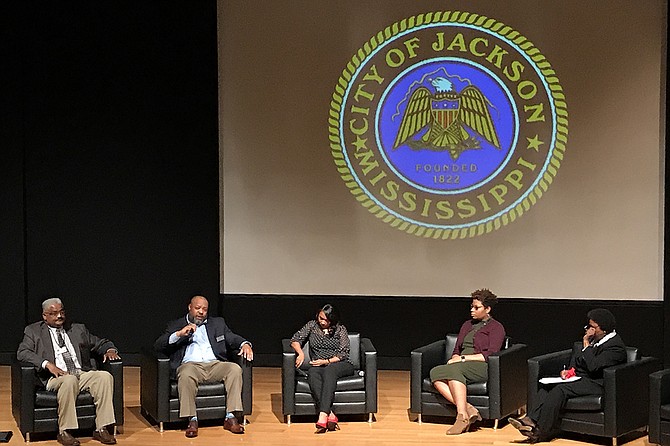

Panelists discussed childhood trauma, re-entry and mental health at the City of Jackson's Crime and Justice Summit at the Jackson Convention Center on April 19, 2018. The panelists were, from left to right, Larry Perry, Devon Loggins, Tiffany Anderson Washington, Fallon Brewster and Etta Morgan. Photo by Ko Bragg

JACKSON — A panel of Mississippi-based professionals sat in black leather armchairs on the stage of the Jackson Convention Center's theater on April 19. Larry Perry, Devon Loggins, Tiffany Anderson-Washington, Fallon Brewster and Etta Morgan were there to lead a panel discussion for the City of Jackson's Crime and Justice Summit.

The conversation went in several directions, but at the core, the panelists and the audience addressed childhood trauma, re-entry services and how to better support victims of crime.

But, some pivotal and controversial crime issues in Jackson were left off the table for the most part, such as officer-involved shootings and Project EJECT, although U.S. Attorney Mike Hurst had come to the summit with his two youngest daughters in tow. He left before the conversation got started, however. He is leading Project EJECT in the capital city under the direction of U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, working with the Jackson Police Department and other agencies.

Some members of the Jackson Police Department briefed the room on this year's crime stats as well as the Interim Chief of Police Anthony Moore's hopes for Jackson in the near future: new police cars, a larger police force and community-oriented policing.

Project EJECT Expels Gun Offenders to Faraway Prisons

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions' Project EJECT is a controversial blast from the past.

"I just want to say that I'm a strong advocate of community policing. It's my goal as chief and for the officers of this department to have a strong partnership with the community and a strong commitment," Moore said.

Then Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba took the microphone, speaking of his brother who is 16 years his senior, who was shot in the head in Jackson in the early 1990s but survived. Referring to himself as a "recovering attorney," the mayor also spoke from the familial perspective, saying he wants a fruitful, honest, productive conversation about the criminal-justice system.

Of Stigma and Trauma

Etta Morgan, a professor of sociology and criminal justice at Jackson State University, served as the moderator. She prefaced the panel's dialogue with a message about stigma.

"I tell my students that you want to talk about a convict as long as it's not in your family," she said. "When it's in your family, you say 'my cousin made a mistake.' Your cousin is also a convict. So don't try to ostracize the person down the street and you have family members with the same issue. We need to embrace and retool those persons in the community."

Devon Loggins, president and CEO of Methodist Children's Homes of Mississippi; Larry Perry, president and CEO of New Way Mississippi, which does reentry work in Jackson; Tiffany Anderson Washington, coordinator of mobile crisis response at Hinds Behavioral Health Services, and Fallon Brewster, Jackson Medical Mall Foundation's VP of marketing and communications joined Morgan on stage.

Loggins, who used to work in prisons, focused on youth trauma. He said that he found that many of the incarcerated people over 18 he worked with had identical backgrounds of trauma as the kids in the Methodist Children's Homes.

"I'm trying to get you to make the connection between childhood trauma, those experiences that kids have no control over whatsoever, abuses that have been perpetrated against them. They're hungry, they don't have anyone," Loggins said.

He added that the anger and poor decisions can result from traumatic events during childhood, such as witnessing or being a victim of violence, which can cause a person to act out or become violent and caught up with law enforcement, Loggins said.

Brewster, who grew up in Georgetown, put the onus on communities having each other's backs, especially when people shy away from therapy.

"When communities feel empowered, and they know each other, and they have those relationships with each other— there's a lot of counseling that can go on amongst the community," she said. "What I've learned was just knowing your neighbors and just understanding what they're going through, you may not be as comfortable going to a counselor, but you can talk to your neighbor...."

Perry, who does re-entry work in Jackson, said the perception of crime in Jackson can be worse than the actual crimes taking place, and that people here spend a lot of time talking about the problem and complaining rather than focusing on solutions.

JPD Assistant Chief James Davis said that he wanted more of the resources on hand that Perry offers because he has had people come to the police department after getting out of prison, asking for things to do so that they will not return there.

"Everybody (doesn't) want to go back to prison, so we have to have that avenue where we can direct them," Davis said to the room.

Needed: Better Police Treatment and Protocol

Then came community voices asking for better treatment and protocol by law enforcement.

Lucinda Wade-Robinson asserted herself to get a chance to speak—she said she had been skipped over as she sat at least eight rows back from the stage. Her son was murdered in Jackson in front of their house as she and other family members sat inside in 2014. She said she and her family were treated horribly by officials, from the police investigator to the Mississippi attorney general's office.

"We were not treated like victims, we were treated like criminals, and the young men that did this, they were treated like they were the victims," Wade-Robinson told the room.

The JFP's 'Preventing Violence' Series

A full archive of the JFP's "Preventing Violence" series, supported by grants from the Solutions Journalism Network. Photo of Zeakyy Harrington by Imani Khayyam.

Wade-Robinson said the only person from the City who had reached out to her was Ward 4 Councilman De'Keither Stamps, leading Mayor Lumumba to interject that it was before his time in office.

The mother who lost her son said she did not want to bash law enforcement, whom she appreciates and even prays for, but that she wants better treatment for the families of victims in the future. She implored the mayor to reach out to the victims of violent crimes as they learn to cope with a lifetime of grief.

"You learn to deal with it but it does not get better—it has not gotten better for me," Wade-Robinson said. "I miss my son more and more every day, and it has not gotten better. And he was murdered over a vehicle ... people mean more than things. He was murdered over a raggedy piece of junk. It was a car that was not running."

"...I feel that things are going to change now that we're under a new mayor. I commend him for what he has done so far," she added.

Email city reporter Ko Bragg at [email protected]. Read the JFP's award-winning "Preventing Violence" archive for crime-prevention solutions.

More stories by this author

- City Wants State’s Help Recouping Funds

- Wise Women: A Mother-Daughter Judicial Legacy Continues

- $1 Million Grant from FTA Will Help City Develop Transportation Corridor

- UPDATED: Former JPD Chief Vance Running Against Beleaguered Hinds County Sheriff

- With 84 Homicides in 2018, City Hopes to Stem Violence With New Cops, Strategy