"Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.Martin Luther King, Jr.

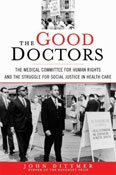

It wouldn't be fair to describe John Dittmer's "The Good Doctors: The Medical Committee for Human Rights and the Struggle for Social Justice in Health Care" (Bloomsbury Press, 2009, $30) as a story about failure, but it does reveal some harsh, Calvinist truths about what it means to stand up for social justice. Like "Local People," Dittmer's Bancroft Prize-winning history of the Civil Rights Movement, it portrays fallible human beings who didn't always get along, didn't always know what they were doing, and still managed to accomplish something. Although he's describing a small group of accomplished, extremely well-educated and compassionate peoplephysicians dedicated to desegregation, civil rights and universal health careDittmer describes a host of scenarios that today's activists may find familiar: petty grudges, poorly attended rallies, unpaid restaurant bills, naiveté and the general sense that things are not coming together as well as anyone had planned.

Dittmer describes a Medical Committee for Human Rights consisting of courageous but imperfect people who found something they believed in and then watched their organization slowly lose its influence and ultimately fall apart due to money, politics and internal drama.

However, they still accomplished amazing things and emerged on the right side of historywhile so many of their quieter and more respected colleagues in the national medical leadership, proudly above the fray at the time, maintained their credibility by becoming increasingly complicit in the deadly oppression of the poor.

Dittmer clearly does not belong to the "they don't make 'em like that anymore" school of thought. The ruthless honesty of Dittmer's biographies reveals a truth that today's activists need to hear: that nobody is really qualified to be an activist. In other words, they make 'em exactly the way they used to. Dittmer excels at describing not only the fallible humanity of our heroes, but also the unchallenged credibility of our villains.

Case in point: It is now widely known that southern affiliates of the American Medical Association often excluded black physicians prior to and during the civil-rights era, but when the MCHR was founded in 1964, even the National Medical Association, a historically black counterpart to the AMA, refused to directly confront this reality. Although the AMA finally banned segregation in 1968, it was not until 40 years later in a 2008 apology, that the AMA formally acknowledged that this segregation had ever existed. The anti-segregation position of the MCHR now seems like the only reasonable position to take, but a half-century ago, advocating this position would have marked someone as a crackpot. MCHR members had the courage to sound like crackpots, and Dittmer does a good job of conveying what they faced.

While the MCHR folded, many of the activists who comprised it continued their mission in other ways. In the final chapter, Dittmer briefly mentions how one former MCHR activist, Dr. Aaron Priestley, had the idea to convert the commercially failing Jackson Mall into a comprehensive medical facility serving the urban poor. Encountering some initial resistance, he won a $350,000 Genius Grant from the MacArthur Foundation in 1993 and began soliciting donors. Two years later, his projectthe Jackson Medical Mallopened.

His efforts reflect a natural continuation of the MCHR's commitment to universal health care, which has been broadly recognized as a basic human rights goal since its inclusion in the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The United States stands alone as the only industrialized democracy in the world to treat health care as a privilege rather than a right, making it financially inaccessible to 43 million people and subjecting 38 million Medicaid recipients to an inadequate standard of care. The disparity the MCHR attempted to address by desegregating health services in the South remains.

Although the MCHR is long gone, its work continuesmade up of the same kinds of imperfect heroes who founded the organization 45 years ago. We can become heroes, too, if we're imperfect enough to join them.