Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba sits in on the Commission on School Accreditation meeting on Sept. 13 where it voted JPS is in an “extreme emergency.” NAACP Interim President Derrick Johnson and Sen. Sollie Norwood, D-Jackson, sit to his right. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

The afternoon of Thursday, Sept. 14, seemed to creep by slowly as Mississippi Board of Education members deliberated the future of Jackson Public Schools behind closed doors. The boardroom buzzed with conversation, sometimes lively, sometimes in hushed whispers. JPS and Mississippi Department of Education officials, community members and a few parents waited on the fourth floor of the Central High School Building to hear the board's decision to declare an "extreme emergency" in the second-largest school district in the state. One MDE employee brought back a cup of candy from her office, offering it to not just her friends, but also anyone she passed.

About two and a half hours later, the State Board returned, lugging large binders that contained the almost 700-page MDE investigative audit as well as the JPS response to the report. The long deliberations did not help JPS, however, and Board President Rosemary Aultman delivered the verdict, reading from a paper at the front of the room. She said the board decided to declare an "extreme emergency," and went on to name an interim superintendent, Margie Pulley, who would assume control of the state's largest urban district once Gov. Phil Bryant signs the resolution.

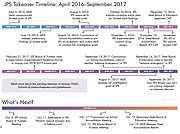

The State Takeover of JPS

JFP's stories about the state takeover of the Jackson Public Schools district

JPS Board of Trustees member Jed Oppenheim stepped up from his chair and walked out of the room before Aultman had finished reading, visibly upset.

"What we are seeing is a re-colonization of our city by the state—this is not about children, this is about money and power," Oppenheim told reporters outside the old Central High School, repeating what he'd said in the hallway moments before. "The State of Mississippi has never cared about the black children in Jackson, and they're not about to start right now."

A frenzied press conference of state and local elected officials and parents echoed a singular sentiment: While JPS has problems, we don't need the state to fix them.

"We've got some challenges, but I guarantee you that you can go to any school in any school district and you can find these very same challenges," Sen. Sollie Norwood, D-Jackson, who sat dutifully through both the commission and board meetings Sept. 13 and 14 said. "... This process to name an interim superintendent with the interim superintendent in the room? That's absolutely disrespectful."

The mood was glum outside, and JPS parent and local attorney Dorsey Carson announced his intentions to file a federal lawsuit over the process, noting that parents had no say in the investigation, audit or "extreme emergency" declaration process.

"Every child in Mississippi and every child in the nation where a state provides public education, they have due-process rights in that education," Carson told the Jackson Free Press in an interview later that week. "It's considered a property interest ... how do you take away their property right to a public education in a process that completely shuts out the parents?"

Carson received strong support for his lawsuit, and by the time he filed it Sept. 18, 30 parents had joined him asking the federal court for relief.

The Governor's Call

Jacksonians will have to wait on Gov. Bryant's decision, set to be made next month. The governor gets the final call on whether to pull local control from the state's second largest district, dissolving the local school board and installing Pulley as interim superintendent. The governor is in no rush, however, signaling a shift from previous takeovers in the state, where he would sign a "emergency" declaration shortly after the state board's decision.

"This is a very important decision that will be made," Bryant told reporters on Sept. 20 at the Capitol. "I certainly respect the (state) board's decision to send me that request for emergency, but we are going to make sure that we know exactly what the condition of the city of Jackson public-school system is now—that that wasn't just a snapshot that occurred."

Bryant's decision to hold off judgment means his staff will review the almost 700-page audit of JPS that the Mississippi Department of Education released at the end of August. He can also read the district's response, which JPS furnished to the Commission on School Accreditation and State Board members earlier this month as administrators argued that no state of "extreme emergency" exists in the district.

On Sept. 14, the state's Commission on School Accreditation voted to declare an "extreme emergency" in JPS, and the Mississippi Board of Education affirmed their decision the following day. MDE auditors found JPS in violation of 24 of the state's 32 accreditation process standards. The district violated several standard areas from how the district manages curriculum to school building safety and insecure state testing environments, the audit show. MDE auditors found JPS staff and teachers using electronics during state testing or in some classrooms, children unattended at all.

Gov. Bryant told JT Williamson on his SuperTalk radio show that he will wait until MDE releases final accountability ratings of schools districts in October to make his decision.

"I am going to do what I believe is best for the students, not the administration not the faculty, what's best for the students' learning and safety environment in the city of Jackson," Bryant told Williamson.

"The final decision on this process, if you will, is on the 19th of October (when) the state department will give its final approval to determine if for the second year in a row if the city of Jackson is rated as an 'F.' That's one of the indicators or triggers, if you will, that would add to a declaration of emergency. ... I think it would be prudent on our part to wait until at least that day to see what the decision of the state board of education will be in rating the school district—that will go a long way in helping make that decision."

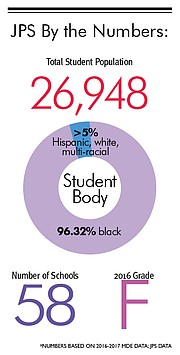

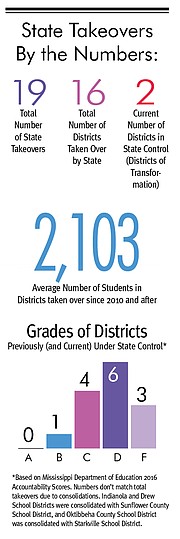

JPS received an "F" grade in the 2016 accountability rankings, and preliminary data from MDE, used against the district during the Commission on School Accreditation meeting this month, show that the district will receive an "F" in October as well. All of the state's "F" rated school districts are majority-black districts, and all of the districts taken over by the state since 2010 are also majority-black districts, with one exception. Scott County School District, which has improved to a "B" grade since the state took it over, is 48 percent white; 38 percent black student population. It also has the highest grade of any district ever taken over by MDE.

Race and takeovers can go hand-in-hand. A study of Louisiana parishes and support for a ballot initiative authorizing Louisiana's takeover law in 2003 found that resistance to the measure was strongest in parishes with the largest African American electorates.

"These data do not indicate why individuals oppose state takeovers, but resistance appears to stem from the fact that Louisiana assumes control over predominantly African American school districts in general, and New Orleans in particular," Peter Burns wrote in his 2010 study.

JPS is a majority-black district, with African American students making up over 96 percent of the student body. The governor told reporters there have been issues in JPS for a decade, and leaders should have addressed those issues long ago.

"Now that the alarm has been sounded, everyone wants to rush in: where were they when we needed them a decade ago?" the governor said last week.

The governor has met with Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba, Jackson lawmakers and Interim JPS Superintendent Freddrick Murray. If Bryant chooses to sign the resolution declaring an "extreme emergency" in JPS, the district will lose local control and access to their schools immediately.

District of Transformation

Few people expected the governor to take his time making the decision. The Sept. 19 JPS School Board meeting was eerily empty, save a large number of district officials. The board passed a resolution to allow local PTAs and school communities to change their school names associated with Confederate leaders, in fear that they would not be able to meet again.

Acting JPS Board of Trustees President Camille Simms gave shout-outs to several district leaders, applauding their work, toward the end of the meeting, in what seemed to be a swan song.

"I feel like this really the end as we move forward, but really not the end, when I say the end, we are really not in the end position, we are moving forward," she said.

"I know some people have thought (about) what the governor is going to do, what is going to happen, we don't have a clue. ... We are moving forward, educating our children."

The next JPS board meeting is scheduled for Oct. 3, and business continues on in the district as usual until Gov. Bryant declares an emergency. Pulley, for her part, is still acting as the interim superintendent in the Tunica County School District.

When the governor declares a state of emergency in a school district, he immediately dissolves the local school board and puts the Mississippi Board of Education over the district. Before state law changed to manicure the language used for state takeovers, deeming them "districts of transformation," they were called conservatorships.

Now, instead of naming a conservator, the state board named an interim superintendent. Paula Vanderford, the chief accountability officer at MDE, told reporters Sept. 14 that Pulley would take over district operations if Bryant declares an emergency.

"The placement of the interim superintendent would be effective immediately, so the timeline from that point forward regarding any personnel decisions in the district would be left to the interim superintendent," Vanderford said.

While Murray would obviously lose his superintendent title, the rest of JPS staff and personnel would also be subject to Pulley's direction. Pulley and the State Board of Education could reduce the local supplements paid to school district employees, state law says, if the district's impairment is related to a lack of financial resources.

The City of Jackson would lose control of the school district because the emergency declaration dissolves the local school board, which only has four members at the moment. The mayor appoints school board members, and the city council confirms them for five-year terms.

When the State Takes Over

Tunica County School District is one of two districts of transformation in Mississippi currently. Pulley is serving as the interim superintendent at the district now. Pulley, a former superintendent of the Greenwood Public School District, abruptly retired from her post back in 2012, only to get back to work as the conservator of Oktibbeha County School District in January 2013. Pulley moved from Oktibbeha—which has since consolidated with the Starkville Public School District—to Tunica in 2015.

Messages and interview requests left for Pulley at the superintendent's office in Tunica School District remained unanswered by press time.

Tunica schools, which have a little over 2,000 students, improved from a "D" to a "C" ranking under Pulley's leadership in just one year, but some parents feel shut out of the schools now that the state is in control. One parent with two children in Rosa Fort High School told the Jackson Free Press that access to school leaders and teachers completely changed when Pulley and the state, took over the district.

"Before she came in there, if a teacher had a problem with her child, you can call back to the school and connect you to that teacher's classroom," the parent, who wished to remain anonymous, said. "Now you can't even go to the school and check on your child, you have to stand outside and stand 40 feet away from the office building. ... It's like Parchman, you have to go to a check-in gate."

The parent said other folks in the community refer to the high school as "Fort Knox" now, due to the changes.

Pulley, whose main charge is to improve academic achievement in the district, is known for her no-nonsense approach. A 2005 Leflore Illustrated article profiling Pulley said she "exemplifies the iron fist inside a velvet glove." Pulley worked as a teacher, principal and eventually, superintendent of the Greenwood Public School District.

As principal of Threadgill (Elementary) School, the Leflore Illustrated article says, Pulley eliminated recess at one point to take control of a "sometimes rowdy campus." Corporal punishment was a part of Greenwood's handbook during Pulley's tenure and was in 2015, too, The Washington Post reported.

Both districts of transformation (Tunica and Leflore) in the state each have less than 3,000 students. Greenwood School District has less than 3,000 students also. JPS, on the contrary, has almost 27,000 students by last year's count (enrollment is down, however, and that number is closer to 25,000-26,000 this school year). The State Board trusts Pulley to turn schools around.

"Dr. Pulley has a record of transformation; she has done an amazing job in the other districts where she's worked," Aultman told reporters Sept. 14.

"She's a strong academic person; she has a background as an academic officer, so we have every confidence ... that she can come in and begin laying the groundwork to transform this district."

Do Takeovers Work?

Advocates of local control for JPS decry the state's track record on takeovers.

"Look, we know there are a number of problems JPS faces, but the record that the state department of education has with transforming school districts is dismal," Ward 2 Councilman Melvin Priester Jr. said outside the old Central High School on Sept. 14. "It will result a loss of services for children; it's not going to make children in JPS have better outcomes—it's going to make things much, much worse."

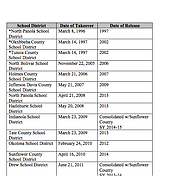

MDE has completed 19 takeovers total, of 16 school districts. The State Department had to re-takeover three districts: North Panola School District, Oktibbeha County School District and Tunica County School District.

Of the districts MDE has taken over, results vary. The majority of districts under state control at some point since 1996 have a "D" grade in the state's 2016 accountability rankings. One district, Scott County School District, has a "B" grade; four districts have "C" grades; and three districts returned to local control continue to be failing, "F" rated, districts.

This past spring, the Legislature changed how takeovers work: state law now requires districts to maintain a "C" grade for five consecutive years before returning to local control—unless the Mississippi Board of Education decides otherwise.

State takeovers as a policy practice are used in about half of states nationally, and on the whole have very mixed results. A Rutgers analysis of state takeover policies says very little research has been conducted on the effects of takeovers.

State takeovers can eliminate nepotism, improve administrative and financial practices and implement innovate programs, the Rutgers 50-State report says.

"However, student achievement oftentimes falls short of expectations after a state takeover," it says.

A 2002 policy brief from the nonpartisan Education Commission of the States emphasizes the Rutgers analysis.

"When state takeovers placing the state department of education in charge of school districts produce administrative and political turmoil, student achievement suffers. After a period of adjustment, however, these takeovers may also be able to produce positive achievement gains," the brief says.

What's Next?

October looms ahead for JPS, as the Commission on School Accreditation is set to meet on the 17th and could vote on whether or not to remove the district's accreditation status. If the Commission votes to remove JPS' accreditation, students are free to transfer to neighboring school districts that will take them.

Additionally, it starts a year-long countdown for improvement. If the district does not improve in that time, interscholastic activities, including all sports, dance, band and debate teams, are cut in half. Students continue to receive credits and will be able to graduate.

In federal court, the defendant's answers to the JPS parents' request for injunctive relief is due Oct. 11. State accountability results will be released Oct. 19, and Gov. Bryant, assuming he keeps his word, will decide then who he wants to control JPS.

To read more about the JPS takeover visit jacksonfreepress.com/jpstakeover. Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].