Lori Gregory-Garrott opened her front door suddenly and looked at her sleepy Fondren neighborhood with anticipation. It was just before 10 p.m. Nov. 8, Election Day. The neighborhood was quiet and dark, although her porch light was on, backlighting the Parents Against Mississippi 26 signs on the edge of her lawn. Garrott looked to the left and to the right, then ran out in the middle of her front yard. She looked side-to-side one more time, then yelled, "We just won!"

A group of women gathered in the open doorway cheered, giggled and hugged. Garrott yelled again, louder, "We just won!" She looked around her neighborhood, then cocked her head back and looked straight up at the night sky and screamed it one more time to the heavens: "We just won!"

Inside the house, about 20 women shouted, hugged and cried when CNN declared the failure of the Personhood Initiative, a measure that proposed amending the state constitution to define a person at the moment of fertilization. "This is how we do it!" someone yelled from the hallway.

"I didn't think it would happen," Garrott said, sinking into a chair in her living room. After her elation and shouting, she began to cry. "In one second, I realized the coup we just did." Other women hugged her.

More sifted in from the kitchen, one with a 6-week-old baby girl. One of the women opened up a laptop, got on YouTube and played a music video, "All I Do Is Win." Someone else found the On Demand videos on the TV, and then they danced to "Baby Got Back!"

Michelle Colon, an activist who started Hell No! on 26 and 27, showed up at the house party, hugging everyone. While she was elated that Initiative 26 failed, she wasn't happy that Initiative 27 requiring voter identification at the polls passed.

"It's a poll tax," she told some of the women on the couch.

Colon said she is worried that white liberals didn't care enough about voter ID. She's heard many people say: "What's the big deal? So you have to show your ID?" She explained this to the women on the couch between dance sets. The women talked about the energy they had now to tackle more social issues.

"Look at us," Colon said. "Christians, whites, blacks, Rankin County housewives—we did it! There will not be a theocracy."

Baby Shower PAC

Stacey Spiehler was the Rankin County housewife on the couch. She said she doesn't live in poverty, and that her life insulates her from a lot of harsh realities.

"I can't imagine what it's like for a woman in poverty to be pregnant. That's kind of a life ruiner," she said.

Spiehler has a way of measuring time by which television set she owned. She remembers it was well over a year ago that she saw the first Personhood commercials because it was on her older, smaller TV. She went to the website and looked at the language of the initiative and was shocked it had no provisions for the life of the mother.

"It just set off alarm bells," Spiehler said. Her ectopic pregnancy, a painful memory, could have ended differently in a Personhood world. She called the number on the website, and a man answered the phone.

"A man," she repeated and paused.

She told him her concern and asked if this was true: Was there no exception for the life of the mother?

"We're just trying to get it on the ballot," the man told her.

Those words stuck with her. It bothered her, it even hurt her, but she didn't do anything else for almost a year. When she learned in early September that Personhood would definitely be on the ballot, she spoke up.

"That's when I started looking around for ways to fight it. I was so hopeless," she said.

She saw no one standing against it. She heard no one saying it was wrong. She thought Mississippians would pass the initiative without hearing all the facts.

Spiehler and her friend Atlee Breland went to a baby shower, and it's all they could talk about. They met another woman at the shower, Merrill Nordstrom. Breland was starting a website and a political action committee for Parents Against Mississippi 26. Nordstrom had an idea about making videos of women's personal stories to illustrate why they opposed Initiative 26. The three became the officers of the new PAC and flew into action.

The political whirlwind of the two months before the election took a huge investment of time for all three. The financial reports PAMS26 filed with the Mississippi Secretary of State's office show the PAC only spent $247. They took time away from work and other duties to research, educate, circulate and keep a constant conversation flowing.

"I'm angry. I'm angry I had to spend time on this," Spiehler said.

"It took me away from time with my son, my family. I neglected my house."

Almost 60 percent of Mississippians voted no on Initiative 26. The day before the election, Lt. Gov. Phil Bryant, who is the governor-elect and the co-chairman of Personhood Mississippi, compared opposing Initiative 26 to supporting the genocide of Jews in Nazi Germany. He said opponents to Personhood wanted the right to end life. If the measure failed, Bryant said, "Satan wins."

No Disney Princesses

As soon as Mississippi Supreme Court justices decided Sept. 8, 2011, that they wouldn't stop the Personhood Initiative from appearing on the November ballot, women in the state started talking a little bit louder. Michelle Colon heard some women say they would leave the state if voters decided a fertilized egg was a legal person. She shared their anger and repulsion at the implications, but she didn't think they got the bigger picture for Mississippi.

"Not everyone has that option," Colon said. "Not everyone can leave the state."

Colon probably could. She's a professional fundraiser for a nonprofit and is well educated and well traveled. She grew up in Chicago and Miami. But she worries about poor girls and women in the state who might be stuck in bad situations for life.

"Somebody needed to stay and fight," she said.

Irritated and surprised by the lack of organized opposition to the Personhood push, Colon started a Facebook page called Hell No! on 26 and 27. Colon saw a connection between the two initiatives—the Personhood Initiative 26 and the voter-identification initiative. Both initiatives would hurt African American women like her, she said.

Colon felt she had no choice but to start Hell No! The first week or so after the court decided Personhood was fair game, Colon noticed an odd silence from many organizations that usually speak up for women's rights, including reproductive rights. Planned Parenthood, the National Organization for Women and The Women's Fund were quiet on the issue even as late as mid-September—less than two months before Election Day. State and local chapters were almost conspicuous by their absence. Some were deciding strategy and put immediate action on hold in anticipation of funding. Colon wasn't waiting any longer.

"No one was going to rescue us," she said. "We rescued ourselves."

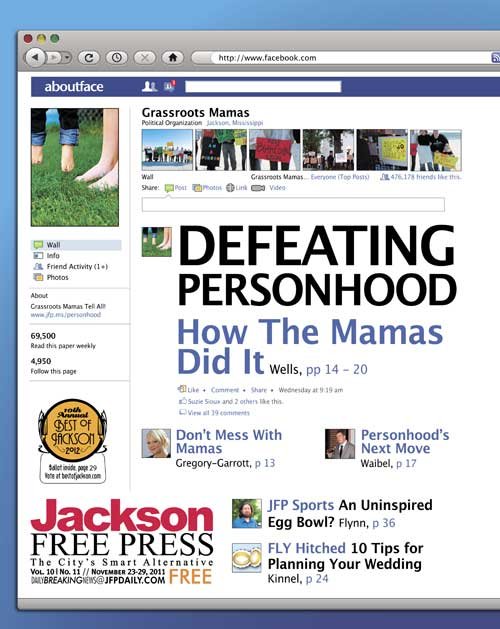

Some of the women and men who met and worked to defeat Initiative 26 intend to keep fighting future Personhood efforts. Garrott, a social worker and an early member of Parents Against Mississippi 26, is working with other professionals to compile and send all the research from this autumn to other states battling Personhood threats such as Florida and Ohio. She wrote a column against Personhood for the JFP in March 2011 and for this issue (click to read her latest, "Don't Mess With Mamas").

Garrott, 35, had followed the Personhood movement in Mississippi for some time before the Sept. 8 court decision.

After the decision, she found others who actively sought to defeat the measure. Then she flew into action.

"Two months, that's all we did," Garrott said. "I wish halfway through I realized how much fun we were having." Instead, she spent much of September and October anxious and scared, but driven.

This summer, she attended Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann's public hearings on the initiatives. "I wasn't really engaged," she said. While Garrott was watching developments with the Personhood push, she expected the state Supreme Court to keep the measure off the November ballot. "What were the odds?" she said.

Garrott found it interesting to hear people speak against the Personhood Initiative this summer. The hearings she attended were split about 50-50; if 14 people spoke, seven of them were opposed and seven were in favor. It was an interesting observation she tucked away. One person opposing the initiative who caught her attention was an older, white man who didn't want his daughters facing the health consequences of a forced pregnancy, she said.

Political Inaction?

Four groups opposing Initiative 26 took the formal step to create political action committees by filing papers with the Mississippi Secretary of State this autumn. The law requires political groups raising money to file reports on contributions and on expenditures. The four that filed initial paperwork include the following.

• Mississippi Doctors Against 26, with four Mississippi physicians listed as officers: Dr. Randall Hines, Dr. Wayne Slocum,

Dr. E. Charles Gnam and Dr. D. Paul Seago.

• Students Voting No on 26, with Diane Cutri, a representative of the Feminist Majority Foundation in Arlington, Va., as the sole contact.

• Parents Against Mississippi 26, with three Mississippi women listed as the officers: E. Atlee Breland, Merrill K. Nordstrom and Stacey Spiehler.

• Mississippians for Healthy Families, with two Mississippians listed as officers: Nsombi Lambright, ACLU of Mississippi executive director, and Kay Scott, CEO of Planned Parenthood Southeast Inc. This PAC filed its initial paperwork with the Secretary of State's office Aug. 23, a couple of weeks ahead of the state Supreme Court's decision. Funders included several regional Planned Parenthood affiliates, much of it listed as "in kind" contributions.

The ACLU Foundation and ACLU of Mississippi also gave "in kind" contributions.

Parents Against Mississippi 26 and Mississippians for Healthy Families filed receipt and expenditure reports with the state. Mississippians for Healthy Families raised more than $1.3 million as of Nov. 10 and spent more than $850,000. Parents Against Mississippi 26 reported its total contributions at $247.84 with only $47.84 in expenses.

Yes on 26 raised more than $1 million ($296,286 of it from Colorado-based Personhood USA) by Nov. 10 and spent about $214,000. Personhood Mississippi, Les

Riley's group, raised $34,247.75 by Nov. 10 and spent $32,089.66.

Backers of Yes on 26 said Mississippians for Healthy Families was a front for the ACLU and Planned Parenthood.

Stan Flint, a strategist who consulted for Mississippians for Healthy Families on its campaign, said it was actually hundreds of groups and individual Mississippians who came together to form a coalition. He mentioned that he remembers the first time he met Felicia Brown Williams, regional director of public policy at Planned Parenthood Southeast. He was a friend of her father, and he visited their home near Hattiesburg often.

"She was 2 weeks old, and I held her on my knee," Flint said.

He stresses the role of long-time Mississippi residents who fought Personhood. Flint, managing partner of Southern Strategy Group, said in 40 years of lobbying and professional political advising, he has never seen a campaign come together so seamlessly.

"It took two or three weeks to sort of get a plan," Flint said. "It takes three months normally. This was very different. There was a lot of frustration. A lot of people took a DIY approach: do it yourself."

One example he gives is the Lafayette County Women for Progress, based in Oxford. He had high praise for the DIY-ers.

A plan wasn't in place before September for several reasons. One was Personhood Mississippi's creation of a difficult and hostile environment. "Nobody could mobilize against a national campaign," Flint said. "People in the state teamed up. We put together a close-to-perfect campaign. That usually takes about a year."

So why didn't that coalition start a campaign a year ago to defeat Initiative 26? It comes down to funding and support from outside the state, Flint said. Without money, opponents couldn't wage an effective campaign. "The only way that trigger gets pulled is by a specific thing," he said. In this case, that pulled trigger was the Sept. 8 Supreme Court ruling that refused to block Personhood from the ballot.

"I know a lot about difficult campaigns. We didn't know if we could mobilize the resources," he said.

Mississippi For Healthy Families and other existing organized groups were silent for a couple of weeks following the court's decision on purpose, he said. The professional, organized players wanted to carefully frame the issue. That's why they wouldn't allow representatives to talk to media right away. Planned Parenthood representatives did not return calls from the Jackson Free Press for at least a week following the Supreme Court ruling.

"We had to control words to control the debate to control the election," Flint said.

The main tactic of Yes on 26, he said, was to alienate people with emotionally charged language: "They were hollering at the boogie man behind the tree. They wanted to take advantage of our faith. People from Mississippi have intuition. They smelled a rat."

He pointed out the religious leaders who opposed Initiative 26, including the Rev. Duncan M. Gray III, bishop of the Episcopal Church in Mississippi. Mississippi Doctors Against 26 and the other medical groups that spoke out in opposition made a huge impact.

Flint also gave props to the social-media surge and grassroots groups. He says they kept momentum going and got things ready for when Mississippians for Healthy Families was ready to tell the world its plan. He admits he's not that familiar with social media, but recognizes it was an almost invisible force for would-be activists with a desire to stop the measure.

Mississippi Autumn

Activists may not have thought about the Arab Spring when they began venting on Facebook, but the organic growth of a movement beyond sanctioned spokesmen and message "control" had its similarities, including a core group of friends and family.

When the state Supreme Court didn't move to block the initiative appearing on the ballot, Garrott was surprised and decided to catapult into action. Others joined her—without the level of concern about framing that Flint spoke about.

"We learned a lot in a short amount of time," Garrott said. "We really didn't think they would allow it on the ballot. We said, ‘What the hell are we going to do?'"

Like Colon, Garrott saw no leadership against Personhood in mid-September from the organized groups. "There was a lack of organization. There were a lot of us talking about it," she said.

Groups started to form and appear, some informal and some highly organized. One of the more organized was Mississippians For Healthy Families, a group the Yes on 26 crowd attacked almost immediately for being a puppet of the ACLU and Planned Parenthood.

"The meme was that Mississippians For Healthy Families was Planned Parenthood," Garrott said. She sensed trouble. "We don't have a separate voice," she told friends. "There's no way we can win if we don't."

Whether the quiet stance of Planned Parenthood and other organizations was on purpose or not, Garrott sensed a need for mothers like her to speak and to scream.

"ACLU and Planned Parenthood are not loved here," she said. "There's got to be a voice of Mississippi, and this was a battle going on between outside entities."

"If you have that voice and aren't afraid to say it, you need to say it," her family told her. So she did, and so did many of her like-minded friends.

"We felt lucky we were in a position where we could be loud," she said. "I have a wanted child, I own my own home, I have a wonderful husband, and I pay taxes."

Garrott grew up in an Italian Catholic family in Greenville. She lives in Fondren now. In some parts of the state, she said, some women don't feel as if they can be loud. She attributes that to fundamentalist Christians like the ones behind the American Family Association and Yes on 26.

"They really have their hooks into people," she said.

Garrott and her friends got on Twitter and Facebook to vent and then started organizing. "It was organic," she said.

A core group naturally and easily seemed to take on regions and duties. In Starkville, student Shannon Denney dug her heels in. Myles Ray, an activist on the Coast, was in Biloxi. Cristen Hemmins, a rape victim at age 20 who this year—at age 40—sued the state to keep the Personhood Initiative off the ballot, lives in the Tupelo area, the stomping ground of the American Family Association.

Stacey Spiehler, a stay-at-home mom who had suffered an ectopic pregnancy, reached out to conservatives and spoke to the media. Atlee Breland, a mother of three thanks to in-vitro therapy, started a political action committee, Parents Against Mississippi 26, and talked to national media. Michelle Colon went to the universities and colleges, especially the ones in the Jackson metro area, to motivate students and found plenty who already were up in arms.

Many other women and men played roles, especially in communities with hospitals and universities, Garrott said. She saw a direct correlation between communities with more higher education degrees and precincts that defeated Initiative 26.

One of the biggest lessons she learned from fighting Initiative 26 was how to make a non-emotional argument, Garrott said. She and her fellow 26 opponents learned much in a short time from doctors and lawyers, as if they were cramming for the ultimate final.

"We all got a little law," she said.

Fighting ‘Slacktivism'

Myles Ray now has the reputation of being the grassroots guy on the Coast who got things going on Facebook with his page, Vote No on Mississippi Amendment 26.

Ray started the page in early summer 2011, months before the Sept. 8 ruling. As other frustrated Mississippians started using social media to vent in September, many of them found Ray's page and began doing more than just venting. "We need someone to show up at this press conference." "Can someone go to the rally in Oxford?" Ray's Facebook page became the de-facto hub of activity for grassroots opposition to Initiative 26.

Ray, 33, grew up in Arkansas but has spent most of his adult life on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. He says he was a minor community activist who helped people register to vote, but then Hurricane Katrina came. He decided to get out of politics, he said, after he saw the government response to the general devastation of lives on the Coast. Then, he got wind of the Personhood Initiative and shook off his political funk.

"My family was pro-choice; my grandparents were pro-choice," he said. "This has been a healing experience. I started meeting with people in Biloxi. It got me off the computer. ‘Slacktivism' only goes so far. Social networking is great, but it can't be the end all. Not everyone has a computer."

Ray organized rallies on the Coast, planned meetings with other activists and talked to people about the implications of a zygote having the same rights as a person. Now that voters have defeated 26, Ray wants to keep the political momentum of this new group of friends going strong. He still wants to communicate with the world his perception of just how extremist the American Family Association is. A lot of polite Mississippians have been content to let the AFA have its say, no matter what.

"We have been complicit in our silence," Ray said.

Besides Ray's Vote No page and Colon's Hell No!, a half dozen other Facebook pages emerged full of Mississippi voices—some outraged, some subdued but shocked at a possible illegal future of birth control.

At an Oct. 13 protest, Colon traveled to Starkville from Jackson to support the students. When local media tried to interview Colon, she pointed at a student from West Point, Shannon Denney. "You should talk to her," Colon said.

Denney, 21, had just started her senior year at Mississippi State University. Even though she plans to graduate in May with a degree in political science, she did not intend to get involved in any campaigns. She was thinking more about which law school to apply to. Denney expected to spend time outside class studying and hanging out with friends. Then she saw a friend's post on Facebook about the Personhood Initiative. It was kind of news to her and to many MSU students.

"What's going on?" she asked everyone around her.

"Nobody really had a clue about this," Denney told the Jackson Free Press this month. "That was our biggest challenge—no one knew about it." She decided that had to change.

"OK, we're not taking this," Denney told her friends. She organized a small group to get the word out. "Just show them why they should care," she said.

Denney started researching the topic and its implications, finding articles and then urging people to pay attention. She would find a news story with facts and figures. "You need to read this," she told friends and acquaintances. She didn't let up.

"I had never been involved in anything like this before," Denney said.

She started a Facebook page, Mississippi State Women and Men Against 26. While she got the attention of students, she also had MSU alumni and Starkville residents "liking" the page. Her group handed out flyers, organized rallies and talked to the media.

"In political science, you see how voting goes in certain states," Denney said. "One person can make a difference. We always heard that when we were little. We saw a real need for education and motivation here. So, yes, one person can make a big difference."

She's waiting to see how she might continue to fight Personhood in other states or how it might show up in the Legislature. "This isn't over. People need to realize that," Denney said. "It's not a big organization that fought this. We can't forget how this started."

Election Night: Victory

Those who fought the measure will likely not soon forget the empowerment of defeating what some national experts had written off as a foregone conclusion.

Activists who worked on several grassroots campaigns nervously watched the percentages after the polls closed Nov. 8. Some met at Ole Tavern on George Street to wait for the returns.

"It's been a long couple of months," Colon said at the Ole Tavern gathering. She saw two months of hard grassroots activism paying off. It reassured her in the final days that the initiative would fail. "A lot was done with little money," Colon said.

Shelley Abrams, executive director of the Jackson Women's Health Organization, wore a T-shirt that read "Get Out of My Vagina!" at the Ole Tavern gathering. About a dozen activists opposing Initiative 26 waited for results, including people from Mississippi ACLU and Mississippi Center for Justice. Abrams represented the group Wake Up, Mississippi.

Earlier in the day, Abrams stood on the side of the highway in Clinton dressed as an egg with others who opposed the initiative. She also donated money for the "Eggs Are Not People" billboards opponents put up.

"The world is watching us," Abrams said after a television news crew from Al Jazeera showed up. A reporter from Reuters interviewed her later in the evening.

On a somber note, Abrams said if the initiative failed, a real danger lurked for doctors who work at her clinic, the only abortion facility in Mississippi now, which is in Fondren. She didn't want to create fear or drama, she said, but it is a reality she has to consider.

Whitney Barkley, who works for Mississippi Center for Justice, suggested if the Personhood Initiative passed, then all women should leave the state. "It's like the Day Without Immigrants," she said. "It will be the Day Without Women."

"I hope Mississippi shows the rest of the country we're not as backward as they think we are," Lilly Lavner said as the results started to pour in.

Mississippians for Healthy Families and Parents Against 26 had a political watch party at Walker's Drive-In in Fondren. At 9:30 p.m., activists paced the sidewalks, all of them on cell phones. The major news outlets were about to announce the defeat of the initiative. Atlee Breland, founder of Parents Against Mississippi 26, stood still on the sidewalk, sharply focused on every new tidbit.

A few blocks away, Garrott shrieked at the stars in joy.

But the outspoken supporters weren't the only ones who defeated Initiative 26. Conservative women, perhaps quietly, were key players—and helped take 26 down with 58 percent of the vote.

Voters elected two Republican women to state offices: Lynn Fitch, state treasurer, and Cyndi Hyde-Smith, agricultural commissioner. Both publicly supported Initiative 26, although their jobs have nothing to do with reproductive rights. Connie Moran, the Democratic mayor of Ocean Springs who ran against Fitch, was the only candidate for state office who opposed the measure.

Still, voters also elected Phil Bryant governor, even some of whom must have fallen into the "Satanic" category by his standard. Some people who voted against Initiative 26 must have also voted for Bryant, Fitch and Hyde-Smith. Politico.com said the defeat of 26 represented a break in Mississippi conservative group think. The New York Times theorized it came down to the tricky health issues connected to fertilized eggs.

Several national media and state reporters sought expert observations of political scientist Marty Wiseman of the Stennis Institute of Government at Mississippi State University. He told The Christian Science Monitor and The Los Angeles Times, among other news organizations, that conservative women who are anti-choice listened to the medical professionals who spoke out early against the unintended consequences of giving a zygote the same rights as an adult woman.

With Mississippi's conservative voter base, the defeat of Personhood seems more likely in other states if activists can replicate what Stan Flint calls the sophisticated and complex arguments made here. Sometimes it wasn't even an argument. A few conservative women posted pictures of a cancerous tumor on Facebook with the simple notation, "This is a fertilized egg."

Occupied State of Mind

The newborn activists expect a Personhood fight in the Legislature come January. Many of them swear they are chomping at the bit to tweet and protest and watch Mississippi legislators like hawks.

Garrott is demanding that Gov.-elect Bryant, co-chairman of Personhood Mississippi, apologize for calling 58 percent of Mississippians "Satan" for defeating his pet initiative. She hasn't heard or seen the apology, yet, but she continues to respectfully demand it. Someone else has a started a Facebook page called Phil Bryant You Owe Mississippi an Apology.

Personhood USA organizers are already working to get the measure on ballots in Florida and Ohio. The talk is that they are already collecting signatures again in Mississippi to try one more time.

Now that 26 is defeated, Spiehler is wondering how she might make a difference. She's thinking about how to help start effective sex education for teens and children and how to help young mothers who chose to have babies they can't afford. That seems to be a missing link she sees in the anti-abortion movement. She is still upset with the Personhood movement and its pushers.

"I wish they had everything figured out from the beginning instead of deny, deny, deny," she said. The spiritual bullying of the Yes on 26 crowd was exhausting for her as well. "They say, ‘You're not a Christian if you are X.' I would urge this: Let's not do that again."

Michele Colon is more focused on voter identification, a measure that passed Nov. 8. She wants to make sure everyone who is eligible to vote is allowed to vote. If that means that everyone needs a government-issued ID card, she's going to get the word out. She sees the voter ID supporters who gripe about fraud as insincere. "Two days after you're dead, the state stops your checks," she said.

"If they are worried about voter fraud, they can take care of dead people on the rolls. Hire someone to do it."

The activism that Personhood awoke could be the beginning of better things for all Mississippians. Because white, privileged women spoke up, people noticed and thought, "Oh, this could happen to me," Colon says. If it were just about poor, black pregnant girls in the Delta, Colon thinks people would have looked away. The national media wouldn't have swept in during the last week before the election.

Colon quotes a line from "V for Vendetta," the 2006 movie: "People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people."

The Personhood fight is not over for her, either. Colon was struck when she went to the Delta this fall and came across so many women that didn't know about the initiative or what it meant. A well-off, educated woman could travel out of state for an abortion, she said, or her health insurance might allow her progressive-minded doctor could to perform D&C (dilation and curettage, a gynecologic treatment for several uterine conditions). But poor, uneducated girls and women in the Delta don't have those options, she said. They lack the grassroots network and the instant information to make their life better. Colon worries about them.

"Not everyone is on a computer."

Read the JFP's full Personhood archive.

Related Links

Personhood's Next Move