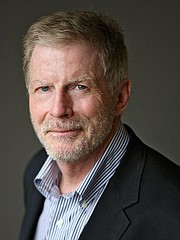

U.S. Senate candidate David Baria took what many would say was a daring political stand on the Mississippi flag during his campaign. Photo courtesy Baria Campaign Photo by Baria Campaign

JACKSON — It's hard to know whether it cost him votes, but there was a moment during Mississippi Rep. David Baria's unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate that caused a surprised buzz around a state where the conventional wisdom is that criticizing odes to the Confederacy is a political death knell.

After he won the Democratic primary, Baria released a campaign video where, at one point, he stands confidently in front of the Mississippi state flag, points his thumb backward at it, scrunches up his face and says "really!?"

Baria's take on the absurdity of the continued use of the most iconic Confederate battle emblem in the state flag is one that many Mississippians, of all races and even political parties, feel on a regular basis—a flag saluting a war to preserve slavery; really!?—but it is not a position that politicians of any party have felt very comfortable expressing here over the years.

Mississippi Flag: A Symbol of Hate or Reconciliation?

The Mississippi Sons of Confederate Veterans are fighting hard to keep the state flag to honor the Confederacy. Others are fighting back.

For many white Mississippians, Confederate iconography was part of their upbringing, used to frame the Civil War as a "lost" and glorious cause—a way to justify a very bad war fought by a state where 49 percent of white families owned slaves as that war began, as well as villainize the Reconstruction era that followed.

And it is, after all, a state where it is a legitimate concern whether U.S. Sen Cindy Hyde-Smith made her "public hanging" comment purposefully in order to draw the bigoted voting bloc, or would not acknowledge the pain of her words later for the same reason. Either way, that kind of racist dog-whistle is common, with the politician almost always immediately calling any race associations "ridiculous," as she did Sunday.

Still, many white Mississippians, even powerful politicians and businessmen, have long wanted the flag to change, but treat it like the third rail of state politics—they will surely be electrocuted if they dare say they want to replace it for any other reason other than that it makes outsiders like and invest in Mississippians less. The last thing they've been willing do, even back in the failed 2001 referendum to change the flag, is say the s-word in relation to it. That is, don't talk about slavery; just say bad people such as the Ku Klux Klan co-opted the flag well after the Civil War. Alas, that cautious flag-change strategy has failed dramatically to date as the symbol still flies overheard.

Does that mean it's time to try a more straightforward approach, a more honest one, such as what Baria attempted? Some native Mississippi Republicans believe it is.

'Race Is Probably the Key'

Republican political strategist and writer Stuart Stevens, who grew up in Jackson, was named for a great-uncle named for Confederate Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. He is also a persistent Donald Trump critic, including over race division.

Stevens is the son of an FBI agent who later founded Butler, Snow, O’Marra, Stevens and Canada law firm—now just called Butler Snow. He badly wants the state flag changed, even as Mississippi leaders drag their feet to avoid political backlash.

Now based in Washington, D.C., Stevens, 65, says his family was "cognizant on race," with a civil-rights attorney uncle and a grandmother who co-founded the Southern Women's Anti-Lynching Society.

Still, until recently, he didn't think of the Confederate flag as having more significance than the love for Ole Miss football he shared with his father, Phineas Stevens, back when the cheerleaders waved rebel flags on the field.

"It was not really on my radar," Stevens admits now. He changed his mind during discussions about Confederate statues in recent years. "This idea that somehow history demands that we put up statues of (Confederate Gen.) Robert E. Lee I think is insane. I am completely against this revisionist history of the 'lost cause,' which I was very much taught to believe in school."

Stevens, a Murrah High School graduate, criticizes what he frames as a timid 2001 campaign to change the "bad for business" state flag because outsiders did not like it.

"I don't think we ought to change the flag just because we could get a car plant," he says. "... For 40 percent of the state, it reminds them of when white people owned black people. Why aren't you trying to protect them from that pain?"

When it comes to race, self-interrogation is needed across the country, Stevens believes, including far from the heart of Dixie. "They haven't done this reckoning in Queens," he says of the New York City borough. "Parts of Queens are horribly racist.

"But arguably there is a greater responsibility for a state like Mississippi to address this. Race is probably the key to all American life—certainly in Mississippi."

'Why Should We Change It'

After 17-year-old honor student Raynard Johnson was found hanging by a belt from a pecan tree in his yard in June 2000, his death ripped like a tornado through rural Marion County in south central Mississippi, leaving raw dissension in its path. Authorities ruled Johnson's death a suicide, but his parents believed the well-adjusted black teenager was lynched, maybe because he sometimes dated white girls. (The U.S. Department of Justice later closed an investigation into Johnson's death.)

TJ Harvey, now 35, had shared a third-grade class with Johnson in a conservative area not exactly known for enlightened race dialogue.

"It drove division in ways people didn't expect," Harvey, who is white, says of the hanging on the road where his grandparents lived.

Raised as a conservative Christian, Harvey never thought much about Confederate emblems. Still a "Republican-libertarian" today, Harvey believes in small government and states' rights to be free from federal oversight.

Ten months after Johnson's death, the 2001 referendum to replace the Mississippi flag—based largely around the change being good for business rather than the flag's roots in slavery and oppression—drew then-18-year-old Harvey to the polls for the first time. Like many, he voted to keep the old banner because he despised the dominant campaign message that the existing flag offended people beyond state lines.

"I had created an opinion that anyone from the outside was wrong," he says. "This is ours, so why should we change it?"

After studying for a business degree at Mississippi State University and extensive travel, Harvey had a change of heart. He now prefers a popular replacement option designed by artist Laurin Stennis, the granddaughter of now-deceased U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis, a long-time segregationist Democrat who became somewhat more tolerant on race issues late in life.

But Harvey only shifted on the flag about a year ago. Several years back, he was with a reporter friend at a pub in Jackson, where he now lives, and admitted to voting to keep the Mississippi flag.

"Would you vote for it again?" his friend asked Harvey.

"Yeah, probably," he responded.

"I thought she was going to lose her mind," he says, smiling. He started asking friends, especially African Americans, to talk to him about it—dialogue he now believes is vital to bridging such a divide, even between conservatives and liberals.

"I think we'd find more common ground if we educated ourselves," he adds.

Harvey advises that people start small with simple conversations about what the flag really stands for and how it hurts people. "You don't have to wave a banner or post on social media," he says.

Read more: jacksonfreepress.com/slavery.

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19