Almost immediately after his appointment to U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi in late 2001, Dunnica Lampton began to investigate key Mississippi Democrats.

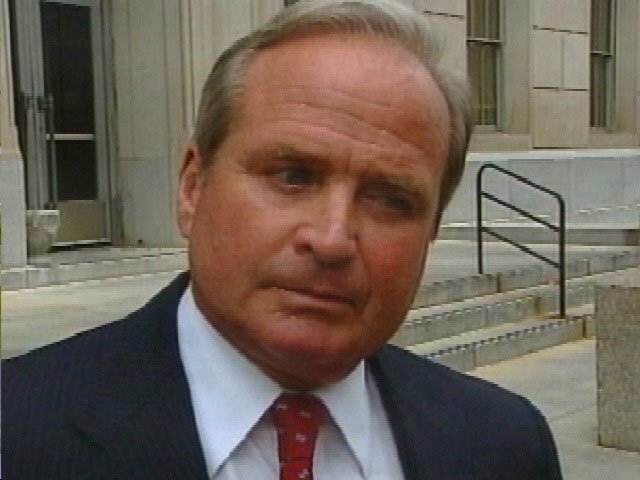

Trial lawyer and major Democratic campaign contributor Paul Minor quickly became a target of such an investigation. On July 25, 2003, three months before the Mississippi gubernatorial election, a jury indicted Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Oliver Diaz Jr., Paul Minor, former Chancery Court Judge Wes Teel and former Circuit Court Judge John Whitfield on charges of bribery. The charges related to loan guarantees that Minor had made to the three judges to help defray campaign costs.

No state law prohibited Minor's contributions, and his trial resulted in an acquittal on some charges and a deadlocked jury on others. However, immediately following that trial, Lampton brought new charges.

During the second trial, presiding Judge Henry Wingate excluded evidence that showed Minor had a long-established pattern of offering loans or loan guarantees to many friends in the legal community, thus creating the appearance that Minor had helped the three judges in hopes of receiving something in return.

Although prosecutors were unable to prove that Minor had bribed the judges in exchange for favors, the second trial resulted in a conviction. Minor was sentenced to serve an 11-year prison term and pay more than $4 million in fines and restitution.

As in the case of former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelmanalso targeted by a Bush-appointed U.S. attorneyMinor has been denied appeal bond. Both Siegelman and Minor, despite being convicted of white-collar, non-violent crimes, were shackled and manacled, and moved to out-of-state prisons.

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals has since released Siegelman as he appeals his case.

Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Oliver Diaz, who himself was indicted and acquitted twice in the Minor case, has asserted that the defendants were presumed guilty from the start. "An individual was singled out for examination from the federal government, and prosecutors then attempted to make his conduct fit into some criminal statute," Diaz said. "This is not how our system of justice is supposed to operate."

The Beginning: Big Tobacco

The tortuous trail to Paul Minor's jailing begins in the 1990s, with the set of history-making cases that several states brought against the tobacco industry seeking to recover smoking-related health costs. Minor was among those representing the plaintiffs, along with other trial lawyers and state attorneys general, including Mississippi Attorney General Mike Moore.

The tobacco industry settled without going to trial, paying $246 billion to the states in the largest civil settlement in history. Among those forced to pay were the four largest tobacco companies: R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., Lorillard Tobacco Company and Philip Morris USA.

Trial lawyers like Minor earned millions from the deal, and many became generous contributors to Democratic candidates and campaigns, especially in the South.

In 1999, Mississippi trial lawyers donated as much to Democratic gubernatorial candidate Ronnie Musgrove as did the Democratic National Committee. Musgrove received $379,500 from trial attorneys, of which Minor donated $112,000. Minor and his law firm donated hundreds of thousands to Democratic candidates between 2001 and 2004, including, according to the New York Times, $129,000 to then-presidential contender John Edwards.

The tobacco settlement, however, had serious repercussions for the integrity of U.S. elections.

Mississippi attorneys have described the behind-the-scenes political fight sparked by the tobacco ruling as nothing short of "war"between corporations and Republicans on one side and plaintiffs, trial attorneys and Democrats on the other.

Attorney Lance Stevens, president of the Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association in 2000 and 2001, said he saw the attacks on plaintiff attorneys in the years leading up to the state's tort reform overhaul in 2002 and 2004. He said he believes the attacks were indisputably backed by big money.

"There is a war going on, and (the 2002 and 2004) state tort-reform laws were the end result of it; but I think it was more the confluence of the tobacco settlement and the judgments against Big Pharma over drugs that killed a lot of people that really started it," Stevens said.

"If you pool the tobacco folks and the pharma people, you've got an incredible amount of money and power, comparable to the old railroad barons of the past, with Haley Barbour acting as Boss Hogg."

During the early years of the Bush tenure, some inside the Republican National Committee allegedly saw Minor as an obstacle to their new southern strategy.

As one Mississippi attorney explained: "In war, you first cut off the supply lines of the enemy troops." Minor was the supply target because of his large donations to Democratic candidates. Judge Oliver Diaz was the obstacle to corporate interests seeking to reduce plaintiff cases and keep tribal casinos deregulated.

Rove, Tort Reform and Big Tobacco

Republican attorney turned whistle-blower Dana Jill Simpson has alleged that Karl Rove, the former Bush adviser, played a major role in the prosecution of Don Siegelman in Alabama. Simpson is not alone in her allegations. Many lawyers, politicians and even active members of the Alabama RNC have made similar allegations during the course of our investigation.

As one Alabama Republican close to the state GOP said, Rove "would never discuss anything on the phone. He would tell you to meet him at some corner, and then you get there and sure enough, he is standing in the middle of the intersection waving at you."

The House Judiciary Committee has subpoenaed Rove to testify about his alleged role in the prosecutions in Mississippi and Alabama. Through his lawyer, Robert Luskin, Rove has repeatedly stated that he wants to testify privately to the House Judiciary Committee, that he will not testify under oath and that he wants there to be no transcript of his testimony. Rove has been evasive when asked publicly if he was involved in the Siegelman prosecution.

But Rove's role in the U.S. attorney scandal is one that he has played for many years, acting as a broker on deals, which were rewarded by corporate donations to Republican coffers.

"Rove is a lobbyist," said one Washington source close to the investigation of convicted lobbyist Jack Abramoff. "He never stopped being a lobbyist."

Rove met frequently in 2002-03 with Abramoff, other lobbyists and Alabama campaign operativesspecifically with members of Bob Riley's gubernatorial campaign. Riley was Don Siegelman's Republican opponent, and Riley's campaign adviser, Bill Canary, was Karl Rove's long-time business associate. Moreover, George W. Bush appointed Bill Canary's wife, Leura, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, and it is her office that prosecuted Siegelman.

Ten years before the tobacco settlement, in 1988, Rove had already discovered the advantages of appealing to both voters and corporate donors by painting trial lawyers who had won generous settlements in cases of corporate negligence or medical malpractice as greedy corruptors of the judicial process.

With Rove's encouragement, the "tort reform" movement, aimed at limiting damage settlements, developed rapidly through the 1990s, pulling in corporate contributions and twice helping Rove elect George W. Bush governor of Texas.

Rove also served as a consultant for tobacco giant Philip Morris, which invested heavily in Texas judicial races, helping to secure Republican dominance in that state's courts by the end of the decade. An internal 1995 Philip Morris document from 1995 indicates just how involved Big Tobacco was in creating the "Tort Reform Project," although there is no evidence tying Rove directly to that strategy.

Rove even did his best to head off Texas's participation in the state lawsuits against the tobacco industry. "From 1991 through 1996, while guiding the ascent of Bush to the Texas governorship and during his early years in that office, Rove worked as a $3,000-a-month consultant to Philip Morris," Salon's Sidney Blumenthal wrote last year. "In 1996, when Texas Attorney General Dan Morales filed a suit against tobacco companies seeking compensation for state Medicaid funds spent on workers who fell ill because of smoking, Rove conducted a dirty trick against hima push poll spreading smears about him."

In 1994, Rove brought his "tort reform" strategy to Alabama, where he worked with GOP operative and lobbyist Bill Canary to elect Republican judges. There, he also had his first run-ins with then-Lt. Gov. Siegelman. Alabama's Republican Attorney General, William Pryorwhose 1998 re-election campaign was managed by Rovewas one of the few state attorneys general who attempted to keep their states out of the tobacco lawsuits and was, as a result, sharply criticized by Siegelman.

It was Pryor who in early 1999 began the investigations of newly-elected Gov. Siegelman, which eventually led to his bribery conviction. Canary's wife, Leura, would federalize the investigation almost immediately after she was appointed U.S. attorney.

Pryor also co-founded the Republican Attorneys General Association, which received money from firms like Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds to help elect pro-corporate candidates. The association received a warm welcome in Texas from Rove.

As a result of tobacco lawsuits, some Republican politicians and tobacco industry lobbyistssuch as now-Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbourappear to have become implacable foes of the trial lawyers who had frustrated them and their clients. Barbour returned to lobbying in 1997, after a four-year stint heading the Republican National Committee, and became one of the main lobbyists for Phillip Morris, which spent nearly $16 million that year in lobbying fees.

Although Barbour's firm failed to disclose many of its financial records from that time, the lobbying fees that the firm reported in 1997 show that Barbour Griffith & Rogers received $1.7 million from all four major tobacco companies.

In 1997, Barbour even attempted to sneak a $50 billion tax break for the tobacco companies into a balanced-budget agreement, with the help of Newt Gingrich and Mississippi's then-Sen. Trent Lott, a plan that was only thwarted at the last moment.

Purchasing the Law

In Alabama, the corporate client was the gambling industry. Its lobbyist was the now-convicted felon Jack Abramoff, who brokered deals and funneled money to Republican congressional coffers. Although the money came in from neighboring Mississippi, the issue for Abramoff's gambling clients was a proposed state lottery that Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman was promoting. The gambling industry flooded Republican coffers in exchange for other types of favors, such as the loosening of gambling industry oversight.

In Mississippi, the corporate client was Big Tobacco, and their lobbyist now sits in the governor's chair.

The second aspect of the strategy is the politicization of U.S. law enforcement by the Bush administration, specifically the Department of Justice. The U.S. attorney scandal is less about the U.S. attorneys who were fired than about those who remained and are alleged to have used federal law enforcement resources to intimidate Democratic campaign donors.

The demonizing of Democratic candidates helped both the Riley campaign in Alabama and the Barbour campaign in Mississippi. Until these prosecutions, Democratic governors led both states.

In addition, by targeting Minor, Barbour and his backers ensured a glacial freeze in contributions to Democratic candidates, because other trial lawyers were afraid that the U.S. attorney's office would target them as well.

Barbour won the 2003 governor's race by a narrow margin, defeating Democratic incumbent Ronnie Musgrove and becoming only the second Republican governor of Mississippi since Reconstruction.

Securing the Governorship

However, the forces that led to Barbour's victory were already on the move more than a year earlier, well before Barbour announced his candidacy.

On Nov. 21, 2002 , UPI reported that the Republican Party was making a special effort to target Musgrove in the 2003 election and that Barbour was widely expected to be the challenger.

"Barbour would be a powerful opponent," UPI wrote. "He has a national network of potential contributors and a close relationship with the GOP's No. 1 campaign asset, President George W. Bush."

That summer, the Mississippi Legislature had begun holding hearings on whether to enact tort reformthe strategy that the tobacco industry promoted to limit settlements to plaintiffs, which Rove had used to defeat Democratic judges in both Texas and Alabama and pass pro-corporate legislation.

A few months later, Mississippi newspapers began to print leaked allegations that the FBI had launched an investigation of Paul Minora leading opponent of tort reformon suspicion of having bribed several judges. David Baria, then-president of the Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association, described the timing as "very interesting," according to an October 2002 Associated Press article.

According to the same article, Bush-appointed U.S. Attorney Lampton, who was leading the investigation, had ties to Republican politicians who favored of the tort reform plan that the tobacco industry supported.

Lampton also had conflicts of interest, among the most egregious of which was that at the time of his investigation, Minor was in the process of filing a lawsuit on behalf of plaintiffs against Ergon Inc., a company run by Lampton family members.

After stories about the investigation of Minor appeared, Barbour, who formally announced his candidacy for governor of Mississippi on Feb. 17, 2003, began using these press accounts as a talking point against his Democratic opponent, incumbent Gov. Musgrove.

In fall 2002, additional allegations allegedly leaked from within the DOJ had begun to appear that Musgrove had also been taking bribes from Minor.

In November, for example, The Clarion-Ledger reported that Musgrove was "under scrutiny" for campaign contributions he had received, including $27,125 that came from Paul Minor a month before Musgrove appointed an associate of Minor's to the Mississippi Court of Appeals.

Barbour used both the rumored FBI investigation into Musgrove, which never materialized, and Minor's donations to the Musgrove campaign as a tool to bludgeon his political opponents.

He painted Musgrove, as corrupt, using the federal investigation as proof of these claims.

Minor's conviction has also provided the GOP with a political weapon that can be used over and over. The National Republican Senatorial Committee, for example, is using the Minor conviction as a political tool against Musgrove, who is now running for former Mississippi Sen. Trent Lott's seat in the U.S. Senate.

Almost immediately after Barbour took office in 2004, he called a special session of the Legislature to ban class-action lawsuits and cap damages in almost all tort cases. In 2006, Barbour won a lengthy court battle to completely withdraw funding from an anti-smoking program, which had been successful in reducing smoking among middle-school and high-school students.

Larisa Alexandrovna is the managing editor of investigative news for Raw Story and regularly reports on intelligence and national security matters. Contact her at [e-mail missing].

Muriel Kane is the research director for Raw Story Investigates.

Additional reporting by Adam Lynch of the JFP.