With a skinny tie and sassafras root 'round his neck, Seth Ballard Sr., the last of the Mississippi Herb Doctors, looks out serenely from a photograph on page 37. On page 55, a waitress in a starched white dress smirks coyly into the camera as she mimics taking the order of a customer at Steven's Kitchen.

These are just a few of the colorful characters included in Turry Flucker and Phoenix Savage's new book, "African Americans of Jackson" (Arcadia, 2008, $19.99). The 125-page pictorial history of Jackson's African American community is part of the "Images of America" series, and is much more a scrapbook for than a history of the community.

After a brief introduction that concisely sets up the chronology of the community, six chapters of vintage photographs and captions tell the religious, economic, social and political history of Jackson's African Americans from the 1830s until the 1970s. Chapters such as "Going to Meeting" and "More than Just Getting By" showcase specific churches and long-closed businesses to contextualize the community with tenderness, intelligence and pride. "Freedom Now" documents Jackson's contributions to the Civil Rights Movement, including Duke Ellington's concert at Tougaloo College the night Medgar Evers was murdered. The last section, "Blues Expressions," focuses on the art and culture of the community, with an emphasis on Jackson State University's and Tougaloo College's contributions.

To be eligible for inclusion in the "Images of America" series, the book could only include vintage photographs, which is why the book does not continue up to the present. It ends with an upbeat image of youth and power from the mid-1970s as three youngsters with set jaws and raised fists display their "Save Farish St." sign.

In May, Savage explained that she and Flucker wrote the book to "give back" to the community. "We hoped that people would see images that they would recognize and we (made) sure there was attention to un-identified people," Savage said in a telephone interview. Many photographs appear without identification which, she says, has added to the community's curiosity about the book. "At book signings, we have found out people know the unidentified people," she said. "People know them!"

For example, she found out that one of the unidentified women in the book was the mother of a former Smith Robertson Museum curator. (Flucker was previously a Smith Robertson curator as well.) The excitement the book has stirred in the community was evident at the Lemuria book signing where people told Savage that that the book was "a memory-lane journey" or "like going home." This feedback, Savage says, "confirmed for us we had done what we had set out to do."

For outsiders looking to learn a detailed history of the community, the book is less forthcoming. Yet, if one digs, there are still interesting insights into the psyche of the community. It is hard to engage with the visual imagery because many photographs are low-resolution headshots of prominent citizens, group shots of classes or teams, or the iconic images of civil rights leaders and events. Also, the lack of specificity in captionsfor example, how long a certain company was in business, or when a particular ceremony was heldis disappointing. Yet, where the book succeeds for the outside reader is in its analysis of why these photographs exist at all.

Savage and Flucker assert the significance of the camera as a tool that helped Jackson's African Americans preserve their history, and throughout the book, they highlight the fact that individuals were purposefully photographing themselves to document their place in history.

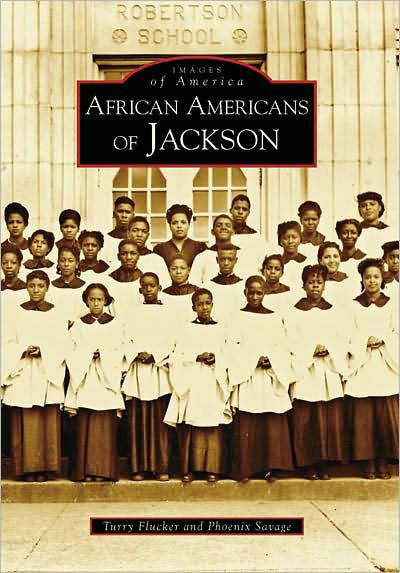

In the section on education, for example, two postcards depict classes at Smith Robertson School, one following a fire that destroyed the school in 1909 and the other following renovations to the building in 1929. The accompanying captions describe not only the significance of these scenes in Jackson history, but also the added significance that they were postcards which were, at those times, a national trend. Savage finds this noteworthy because "this very humble, struggling school did not lose sight of their place in that national craze."

In the process of compiling the book, Savage began noticing the agency involved in photographing oneself, one's business or church. "We really appreciated those real subtle elements of how someone or a group of people were placing themselves forward. Their concern was that there would be a record of their existence. We don't often think of that concept when we think of African Americans," she said. "It's important to just say, 'thank you' to the African American community of Jackson for living their lives and for choosing to leave behind images for this book.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 131173

- Comment

This is the sort of thing that belongs in a museum.

- Author

- LatashaWillis

- Date

- 2008-06-25T20:44:12-06:00