake 582 megawatts of electricity.

Miller says the increase isn't even necessary, because the state already has "almost 8,000 MW of power, a lot of it just sitting around unused."

Beating the Political Heat

When Miller speaks on the 8,000 megawatts of power "just sitting around," he's referring to the more than 7,666 megawatts available to the state from smaller, independent power set-ups like the largely abandoned KGen facility in Jackson. That potential electricity already available to the state is three times what the largely rural state needs, even on peak demand days.

Nevertheless, energy industry lobbyists piled onto Mississippi legislators during the 2008 and 2009 legislative session like third-graders on a pizza, pushing for state laws and incentives that would help fund the new Kemper County facility, and planned expansions at the Entergy-operated Grand Gulf nuclear facility.

In 2008, they got what they wanted: Legislators passed a new law designed to finance costly projects. Entergy officials told The Clarion-Ledger in 2008 that they hoped to see a 1 percent rate increase in 2009 to fund the $5 billion construction at Grand Gulf, a project later abandoned in lieu of a reactor expansion. (The PSC is considering Entergy's new application for expansion now.)

Legislators also passed a bill during the 2009 legislative session giving a massive $1.4 billion tax cut for the Kemper plant, despite lobbyists initially misleading legislators about the actual amount of the tax cut.

"There's always a lot of lying going on here," House Ways and Means Chairman Percy Watson told the Jackson Free Press in March after admitting the bill was still probably going to make it out of his committee.

Mississippi Power advocates were playing down the numbers that month, telling legislators that the exemption only amounted to $4 million over 40 years, when language in HB 1639 stipulated a tax cut of at least $1.32 billion over the four-decade life of the plant.

Mississippi Power spokeswoman Cindy Duvall assured the Jackson Free Press earlier that month that the bill would only allow tax exemptions for the portion of the plant that turns lignite coal into a gas.

Even Kemper County Sen. Sampson Jackson, D-DeKalb, who authored the Senate version of the tax deduction, SB 3201, said representatives of the Mississippi Development Authoritycontrolled by Gov. Barbourhad misled him into believing that the exemption only applied to a portion of the plant.

Mississippi Power lobbyists came clean later in the session, but legislators obviously accepted whatever apology they gave. Both the House and Senate passed the bill before the end of March.

Despite the pro-utility wind coming out of the Legislature, commissioners know their return to office in the next election cycle banks on their ability to keep rate-payers' costs low. And some are beginning to foresee problems if the two new projects come to fruition.

Commissioners, after all, brought in Roach to personally investigate the Kemper County project, and Roach was not a gentle critic. He hurled all manner of questions at the company, such as whether or not the company was putting adequate investment into trying to reduce the need for power on the buyers' end, like neighboring power company Georgia Poweror even Mississippi Power's parent company Southern Company.

Roach also pointed out in his report that Mississippi Power appeared to give no consideration to the fact that industrial and wholesale customers account for 74 percent of the state's rising future energy needs, not residential ratepayers. Roach explained that the risk needed to shift from residential and commercial ratepayers to the industrial and wholesale customers "who appear to be driving MPC's justification for the plant."

Commissioners are mum on any premature opinions of the plant, but they have indicated through decisions that they will be slow to lob its new cost onto customers. They voted in June against fast-tracking their decision on the plant, and on beginning the process for approving the plant's pre-construction costs incurred between March 31, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2009.

The commission voted unanimously to refuse that request, arguing that the PSC must first "evaluate the company's decisions leading to these costs," which is the purpose of the PSC's two-year deliberations.

The Public Service Commission will begin hearings on the feasibility of the new coal plant Oct. 5, and Miller says he doesn't know how to read their take on it so far.

"Who knows if the politicians trying to get to them have gotten to them. I know the power companies are putting the heat on them through state government. That was obvious in how the Legislature treated them this summer, cutting their funding for a few days. These guys are really feeling it from the industry," Miller said.