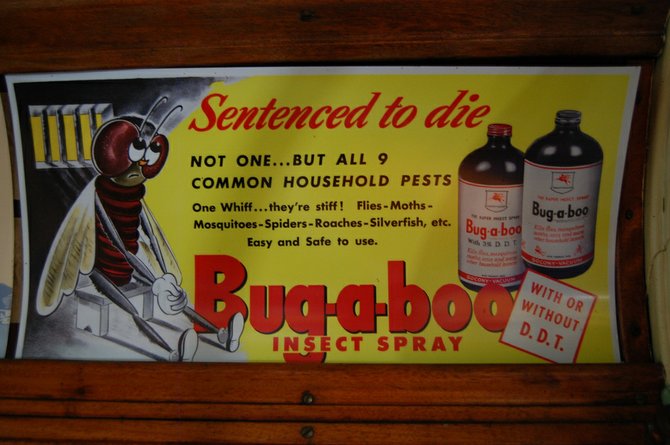

A widely used insecticide, DDT was banned in the United States in 1972 because it was building up in the environment. It is still used in Africa to combat malaria-infected mosquitoes. Photo by Courtesy Flickr/Kevin Krejci

Women exposed before birth to the banned pesticide DDT may have a greater risk of developing high blood pressure later in life, according to a study published today.

The study of San Francisco Bay Area women is the first to link DDT exposure in the womb to hypertension, which raises the risk of stroke and heart disease.

A widely used insecticide, DDT was banned in the United States in 1972 because it was building up in the environment. It is still used in Africa to combat malaria-infected mosquitoes.

"Our findings suggest that DDT may be targeting the system in the body that keeps blood pressure under control," said Michele La Merrill, a toxicologist at the University of California, Davis and lead author of the study published today in Environmental Health Perspectives.

In previous research, pesticide applicators with high blood pressure had higher DDT exposures than those with healthy blood pressure. Research also has suggested that DDT interferes with hormones, and it has been linked to decreased fertility, preterm delivery and diabetes.

In the new study, more than 500 women born between 1959 and 1967 participated. They were the daughters of more than 15,000 women from the Oakland area who were recruited by scientists to investigate how environmental exposures, even those that occur before birth, can affect health over a lifetime.

Because DDT can pass to the child through the placenta, the blood of the mothers, collected shortly before or after birth, served as a proxy for fetal exposure.

Several decades later, 111 of the daughters, 21 percent, reported having been diagnosed with hypertension.

Overall, the women in the highest two-thirds of prenatal DDT exposure were 2.5 to 3.6 times more likely to develop high blood pressure before age 50 than women in the lowest one-third of exposure.

"We are now seeing the potential long-term health consequences of introducing chemicals whose safety we know very little about," said Jonathan Chevrier, an environmental health scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, who did not participate in the new study.

Almost one-third of adult U.S. women have hypertension, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence in postmenopausal women is much greater than in premenopausal women.

The researchers found that the association between DDT and high blood pressure held after accounting for some factors known to raise the risk of hypertension, including age, race, body mass and diabetes status.

However, it is unclear how factors they did not test, such as how much salt a person eats, may have affected the findings.

It also is impossible to know whether some women had undiagnosed high blood pressure or how blood pressure levels differed across exposure groups.

"The degree of hypertension matters in terms of clinical significance, so from a clinical perspective it's hard to say anything about the relative importance of the findings," said Dr. Ted Schettler, science director of the Science and Environmental Health Network, a non-profit organization.

However, he added, "anything that raises the blood pressure of an entire population, even a small amount, can have large public health consequences."

DDT breaks down slowly, so most people alive today have traces in their bodies, and it remains in the environment and the food web.

"Each of us carries with us this history of past exposures," said Barbara Cohn, director of the Oakland-based study group.

While the findings are thought-provoking, we have no control over our past exposures, said Dr. Keith Ferdinand, a cardiologist at Tulane University in New Orleans.

"We must continue to focus on risk factors that are modifiable, including obesity, sedentary lifestyle and socioeconomic stress," he said.