Anthony Sowell had been out of prison about three years after serving 15 for attempted rape when he ran into Gladys Wade outside a neighborhood store in Cleveland, Ohio, on Dec. 8, 2008. When she said she wouldn't go to his house to drink beer with him, Sowell became emphatic.

He dragged Wade up his driveway, she told The Plain Dealer newspaper in November 2009, hitting, choking and pulling her.

"He hit me so hard. He was dragging me by my shirt, and it was so tight around my neck," Wade said. "I was blacking out and woke up in an upstairs room. He just kept punching me in my face."

Wade fought back. "I kept grabbing at his face and digging into his eyes and his nose," she said. Exhausted, she almost gave up. Then she saw a sliver of outside light through a door. She grabbed at Sowell's crotch and connected. He collapsed, and she crawled out the door.

On the street, the people Wade cried out to ignored her. She ran into a restaurant for help, but the people there didn't want to get involved. Use the pay phone outside, they told her, refusing to call the police.

Sowell followed her, she said. He laughed when he caught up with her in front of the restaurant. "This bitch tried to rob me," he told the men standing outside.

"I just started crying," Wade said. "I was in this circle screaming that this man attacked me, and nobody would hear me."

Wade managed to get away again. She stopped a police car a few blocks away. The officers took her to the hospital, where they stayed with her. "The police at that time took me very seriously," she said.

"They could tell how upset I was."

The next day, 27-year police veteran Det. Georgia Hussein wasn't convinced. "She didn't take me seriously at all," Wade said. "(Sowell) told them that I robbed him and that I assaulted him. And, evidently, his story was somehow more powerful than mine."

Hussein's doubts about Wade's veracity—she had a pending assault case against her—followed the case to the city prosecutor's office, where they dropped her sexual-assault charge. Cleveland police had arrested Sowell, but released him without charges two days later. Wade wasn't a credible witness, the detective indicated to prosecutors.

A year after her attack, Wade found out who Sowell was: a serial rapist and murderer. She was lucky to be alive, one of a handful of women who had escaped him.

Sexual assaults and rape by strangers, though, are a small fraction of all rapes in America—only around 5 percent. Most victims know their attackers.

Sometimes, they're married to them.

Zero Physical Findings

The most important thing an attack victim can do after a sexual assault or rape—whether she or he has any intention to report the crime to authorities—is to go to an emergency room. There, nurses will conduct an exhaustive examination that includes taking samples and will administer prophylactic medications to guard against sexually transmitted disease and pregnancy.

Technically, sexual assault includes any unwanted sexual contact, including fondling and molestation.

Most experts define rape as the most severe type of sexual assault; rape is unwanted penetration, whether vaginal, oral or anal.

"When a person is sexually assaulted ... we tell them to, first and foremost, seek medical attention," said Shalotta Sharp of the Mississippi Coalition Against Sexual Assault, who is also a certified sexual assault nurse examiner, or SANE nurse, for both adults and children.

Rape-crisis advocates play a vital role in helping victims through the process. A good advocate will explain the reasons the procedures are necessary, help her through invasive exams, even provide clothing to replace the garments the hospital will retain for forensic testing and, possibly as evidence in a trial. The law imposes no statute of limitations for sexual-assault crimes; even if a victim does not file charges immediately, the samples can still support a rape charge even years later.

Trained SANE nurses and advocates can alert hospital security to prevent a perpetrator from contacting the victim, and also guide victims toward counseling to ease or prevent rape trauma syndrome or its more serious psychological cousin: post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Counseling is crucial, Sharp said, and about half of all rape victims are subject to PTSD. When a victim doesn't seek help and can't resolve her feelings about the rape, she can experience a stress reaction dubbed "silent rape syndrome."

Depression, suicidal behavior, panic attacks and acting out—whether through alcohol and drug abuse or promiscuity—are key behaviors associated with the syndromes.

"Victims, they will self-doubt; they will talk themselves out of this being an actual sexual assault," Sharp said.

"What is sad is that, psychologically, they will deal with this later. One way or another, they're going to deal with it. Their heart is broken; their spirit is broken."

The rape exam is lengthy and can be difficult, especially for an already traumatized victim. Many of the questions are extremely personal (such as, have you had sex within the past five days, and if so, was it vaginal, anal or oral?), and the woman or man will have to relate the assault in excruciating detail. But it's necessary, even cathartic, for victims.

"That rape-crisis advocate is the second-most important person in that victim's life at that particular time," Sharp said, adding that the first is a trained nurse.

"The only reason medical staff is the most important is because that medical staff is trained to get advocacy there for that victim."

A trained advocate can help the victim through the procedure. "We're asking that person to recount the most traumatic thing that's ever happened to them, so we do that compassionately. We allow the victim to set the pace, allow them to take their time in giving us that history," Sharp said.

Although the exam can be stressful, victims generally understand its importance.

"When we explain everything that we're doing and the nurse explains why we're gathering this information, it gives them the satisfaction of knowing that somebody is working hard on their behalf," Sharp said.

"In the years that I've done this—and I've seen hundreds and hundreds of victims—I can probably count on one hand the victims that have said, 'That's too involved; I don't want to go through this.'"

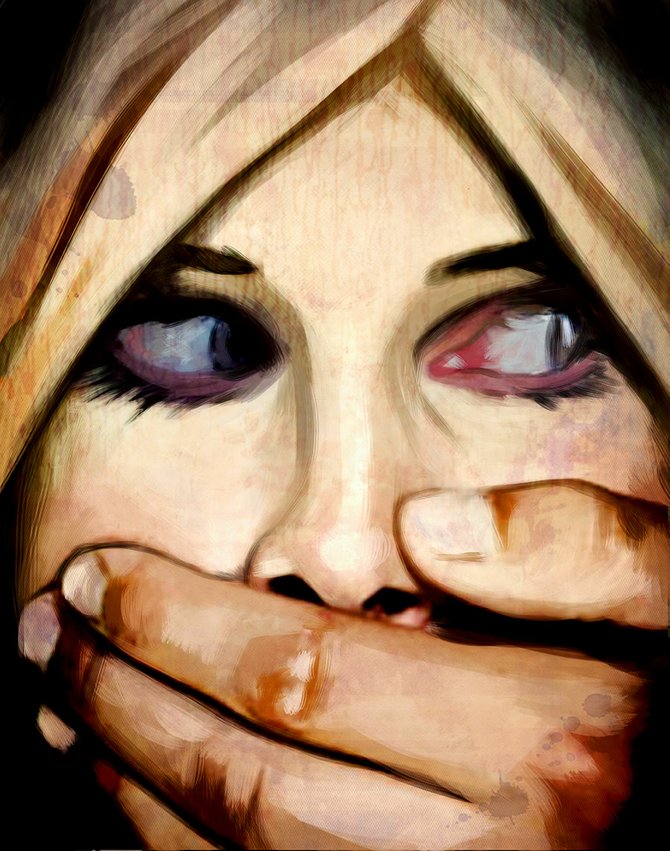

One of the key jobs that organizations such as MCASA do is to educate medical personnel, law enforcement and members of the judicial system about the realities of rape. The ubiquitous image of a rape victim—disheveled, beaten and hysterical—promotes an unrealistic picture. Some don't even cry. They may be reluctant to disclose details, or may lie about drug or alcohol use. They can be confused or have memory lapses.

"It's frustrating, because TV and the media have portrayed a rape victim as having horrible physical injuries, and that's not necessarily the case," Sharp said.

"... The body protects itself against this type of trauma. ... Ninety-six percent of our patients have zero physical findings."

A woman's vagina will lubricate, for example, reducing or eliminating pain and injury. One of the most disturbing aspects for some victims is if they become sexually aroused or have an orgasm in the course of a rape—especially for men, but it happens to women, too. It's a natural, physiological reaction to genital stimulus, Sharp said, and a rape victim has no control over it. It does confuse victims who believe that a sexual response should only occur during pleasurable sex, and it tends to add shame to the incident. A correctly completed rape exam, however, can reveal damage not visible to the naked eye.

This is vital, because lack of obvious physical trauma can lead police—and juries—to doubt that a rape actually took place.

No 'Perfect' Victims

Paula Broome, special assistant attorney general and violence against women resource prosecutor in the Mississippi attorney general's office, said that it's rare to have a "perfect" victim. In a training presentation for rape crises advocates, Broome indicated that proof of penetration, DNA matches and witnesses who heard screaming are all "wishful thinking," in a typical rape case.

More likely, she wrote, a victim suffered minimal physical injury. She may have had a few too many drinks or, perhaps, he may have flirted with his attacker. An adult victim probably has had sex at some time in his or her past, perhaps with multiple partners.

The victim might even be a prostitute and her rapist a senator's son.

Victims, of course, aren't immune to the myths, either. In the absence of physical trauma, they may doubt whether a rape occurred at all; they will delay or fail to report the incident. Instinctively, many will shower or bathe after the attack and before going to a hospital. Even if it makes prosecution more difficult, all of that is normal behavior, and law enforcement, medical personnel and ordinary citizens that make up juries should be educated to understand that.

What isn't normal is that if victims don't have health insurance, they might also be afraid of incurring a big medical bill. But cost should be the last consideration for victims seeking help. If Mississippi is doing something right, Sharp said, it's that the attorney general's office will reimburse hospitals for completing a rape kit, if necessary. While many states provide no reimbursement and others pay a pittance, Mississippi will pay up to $1,000 so that the victims don't have to bear the cost.

"I'm so proud of Mississippi for this," Sharp said. "I can't shout it enough."

Women as Property

Gladys Wade's experience with police and prosecutors—men and women charged with protecting her—is all too common.

"One of the biggest fears ... is that you won't be believed," said Michele Alexandre, an associate law professor at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. "Then you proceed to blame yourself and have society blaming you. It's very hard to recover from that."

Most rape and sexual-assault victims never file reports against their attackers; estimates run from 55 percent to as high as 85 percent. Even when victims file reports, the crimes carry notoriously low arrest and conviction rates. Only about four to six out of every 1,000 rapists in America will ever serve time in prison.

The reasons behind the statistics are complex and confounding: Laws are archaic, prosecutors are hesitant to pursue cases they believe are unwinnable, victims are afraid no one will believe them, support systems are threadbare.

"I think we have failed victims of sexual violence," Sharp said. "We have failed them because we've not done a good job educating other people in this field such as law enforcement, such as other medical staff."

Both men and women frequently feel fear, shame and guilt after an attack, leading them to keep silent. Victims may believe that because they were drinking or because they dressed to attract attention, it makes the attack their fault. They might think that it's the man's right to take what he wants. Some are afraid of retaliation or ridicule.

You don't have to look far to see how endemic the problem is in America. The news is full of it, from priests abusing altar boys, to coaches assaulting young athletes, to politicians and yoga gurus using their power to "seduce" their victims.

Still, "she was asking for it," and "serves her right," are typical responses to these horrendous, violent crimes. We live in an age when objectifying women and reducing them to body parts is commonplace. Catch an episode of Oxygen's "Bad Girls Club," or ask any woman who been the object of catcalls on the street or harassment in public. "Check that thing." "Shake that booty." "Great tits."

Where do those attitudes come from, and how is it that in 2012, people still blame victims over perpetrators for domestic violence and sexual-assault crimes?

It begins with the learned biases that are ingrained in our laws, Alexandre said. Inherent in our attitudes about rape is the idea that a woman's body is a commodity; it doesn't belong to her, and it can be appropriated.

Once a woman engages in consensual sex or engages in sensual behavior—whether it's wearing short skirts or using suggestive language—people, and juries, assume that somehow she consented to her own rape. It's that faulty thinking that has people saying things like, "If she didn't want to be raped, why did she dress that way?"

"Consent—because our body is susceptible to being appropriated—is not ours," Alexandre said. "We give our consent implicitly."

Perhaps unconsciously, legislators based rape statues on societal standards set in times when females were chattel, possessions of their husbands and fathers, and marriages were monetary or political transactions. Suitors paid fathers a "bride price," and husbands assumed ownership of "their" women.

Laws mandated that rapists pay a reduced bride-price to fathers of unmarried daughters, and in some places, the victims had to marry their attackers.

Typically, virginity raised a woman's value. In ancient times, people gave virgins spiritual significance; they warded off evil spirits, caused crops to flourish and channeled divine blessings. Magically, a woman whose hymen was broken lost those extraordinary powers; she also lost her ability to accuse an attacker.

The Code of Hammurabi, written around 1780 B.C.E., states that if a betrothed virgin is raped, she is considered blameless and her rapist should be put to death.

If, however, she is married, she and her attacker should both die.

Ancient history, perhaps, but those attitudes still permeate our culture. Women haven't had the vote in the United States for 100 years, yet, and many couldn't own property until 1900. Mississippi became the first state to allow married women to own property in 1839 to allow widows to keep their husbands slaves, but it took another 70 years for all states to allow women to inherit and own property. Until the 1970s, single women were generally denied the ability to buy property or get credit in their own name.

In America, Alexandre said, race further complicates the issue. In "Girls Gone Wild and Rape Law," published in the Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law in 2009, she pinpointed one of the fears encapsulated in the law: false accusations.

"False rape claims by white women against black men as well as the United States' violent racial history of lynching have strengthened (that) fear," she wrote. "The reality for many women of color has been that, along with being raped and treated as a commodity, women of color historically have lived in fear of losing their fathers and husbands to the slaughter that traditionally followed accusations of rape ... during slavery and the Jim Crow era." Those fears, she indicated, have perpetuated generations-old teachings to keep women victims silent.

The laws defining consent are also tied to the idea of force.

"If the idea of consent is a sexual interaction obtained through force, it implies that a woman who does not fight back cannot be raped," Alexandre said. "How much force is necessary is often influenced by the notion that, sometimes, 'No' can mean 'Yes.'"

"So even if the woman protests or says no or even fights back in some way, she might not have fought back hard enough," Alexandre said.

Mississippi's rape and sexual-assault statute, as elsewhere in the U.S., include force as a defining factor, making it "one of the most regressive, one of the most conservative," Alexandre explained.

Shielding the Victim

"When you're talking about the rape of an adult, we're going to have to show that it was forcible or against the will of the victim," said Michael Guest, district attorney for Rankin and Madison counties.

Mississippi, like every state in the union, has adopted a rape shield law to prevent a rapist from using his victim's past as a defense.

"Generally, the law does not allow the defendant to go in and put the victim on trial, talk about prior instances of sexual conduct that may have occurred, either between themselves or with other individuals," Guest said.

"But sometimes that can come into play if the victim's credibility is attacked. ... Sometimes the court can allow that type of information in."

Prosecutors work hard to keep that kind of evidence away from jurors. "At least in our district, our judges are good at following the law and not allowing that in," Guest said, but that's not always the way it happens.

"(The defense) may make (a woman's character or her past) applicable to the case, and a judge may find that, based on the defense's theory of the case, that (it) is somehow admissible. Because a defendant, they have the right to present their theory of the case," he said, regardless of whether that theory makes a lot of sense.

It's not easy to get a victim's past into a rape trial, but a judge's opinion can supersede the rules of evidence. "Ultimately, it's going to come down to the person wearing the robe,' Guest said. "They're going to do their best to make sure that they make the right ruling. They want to get it right. They don't want to be overturned or reversed later on. They're going to make sure what they believe is the right decision."

When a jury hears evidence impugning a victim's character and hears story about her past sexual behavior, the case is no longer about consent or force.

Now, the victim is on trial.

"We put a lot of onus on women to actually be pure as the driven snow," Alexandre said. Evidence about a woman's prior sexual history "creates a narrative about the victim that is hard to surmount." Once a defendant creates doubt that the victim isn't as pristine as a jury would like her to be—which means she has had no sexual experiences, either with someone else, or especially the defendant—it becomes very hard to prosecute a rape case.

"A lot of judges are swayed by this issue of credibility," Alexandre said. "They are convinced too readily that the jury needs to hear (about the victims) prior experiences when the rape shield statutes really make it clear that unless it's absolutely necessary, you should not introduce this kind of evidence."

Judges must also give clearer jury instructions, including pointing out our learned, ingrained biases against rape victims. Alexandre pointed out that those biases mean that the fight can't be won in court, alone. We have to teach children at a very young age what consent actually means—that it's not alright to push, and "No" really does means "No."

"We have to erase the damage we've done," with thousands of years of laws and attitudes about women and their ability to consent—or not to consent, she said.

"Consent is on a continuum. A woman can withdraw it at any time."

But in a state that can barely talk about sex at all, educating children to have respect for consent is a tall wall to get over.

"Mississippi has some challenges because of the reluctance to deal with sex education," Alexandre said.

"We have to start with that."

Fixing What's Broken

The barriers to lowering rates of rape and putting rapists behind bars in Mississippi are numerous, but solutions are available. Whether anti-rape advocates come at the problem through the law or increased victim assistance, one substantial problem still exists: Mississippi doesn't have enough advocates working for change.

Of the roughly 120 hospitals in the state with emergency rooms—the facilities that the MCASA's Sharp targets for medical personnel trainings—few have adequate numbers of nurses trained to care effectively for victims. Some don't have any. Some rural areas don't have emergency facilities, and the state has too few rape crisis centers that can dispatch people to help victims through the process of gathering samples or to assist them in navigating often-hostile legal proceedings.

"Our goal is that every hospital have a group of advocates they can call on and have someone on staff that has been trained ... on how to assess that patient and how to collect that evidence," Sharp said.

"But no, we don't have nearly enough people trained in Mississippi. ... We have half or less than half of what we need."

Another part of the problem is that no one really knows the extent of rape and sexual assault.

Many experts rely on the FBI's Uniform Crime Statistics data, compiled from voluntarily reported numbers from various law-enforcement agencies nationwide. Those numbers only reflect rapes that women report to police, which may be as low as 15 percent. The FBI doesn't investigate their accuracy.

Male rapes are not included, and rape reporting is subject to hierarchy rules, which codify that if another crime also occurred (homicide, for example), the FBI only counts the more serious charge. Nationwide in 2010, UCR numbers show 84,767 rapes, down from 88,097 in the previous year; in Mississippi, the reported numbers are 927 rapes in 2010, down from 991 in 2009.

In 2003, the Charleston, S.C.-based National Violence Against Women Prevention Research Center estimated that one in every nine Mississippi women had been victims of rape. The report, aptly titled "One in Nine," stated that the number exceeded 127,000. That's a conservative number, the report states, based on the scant available research at the time. The number did not include attempted rape, alcohol or drug-facilitated rape, incapacitated rape—where the victim may have been mentally ill, elderly or otherwise incapable of consent—or statutory rape of minors. The estimate also doesn't include males.

The numbers are probably much higher. Last December, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the results of its National Intimate Partner and Violence Survey, conducted in 2010. The numbers of American women who are victims of rape are closer to 1.3 million annually, the report concluded, and nearly one in five women has been raped in her lifetime. Mississippi was among a handful of states that did not participate in the survey.

But regardless what the numbers show, the fact remains that victims have too few effective, compassionate people on their side. Rape is not about sex any more than domestic violence is about love, said Sandy Middleton, executive director of the Center for Violence Prevention in Pearl.

People must realize that it is an act of violent aggression, and that victims are not to blame. Rape is the ultimate expression of power and control that a perpetrator can force on his victim. As long as victims don't trust that they will be cared for, as long as laws are inadequate and the prevailing myths about rape continue to fester, victims will remain silent.

"Victims go through a lot in these cases," Guest said. Rape kits are not fun, but he emphasized their importance by adding that if a woman has not been assaulted, it's unlikely she would put herself through such a stressful experience.

"Every victim of sexual violence has the right to the care that they want, and nobody should stand in the way of that—family members, friends, medical professionals—nobody should stand in the way of that victim," Sharp said. "They are to be believed."

House of Horrors

In Cleveland, Ohio, nearly 11 months after Gladys Wade reported Anthony Sowell's attack, police went to Sowell's house at 12205 Imperial Ave. On Oct. 29, 2009, with an arrest warrant for rape. Another woman had accused him of hitting, strangling and raping her the month before.

Sowell wasn't there, but when they entered the house, police found two women's corpses in the living room. By the time forensic experts left the scene a couple of weeks later, the body count for the "Cleveland Strangler" had risen to 11. Investigators found bodies stuffed into crawl spaces and buried in his yard and basement.

Police arrested Sowell Oct. 31, 2009. Charged with 11 counts of rape and murder, a jury convicted him in August 2011, and Cuyahoga County Judge Dick Ambrose sentenced Sowell to death. Officials believe he may be responsible for other, unsolved cases.

East Cleveland police reopened similar cold cases to investigate possible connections to Sowell, and the FBI began an investigation into similar crimes in other places were he had lived.

Cleveland demolished Sowell's "house of horrors" in December 2011, three years, almost to the day, after Wade's escape. Six of the raped and murdered women died after her attack in 2008.

When she heard about the other victims, Wade felt guilty that she hadn't done more to convince police, the Plain Dealer reported. "I kept thinking of all those families," she said. "All those women that might be alive if these people had only believed me."

Help the Center for Violence Prevention start a rape-crisis center. See http://www.jfpchickball.com for several ways to help and follow on @JFPChickball.

Related Stories

Intent to Ravish

Does Jackson Need Another Rape-Crisis Center?