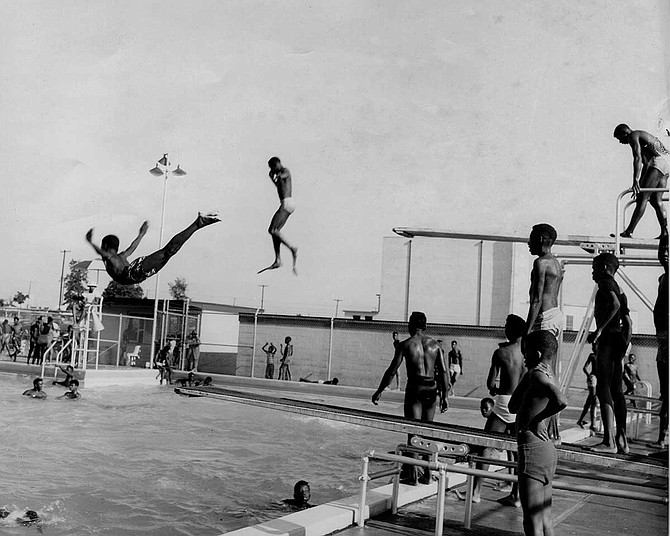

In the 1960s, black and white citizens of Jackson had to swim in segregated pools. Photo by Roy Hargrove/MDAH

JACKSON — By 1961 in Jackson, black and white citizens could not legally drink from the same water fountains—nor could they swim together in the capital city's taxpayer-funded swimming pools. That year, a group of black Jacksonians began demanding that pools here be integrated.

As a result, Mayor Allen C. Thompson and city officials, all white then, closed four public pools in 1963 rather than integrating them, much as white officials across the South had threatened to close rather than integrate public schools after the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision. The City sold the fifth to the YMCA, which continued to operate it as a whites-only pool. The City of Jackson argued, after closing the pools, that integrated ones could not operate safely nor economically.

Unlike Brown, however, the U.S. Supreme Court did not intervene and force public pools to re-open after officials closed them. Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy explained the Palmer v. Thompson case, which upheld local pool closings, at the "History Is Lunch" speaker series at the Two Mississippi Museums on Wednesday, March 15. The U.S. Supreme Court, he explained, ruled that closing the pools to everyone did not deny equal protection of the laws under the 14th Amendment. The court also ruled that the case did not violate the 13th Amendment by creating a "badge or incident" of slavery, as the plaintiffs had originally argued.

"Closing the pools was just segregation by other means," Kennedy said.

The precedent allowing the City of Jackson to close the pools rather than integrating them still stands.

'We Are Not Going to Have Any Intermingling'

The residents challenging the racial segregation of recreational facilities had won a declaratory judgment from federal Judge Sidney Carr Mize, who determined that it is unconstitutional to segregate publicly owned recreational facilities. Mize was a U.S. District Judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi.

After the ruling, Jackson officials began to desegregate most recreational facilities, with the exception of public swimming pools. Officials allowed the sales of public pools to private companies, who could then privatize them. Jackson had five public pools then—four for whites and one for blacks.

"We will do alright this year at the swimming pools, but if these agitators keep up their pressure, we would have five colored pools because we are not going to have any intermingling," Thompson told the Jackson Daily News, then an openly racist newspaper.

Thompson was also known for the "Thompson tank," which the City of Jackson used to disperse and intimidate civil-rights protesters.

African American activists in Jackson pushed the matter, resulting in Thompson closing the swimming pools. Hazel Palmer—a mother, maid and Jacksonian—filed a lawsuit against the mayor in 1965. She dove into civil-rights activism because of her son, Alpha Zara Palmer, a freedom rider. Police arrested him, along with five other freedom riders, at the Illinois Central Railroad terminal in Jackson on July 6, 1961. She filed the lawsuit to show solidarity with her son, she said then.

'A Notorious Segregationist Judge'

Every court ruled in favor of the City of Jackson's decision to close the pools, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The mayor set forth two justifications for closing the pools: one for public safety and two for the expense. Palmer and other black activists argued that closing the pools was just another way to keep Jim Crow segregation in place.

U.S. District Court Judge William Harold Cox made the first formal ruling in favor of Thompson in the case.

"A notorious segregationist judge," Kennedy called him, adding, "A number of the cases Harold Cox adjudicated are discussed in this museum."

The judge ruled in favor of city authorities, accepting Thompson's justifications. "Cox made factual findings, affirming, yes, that's why city authorities closed the pools," Kennedy said.

After the City of Jackson won in U.S. District Court, Palmer and other black activists then appealed to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, "which was known to civil-rights folks as a good place to go," Kennedy said.

The 5th Circuit affirmed Cox's ruling, however. Palmer and company then requested an en banc hearing—a session in which a case is heard before all the judges of a court as opposed to a selected panel.

After the hearing, the full court too reaffirmed the ruling. Palmer then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which reached a 5-4 decision in favor of the City of Jackson. Justice Hugo Black's opinion affirmed the district court, the court of appeals and the 5th Circuit, holding that, no, it was not a violation of the U.S. Constitution for city authorities to close all of the swimming pools to keep from integrating them.

This case was never overturned. To date, the City of Jackson still has five public pools, now desegregated since 1975, open only during the summer, its website says.

Intern Reporter Natosha Pengarthit covers the City of Jackson and the Jackson City Council. Email her comments and story tips to [email protected].

More stories by this author

- City to Launch Pre-K Pilot Program With Grant From the Kellogg Foundation

- Second Woman to Lead Tougaloo College After First Retires After 17 Years

- 'Go Clean JXN' Launches Saturday With Residents Helping Pick Up Trash Citywide

- Water Customers Still Getting No Bills as City Scrambles for Payments

- After Death in Madison Jail, Family Files Lawsuit Against County