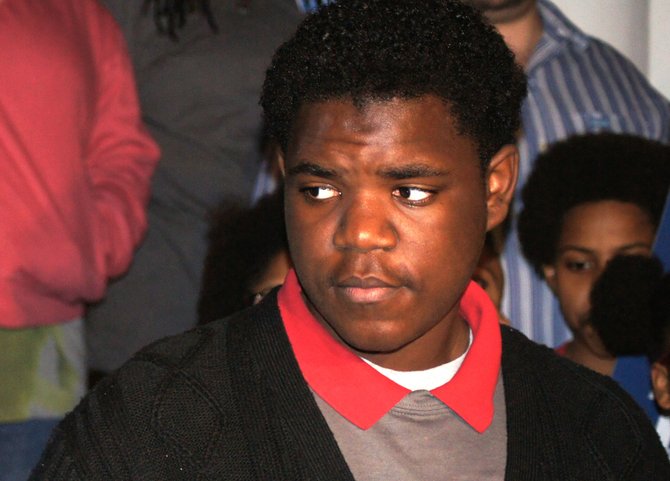

High-school student Donovan Barner calls a proposed curfew ordinance "blasphemous" because enforcing the law requires police officers to assume all teenagers are criminals. Photo by R.L. Nave.

Ineva May-Pittman has lived in Jackson for 66 years. Over the years, she's seen a drastic change in the attitudes of young people and their parents, she said. As kids have grown increasingly ill mannered, May-Pittman believes one answer to the problem could lie with a proposal from Ward 3 Councilwoman LaRita Cooper-Stokes to reinstate a teen curfew.

May-Pittman, who was raised by her single mother after her father's death when she was 10 years old, spoke out at a Nov. 20 public hearing on the curfew ordinance at City Hall. "If we had parents like we had then, we (would not) have a need for a curfew," she said.

Since being elected last spring to fill her husband Kenneth Stokes' old seat, Cooper-Stokes has been trying to reinstitute a city curfew for young people.

But civil-liberties-minded citizens oppose implementing such measures because the laws are often written in a way that can trample constitutional rights.

Bear Atwood, legal director for the Mississippi ACLU, said curfew ordinance could violate citizens' rights to free assembly and speech, and could invite racial profiling. "Curfews do not reduce crime. Curfews don't make our communities safer," Atwood said.

Atwood's assertion flies in the face of the hundreds of municipalities across the U.S. that have put curfews into place and believe the laws keep kids from selling drugs and robbing old ladies.

For example, the U.S. Conference of Mayors conducted a survey in 1997 that revealed 88 percent of city mayors believed that curfews helped make their towns safer.

Kenneth Adams, a researcher at Indiana University - Purdue University - Indianapolis examined the issue in a paper published in 2003 called "The Effectiveness of Juvenile Curfews at Crime Prevention."

Adams examined teen curfews across the county and concluded the scientific evidence "fails to support the argument that curfews reduce crime and criminal victimization."

"Ardent supporters of curfew laws, including numerous police administrators and perhaps much of the general public, likely will resist the conclusion that curfews fail to reduce juvenile crime," Adams wrote. "The seduction of commonsense reasoning sometimes is too strong to be swayed by scientific evidence, which by nature is always open to reconsideration."

Sociologist Mike Males arrived at similar results when he studied teen curfew in Vernon, Conn., in 2000. Males' analysis showed that after Vernon implemented a curfew in 1994, the city experienced a smaller decline in violent crimes than 600 comparably sized cities across the U.S.

According to the abstract of Males' study: "The curfew's main effect was to occupy police time removing law-abiding youth from public, creating emptier, less policed streets, and possibly enhanced opportunities for crime."

Taken together, these analyses seem to speak directly to pro-curfew forces in Jackson, including Kenneth Stokes (now a Hinds County supervisor for District 5), who addressed the public forum and said he frequently observes teens in Jackson's Georgetown neighborhood hanging out late at night, activity he concludes is indicative of hustling or engaging in criminal activity.

Donovan Barner, a student at Murrah High School, lives in Georgetown and said he and friends sometimes take trips to a local store just to get out of the house and clear their minds. "Just because they're out after dark doesn't mean they're criminals," Barner told reporters at a press conference before the hearing took place.

Laurie Roberts, president of the Mississippi chapter of the National Organization for Women, described being a teenage mother who didn't have a car and sometimes had to walk to a nearby store for diapers late at night. Roberts said Stokes' curfew threatens to criminalize young mothers.

The ACLU's Atwood said curfews increase the chances a young person could come into contact with police or be detained. "All the evidence says that even one night in detention could make a big difference in a child's future life. Curfews are an entry into the school-to-prison pipeline," Atwood said.

The lack of jail space has made renewing the Jackson teen curfew a non-starter. Under an old curfew, which expired in 2007, when police picked up violators, they took the minors to Henley-Young Youth Detention Center.

However, state law now prohibits municipalities from holding status offenders, such as curfew violators, in the same facility with felons such as burglars or murderers. A consent decree from the state also prevents the city from creating any new conditions that would send juveniles to Henley-Young.

The Stokeses' answer to the lack of jail space has been to lobby for a new city jail. Kenneth Stokes has lobbied since joining the Board of Supervisors that Hinds County should either jack up the rates it charges for housing Jackson offenders or refuse to accept them, which would force the city to build its own detention center.

Michelle Colon, a community activist who addressed the public hearing, said a new jail isn't the answer either.

"We need to stop incarcerating young people in Jackson and start investing in the youth of Jackson," Colon said.