Sen. Angela Hill, R-Picayune, adamantly opposed a measure that would restore the voting rights of a man convicted of murder in 1990. Photo by Stephen Wilson.

JACKSON — Stanley Barnes of Claiborne County was convicted of murder in 1990 and received a life sentence, but was paroled in 2000. He is still on unsupervised parole. Sen. Albert Butler, D-Port Gibson, introduced a bill this session to restore Barnes' voting rights.

Butler told the Senate that Barnes had worked on a farm and lost one of his legs in a tractor accident, which could have contributed to his criminal behavior, after he was bullied for several years. Butler said he now attends church with Barnes, who has made a "complete change in his life."

Barnes drives the bus for his church's Sunday School ministry, Butler added.

One day before lawmakers left Jackson on March 28, the Senate debated voting rights for Barnes, previewing what could become points of contention in future changes to the state's disenfranchisement laws.

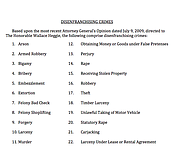

In Mississippi, someone loses his or her right to vote depending on if the specific crime is on a list of disenfranchising crimes listed in the Mississippi Constitution of 1890. The list was a way to disenfranchise African Americans from voting, a 2017 Brennan Center report found.

The Legislature has never revisited the list of 22 disenfranchising crimes, despite its racist origins, and as a result, some inmates serving time in the State's custody never lose their right to vote, while others are barred from voting for life. One provision of Mississippi's constitution allows those disenfranchised to petition the Legislature with suffrage bills, which require two-thirds of both the House and the Senate to approve before having voting rights restored.

Arbitrary Guidelines

Not all senators believe that someone who committed a crime of violence should have their voting rights restored.

"I'm shocked that I see a bill like this before the Senate, before the body," Sen. Angela Hill, R-Picayune, said. "(For) somebody who committed murder and is still on probation to have suffrage rights returned."

Hill moved to kill the bill, but Sen. Hob Bryan, D-Amory, pushed back.

"I'm shocked that there's still a provision in our state constitution that precludes people from voting forever," he said. "... It's my opinion that after someone who has been convicted of a crime has served his or her time in jail, that we should at that point make it as easy as we can for these individuals to once again—to use a trite phrase—become productive members of society."

Republican senators expressed concerns about restoring suffrage to someone who was still on unsupervised parole, but Mississippi law does not have any guidelines for lawmakers about who gets suffrage and who does not, which is why the process is so arbitrary.

"There's just something that when you commit a crime such as murder ... taking a human life supersedes almost anything else, and this is not something that I think someone ought to be able to get their voting rights for," Hill told the Senate.

Her motion to kill the bill failed, but the bill to restore Barnes' suffrage also failed to pass the Senate because it needed a two-thirds vote to pass.

Race Disparities

Suffrage requests often do not fare well in the Legislature. Rep. Andy Gipson, R-Braxton, who chaired the Judiciary B Committee in the House before recently becoming agriculture commissioner, outlined unofficial rules that his committee has used for several years, he said, to evaluate the proposed legislation.

"No violent crimes, no crimes of violence, no public officials who embezzle money and lose their office, nobody who got a conviction and then got back into trouble with the law again or violated the terms of their parole or probation and generally, we like to see a period of about five years or more before they seek this request, so they've demonstrated that they are a law-abiding citizen," Gipson said in the last weeks of the session.

These arbitrary rules would have rendered Barnes' request for suffrage moot even if it had passed the Senate. Gipson's committee killed three of the eight House suffrage bills introduced in 2018. Overall, only 50 percent of suffrage bills passed the Legislature this year. They are due from Gov. Phil Bryant next week but become law without his signature. He has never signed a suffrage bill.

Ironically, as lawmakers debated restoring voting rights to a handful of individuals, others who are disenfranchised from voting stood across from the Capitol and announced a class-action lawsuit against Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann.

The lawsuit claims that Mississippi's list of disenfranchising crimes is unconstitutional, as well as the suffrage process. The Sentencing Project, One Voice and the NAACP of Mississippi released a report earlier this legislative session that estimates that more than 218,000 people in Mississippi are disenfranchised due to the list, and African Americans are still disproportionately affected.

Nearly 16 percent of the black electorate in the state of Mississippi are disenfranchised, the report found, using 2016 numbers.

Bryan said his Judiciary B Committee plans to study disenfranchisement and the suffrage process this summer, and its work could be crucial as the state will have to deploy attorneys and taxpayer dollars to defend Hosemann in the litigation brought by the Southern Poverty Law Center. A measure to create a study committee that would look at disenfranchisement has passed the House several years in a row, but died again this year in the Senate.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @arielle_amara.