If you press your ear up against the western literary canon, you can hear a million women whispering—but for the most part, you won't be able to make out the words. The past century has begun to chip away at the silence, but the lives of women—and the emotional lives of men—are still shelved away under the heading of "confessional literature," as if all honest literature didn't have something to confess, while the label "narrative nonfiction" gets slapped on heroes who hide their scars and write about struggles that don't remind us quite so much of ourselves.

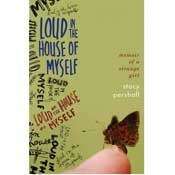

Stacy Pershall's "Loud in the House of Myself: Memoir of a Strange Girl" (Norton, 2011, $25) is the story of somebody who survived anorexia and learned to live with borderline personality disorder, but that makes it sound like a different book than it is. Pershall's description of the support community surrounding Susannah, a little girl with Apert syndrome (a hereditary disorder characterized by craniofacial malformations and fusing of fingers and toes), whose face and story were printed on posters all over her small hometown of Prairie Grove, Ark., is a good illustration of what her own story isn't: "inspiring" in any kind of safe, affirming way.

Pershall is clearly out to change the world with this book, and readers who see themselves in her story and emotionally commit themselves to it will find themselves challenged in a way they might not have anticipated. This is the literary equivalent to an exfoliant scrub, a book that could have a warning label that reads "warning: contains nudity (your own)."

That isn't to say that there's no warmth and gentleness in it. Pershall takes her title from Anne Sexton's poem "Double Image," which speaks of "a small milky mouse / of a girl, already loved, already loud in the house of herself." Her story of how she became so loud—how the girl who hid in a closet and wrote insults on her body with a black magic marker grew up to become a powerful and wise adult—is punctuated by descriptions of people around her that are both sympathetic and unforgiving.

Pershall advocates dialectical behavioral therapy as a treatment for BPD. One of the hallmarks of the therapy is the way it undermines the "alternating ... extremes of idealization and devaluation" that characterize the stereotypical borderline personality's assessment of people. Until I read this book, I did not realize that good writing is to a great extent about rejecting the same kind of simplistic, black-and-white thinking.

Every major character in Pershall's story comes through as complex. She undermines any attempts to describe herself and the people she loves as if they were saints, or the people who hurt her as if they were demons. In a heroes-and-villains world that celebrates melodrama, that kind of honesty is more rare than it sounds. (Nowhere does this three-dimensional portrayal stand out more than in her description of her mother, one of the central heroes of the book—but maybe also one of its central villains, depending on how you're reading it. Lovable and flawed, in either case.)

The author uses her story to advocate for people (nearly all of them girls and women) who have borderline personality disorder or anorexia, and the epilogue makes a series of policy suggestions that seem long overdue. Health-insurance access shouldn't determine whether or not people get the psychopharmaceuticals they need; insurance companies should not dictate whether and how Axis II personality disorders are treated; girls and women with BPD should not be written off.

"For so long," Pershall writes, "BPD was seen as a 'garbage can' diagnosis, a name—for lack of a better one—for the patients who showed up frequently in emergency rooms and therapists' office, chronically threatening suicide in response to the normal vicissitudes of life."

A century ago, "hysteria" was the garbage-can diagnosis. Garbage-can diagnoses are effective ways to shoehorn poorly understood cases away from treatment, but that's not what our mental-health system is for, and Pershall vividly describes the consequences of that approach.

As much as the book is "about" BPD and anorexia, though, it's also about deviance—the freedom to be creative; the freedom to be who we are; the sham we buy into when we allow others to judge us.

Pershall, who wrote on her body with magic markers when she was young, has now made her body a more permanent canvas for a growing number of tattoos that represent her values and her story. This book is a tattoo, too—beautiful, personal, painful—and it has a lot to tell you.