On her first visit with me a few weeks ago, Mrs. Johnson, a 32-year-old schoolteacher, announced that she had a condition that "sounds like fibro-something."

"I am certain that I have it, because I saw the commercial," she said, self-diagnosing her fatigue, decreased sleep, pain in multiple joints and morning stiffness based on a 30-second ad.

I told her she was most likely referring to fibromyalgia. Johnson told me that she needed the medication on the commercial. She said it started with an L, but she could not remember the exact name.

"Could it be Lyrica?" I asked?

Excitedly, she stated firmly that it was the medication she needed and asked me for a prescription for it.

Many patients come to my office with pages of print-outs from the Internet, results from their searches of medical conditions and symptoms.

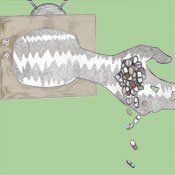

At times, patients don't want to "waste" their time providing detailed histories or doing tests, they just want the medications suggested by the pharmaceutical companies that sponsor many of their Internet sources and buy advertising time on TV.

Dr. Ray D. Strand wrote in "Death by Prescription: The Shocking Truth Behind an Overmedicated Nation" (Thomas Nelson, 2006, $11.99), that there is about a 70-percent chance that a physician will prescribe a patient-requested medication if that patient recites the specific symptoms in the drug's commercial.

During the 1990s, direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical drug advertising increased at a compounded-annually rate of 30 percent, according to Ian Morrison's book, "Health Care in the New Millennium: Vision, Values, and Leadership" (Jossey-Bass, 2002, $44). By 1995, drug companies had tripled the amount of money they formerly allotted to consumer-directed advertising, writes Gary Null in "Death by Medicine" (Axios Press, 2011, $12).

Pharmaceutical advertising has grown to the level of pop culture. Drug advertising campaigns are executed by ad agency people highly trained in the art of persuasion.

A commercial features a patient with social anxiety, for example, sadly looking through a window at a group having a party. Everyone inside looks happy, while the patient outside looks miserable. Of course, once the patient has taken the advertised medication, she is able to knock on the door, go in and be part of the festivities. The commercial then lists the side effects of the medication in a fast-speaking and nearly inaudible voice-over, while distracting the viewer by showing the formerly miserable patient having the time of her life. The message is clear: "Take our pill, and you'll be well and happy."

Ad agencies know it's effective to play on our legitimate fears of illness and mortality. For hypochondriacs, those fears are already heightened. Constant fear that minor bodily symptoms may indicate serious illness, endless self-examination and self-diagnosis, and a preoccupation with his or her body characterize a hypochondriac, though a true clinical diagnosis includes other requirements. Most of us have some symptoms of this disorder, and pharmaceutical companies take advantage of this. Physicians, however, can help.

My training gave me the skills to determine what important tests my patients should have to find or rule out medical conditions for many of their symptoms. This can include tests for certain forms of cancer, diabetes, heart disease and other serious ailments. In many cases, I must be prepared to refer a patient to a specialist for more detailed testing. Sometimes, I need to refer a patient to a psychologist for a diagnosis and proper treatment of true hypochondria, instead of simply prescribing what could be unnecessary and potentially dangerous medications without a proper work up—just because a patient asks for it.

'Mostly All in the Mind'

Health-care marketing campaigns are designed to increase negative thoughts and anxiety about having certain physical or mental illnesses, but the truth of the matter is that we all, in some way, have a tendency to catastrophize from time to time, thinking the worst will happen. The majority of people, though, trust an expert's opinion when told it isn't true.

For some individuals, a headache or runny nose is a sure sign of bad news, even signaling imminent death, and no positive diagnostic test can assure them otherwise. Their fears and worries cloud reality and interfere with their daily lives.

Technically, a hypochondriac, or a person who suffers from hypochondriasis disorder, is an individual who believes his or her physical symptoms are signs of a serious illness even when there is no medical evidence to support the presence of an illness, according to the "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders." It is classified as a somatoform disorder, or one that includes the experience of physical symptoms. The disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 1 percent to 5 percent in the United States and occurs equally in males and females.

It's important to note that individuals with this disorder do not intentionally make up or fake their symptoms; they're not malingerers. They can't control their physical symptoms.

The mind-and-body connection is powerful. We can convince ourselves that we're physically ill, and our bodies will react appropriately, providing the symptoms that confirm our mental machinations. The way people with hypochondria think about their physical symptoms make them more likely to have this condition. As they focus on and worry about physical sensations, the cycle begins and eventually may turn into extreme anxiety.

Most individuals diagnosed with hypochondriasis struggle with anxiety, depression or both. When an individual is constantly anxious about having an illness and his or her anxiety levels go up, stress levels also constantly increase. When anxiety and stress intermingle, it can produce physical symptoms such as headaches and stomach problems, causing mild to severe pain. And the cycle continues.

Most of us have worried at some point or another that a small physical symptom, such as a cough, could be a sign of a serious illness or disease. This is not hypochondriasis. However, if a preoccupying fear of doom or having a disease or illness lasts for longer than six months, the individual may be suffering from hypochondriasis disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

If you think you or a family member may be experiencing symptoms of hypochondriasis, consult with your family physician or a mental-health professional. As with all psychiatric disorders, hypochondriasis disorder demands creative, in-depth treatment planning by a team that includes primary-care physicians and mental-health professionals.