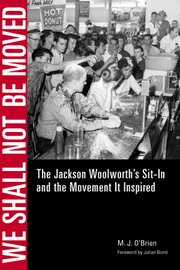

John Salter, a social science professor at Tougaloo College, sat with his students Anne Moody, Pearlena Lewis and Memphis Norman--a white man and three black students--at the "Whites Only" counter in Woolworth's store lunch counter. Nobody would serve them. Behind them was a growing crowd of frenzied onlookers, police officers and news people. It was 11:15 a.m. on May 28, 1963.

Bill Minor, then a reporter for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, was there that day. He was the Mississippi correspondent covering civil rights events in Jackson and the state. Minor, tipped off by Medgar Evers, gathered with the other news people at the planned sit-in and watched the scene unfold.

"The people working behind the counter at Woolworth's were afraid to serve anybody," Minor says. "They just let them sit there. They wouldn't serve them. That's what they were ordered to do--not serve any blacks."

Some people wanted no trouble and left the counter, leaving them alone. After the students sat for a while, the crowd began to taunt them. They wanted the "n*ggers"--both white and black--to leave. By noon, high school students from Central High School (since disbanded, now the Department of Education building) came inside on their lunch hour, looking for action. Soon the space was filled with an anxious crowd, whipping themselves up. A mob was forming.

The verbal abuse escalated to physical altercations. People poured mustard and ketchup on the heads of John, Anne, Pearlena and Memphis. Another (white) student from Tougaloo, Joan Trumpauer (now Mulholland) stood outside as a look-out for any counter-protesters. Inside, people kept pouring the condiments on their heads.

Police officers watched the events unfold but did nothing.

In a quick burst, someone pulled Memphis Norman off his stool and threw him to the ground.

"These white thugs began kicking him in the face right there on the floor," Minor recalls.

Blood fell from Norman's mouth. The other students remained seated.

"The police officers were inside of the store watching the whole thing, just a few feet away while these thugs were kicking this young black guy," Minor says. "Kicking him in the face, and they did nothing to restrain them. They let it go on for a good while. Finally, they broke it up." The police officers arrested Norman and someone who attacked him.

Anne was pulled from her seat, as was Pearlena, but they were not struck, and they fought their way back to the counter. By this time, Lois Chaffee, a white faculty member at Tougaloo, and Joan Trumpauer took seats at the counter.

John Salter was struck down by a punch, leaving Anne, Pearlena, Joan and Lois--two blacks, two whites--at the counter. Their bodies were smeared with dried ketchup, mustard, sugar, anything that was on the counter. They sat and faced the front.

Minor recalls covering the event, unable to help or interfere. "Being a newsman--even though it might tear your heart out," Minor says, "you can't get involved."

They sat at the counter for hours. Finally, the manager of the store closed it down. It was finally time to leave, but it was hard to leave--there was a crowd outside, too. No police officer would escort them out, so the president of Tougaloo College, Dr. A. D. Beittel, who arrived after he heard what was going on, led the students out of Woolworth's.

Years later, Anne Moody went on to write in her autobiography "Coming of Age In Mississippi": "When we got outside, the policemen formed a single line that blocked the mob from us. However, they were allowed to throw at us everything they had collected."

The four were taken to the NAACP headquarters on Lynch Street.

Moody also wrote that, later that night, a huge meeting of people gathered to organize more demonstrations. Medgar Evers told the crowd that the Woolworth sit-in was just the beginning, a continuation of the ones held in North Carolina, Tennessee and Florida, and was a precursor to what was coming; Jackson would be a place to take a stand. Evers was shot in the back and died in his driveway three weeks later.

Demonstrations similar to the Woolworth sit-in in Jackson occurred, but Bill Minor says Woolworth was "the signature event of the protest movement in Jackson. The first one there was with real violence."

The next year, in 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed into law.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the sit-in, the city of Jackson will unveil a marker for the event on the Civil Rights Trail May 28. The event starts at 10 a.m. on Capitol Street. The city of Jackson will also commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of Medgar Evers throughout the month of May and the beginning of June. Call 601-979-2055 for more information on the Woolworth trail marker unveiling.

Comments