Rap changed the day Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five released "The Message" on Sugar Hill Records in the summer of 1982. This was the first time that the spoken-word technique of hip-hop music took any sort of political action. Its lyrics were an effective plea for help, set to rhythm.

"Broken glass everywhere, people pissing on the stairs, y'know, they just don't care" was the "I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired" to young black voices of New York City at the time.

Politics tore apart much of the city. Crack cocaine was on the bubble of becoming the popular street drug of choice, ripping communities apart, along with an influx of violence and poverty. Many families in the South Bronx, the area often credited with inventing hip-hop culture, were still recovering from the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, completed a decade earlier. The structure displaced thousands of residents, most of whom were black and Latino.

"The Message" gave birth to the tradition of rap activism. Highlights in its development include the rise of Public Enemy, from their video for "Fight the Power" to their video for "By the Time I Get to Arizona," a scathing commentary on the state's reluctance to implement Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday as a holiday.

Black Nationalist themes and personas filled the 1990s, as the Nation of Gods & Earths, an off-shoot of the Nation of Islam, implanted their teachings into the rhymes of Brand Nubian, Poor Righteous Teachers and Gang Starr.

Even when rappers aren't recording, they promote activism. In 2005, Kanye West shocked the world with his "George Bush doesn't care about black people" diversion on live television. Immortal Technique used money from benefit concerts to build an orphanage in Afghanistan. Mos Def even videotaped himself enduring heinous torture techniques, in protest of interrogation tactics at Guantanamo Bay.

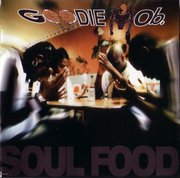

Below the Mason-Dixon line, some artists use their platform to promote community awareness. Goodie Mob's 1995 opus, "Soul Food," is a worthy example.

The Atlanta, Ga.-based quartet consisted of Big Gipp, T-Mo, Khujo and the fierce-tongued poet now known to pop-music enthusiasts as the "F*ck You"-crooning Cee-Lo Green.

Fans of Cee-Lo Green's stint as one half of Gnarls Barkley should feel at home upon pressing play on the 19-song collection. "Free," the album's introduction, sets the tone with a short, organ-assisted spiritual, sung solely by Green.

"But I won't accept that this is how it's gon' be, Devil, you got to let me and my people go," Cee-Lo sings before the refrain, "'Cause I wanna be free, completely free."

The song begins to fade along with the beginning of the second verse, creating the illusion that, much like this particular spiritual, the struggle itself never ends.

The single, "Cell Therapy," peeks out of the windows of a house in the archetypical southern ghetto in an identical fashion to Flash's "The Message." All four members point to issues within the streets they frequent—drug abuse, sexual promiscuity, violence and the distrust of the political reasoning behind Section 8 housing. The second verse ends on an inquisitive note: "But every now and then, I wonder if this gate was put up to keep crime out or keep our ass in."

Goodie Mob anchors the middle of the album with "Guess Who," an ode to mothers who support the family unit of the black community. Women with the strength to do so without the presence of a proper male figure in their households get a specific nod.

A prayer leads listeners into "Fighting," a hard-hitting cut interrupted by a soliloquy from Green, who begs for the listener to reverse the residual effects of slavery in the U.S. "You'll find a lot of the reason we behind is because the system is designed to keep our third eyes blind," he says.

The title track rounds out the last half of the album with an upbeat song that laments the feeling of gathering around to eat grandma's good cooking.

Interestingly, it is one of very few feel-good songs on the album. The characteristic warm comfort of the traditional African American cuisine the project is named for is largely absent. Instead, this album is one hearty helping of meat-and-potatoes music.

Cold. Hard. And to the point.