Behind the Silver Slipper Casino in Bay St. Louis, a fleet of commercial fishing boats sits quietly before sunrise on April 30. Even though it's the last day of oyster season, only a few fishermen are at the Bayou Caddy Marina. A strong 25-mile-per-hour wind is pushing a massive oil spill the size of Rhode Island onto the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Several fishermen fear that this could be the last time that they will have a chance to catch a harvest but don't want to risk damaging their boats in the rough conditions.

Ten days earlier, an explosion burned and sank the British Petroleum-owned and Transocean-operated Deepwater Horizon oil-drilling rig, killing 11 members of the 126-member crew. The crew was just the beginning, however, and they only comprised the human casualties. The rig is located approximately 40 miles off the Louisiana coast, but the resulting oil jetting up out of the rig's severed well pipe is crossing that distance quickly.

Today a thin film of grease floats on the waves knocking against the Mississippi River Delta, sticking to everything it touches, cutting off the oxygen, killing. And more oil is coming.

"We are worried about what is going to happen in the long run," Eugene Boles, a captain who canceled his oyster trip, says. "Mississippi already has a high rate of unemployment. … Everyone on these boats represents a couple families; people don't realize that."

Boles, a native of Biloxi, says the 2010 oyster season in Mississippi has been hard enough as it is. Heavy rainfall and high bacteria count forced the Department of Marine Resources to shut down the state's 17 oyster reefs several times, including three consecutive weeks last December. If the oil makes its way to the Coast, Boles said he hoped to find work with the clean-up crew.

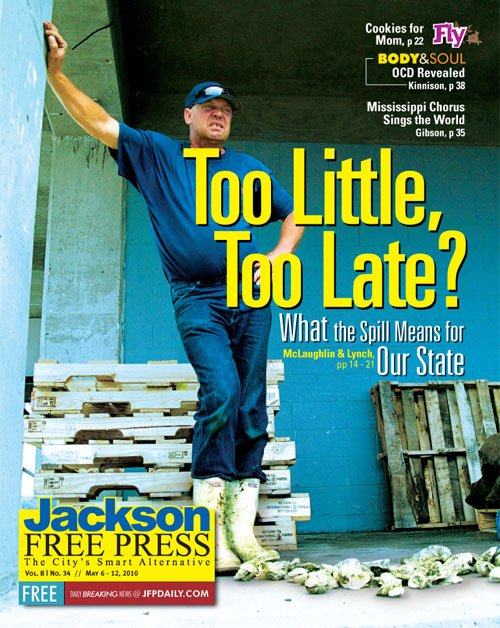

As the sun rises, Captain Giles Lanasa arrives at the dock, undeterred by the weather. His rust-stained drudge boat with the words "My Sandra" hand-painted on the side, bears its share of bruises. The front rail dangles off the boat above the water, and various nicks and scuffs adorn the outside.

Lanasa and his crew, Renee "Toby" Barletter and Steven Barlet, aren't about to let a little wind stop them. "You may be in for a rough ride, so make sure you hold on tight," Barletter tells a Jackson Free Press reporter and photographer. Lanasa pulls out of the bayou with one hand on an old wooden steering wheel while he takes drags off his cigarette with the other. Lanasa, a native of Louisiana, is a fourth-generation fisherman who has been working on a boat full time since he was 15 years old.

As we head to the Saint Stanislaus reef near the Pass Christian bridge, Lanasa points to a white trash can in the corner. "Throwing up overboard is considered illegal discharge, and the boat will be fined $500," he says. "If you need to throw up, do it there."

Barletter appears in the cabin carrying a small portable toilet.

"It's brand new," he says. "All you need is a little water to flush it out, and don't worry—we'll give you privacy."

A few minutes later, the photographer hugs the trash can and vomits as waves violently toss the boat back and forth. Lanasa smiles and hands him a Coke.

A strip of gray duct tape is attached on the cabin's wall with the following inscription: "M-9, T-14, W-15, T-25." This is how Lanasa keeps track of each day's harvest. The Department of Marine Resources limits fishermen to 25 sacks per trip, and each sack weighs about 105 pounds. He sells each sack for $30 back at the marina, where a distributor then takes the oysters to retailers.

Lanasa says he could make more money if he "cut the middle man out" and took the oysters to the retailers himself. But to do so, he would need a refrigerated truck.

When the boat arrives at the Saint Stanislaus reef, the two deck hands lower the dredge into the water. Lanasa then makes smooth and precise circles with the boat, careful not to go too fast or too slow. The dredge, a cast-iron basket attached to a toothed bar, scrapes the bottom of the reef; an automatic crank raises the dredge up by a chain. Oysters fall onto a table, and the deck hands fiercely break the oysters off clusters of barnacles and other shells using a culling hammer. Barletter and Barlet fill burlap sacks with the oysters, repeating the process for four hours without taking a break.

Lanasa is quick to site DMR regulations and keeps a watchful eye for violations.

Last year, he received a $500 fine for not returning required paperwork stating the number of people on board and the amount of oysters caught.

"You lose three days worth of work right there," he says.

"You lose a day's catch, get a $500 fine and have to take a day off to go to court."

Lanasa can't afford another fine, especially because this year's season has been one of the worst he can remember. He pays $100 a day in fuel costs, and pays the deckhands $100 each per day. On days that he doesn't meet the 25-sack quota, he feels the pinch.

"When it's good it's good, and when it's bad it's bad," he says.

For the first few hours of the trip, Lanasa is quiet about the potential impact of the oil spill on his livelihood.

As oyster boats circle the reef, the United States Coast Guard places booms under the CSX train trestle over the St. Louis Bay a few hundred feet away.

Oil- Rigged Politics

News media insisted on using words like "might" and "possibly" during the first week after the explosion when describing the likelihood of the oil slick's contact with the shores of the Gulf Coast.

They were being optimistic.

By April 29, federal officials upgraded BP's initial assessment of the oil flow gushing into the Gulf to about 5,000 barrels, or 200,000 gallons, a day. At that rate, the spill could surpass the damage of the worst recorded oil spill in U.S. history.

In 1989, a grounded tanker, the Exxon Valdez dumped 11 million gallons of crude oil in Alaska's Prince William Sound, costing $2.1 billion to clean.

At the end of last week, it was clear that this was not a spill comparable to the sludge dumping out of a stricken tanker. A leaking oil tanker stops leaking oil when the tank runs dry, but this is oil straight out of the black heart of the Carboniferous Age. This well could go on for a long time, containing some of the most prolific sweet crude available in the Gulf Coast.

British Petroleum told reporters last week that they predicted having the leak stopped within three months. At the current rate, that's 18 million gallons, surpassing the 11 million gallons bequeathed by Exxon to Prince William Sound in 1989, costing $2.1 billion to clean up.

Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano declared the spill from the oil well of "national significance," at an April 29 press conference, and said 16 federal agencies are already involved and more U.S. resources on the way to contain the spill. The U.S. government set up command centers on the Gulf Coast, and Interior Secretary Ken Salazar has suddenly ordered inspections of all deepwater rigs in the Gulf. "We expect industry to be fully complying with the law," Deputy Interior Secretary David Hayes told reporters at the April 29 briefing.

But laws are only as good as the legislators that make them, said Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen's Energy Program, and legislators don't always see the potential oil spill on the horizon until it's between their toes. The devastated $700 million BP rig could have had a remote safety valve that might have cut off the oil before it went down, Slocum told the Jackson Free Press. The valves can be found on oil rigs off the coast of Norway and other countries, but no U.S. law requires them in U.S. waters.

"That's because BP actively fought these regulation because they said it would cost too much. That is the knee-jerk reaction by any industry when faced with government regulation trying to address workplace safety or environmental protection," Slocum said. "They say this regulation costs too much, and now we're learning tragically here what comes of that."

The lax requirement serves no good interest, Slocum said, adding that British Petroleum's safety record is abysmal.

Gov. Haley Barbour downplayed the oil's threat to the Coast during a press conference in Gulfport Friday. He assured the public that as the responsible party, BP would pay for all cleanup efforts and was doing everything in its power to stop the oil well from leaking.

"About 60 percent of the spill is sheen; it's a microscopic film on the surface. It's light, and its exposure to the air and the waves dissolve it," he said.

"I want to assure people on the Coast that everything is being done to keep the oil slick from landing on the barrier islands or getting into the sound," he added.

Barbour, a long-time proponent of offshore drilling, said 70,000 feet of boom would be in place to keep a "light sheen" from impacting the Coast. He said he was "optimistic" that the sheen would pass over oyster beds and would have little impact on marine life, claiming that most marine animals would "swim away" from the oil.

The governor ended the press conference saying that his "position hasn't changed" on domestic drilling.

Twelve Miles Isn't Enough

The next day, Mississippi Sierra Club Director Louie Miller criticized Barbour's response to the situation during a press conference, calling the oil spill "America's Chernobyl" after the 1986 nuclear power plant disaster in Ukraine.

"This is going to destroy the Gulf Coast as we know it," Miller said. "We are not getting the response that we asked for. The governor yesterday took what I thought was a lackadaisical attitude, calling it a little sheen on the water."

Last weekend Miller reunited with members from the 12-Mile South Coalition, a group that successfully fought to stave off the expansion of oil and gas drilling rigs within sight of the Biloxi and Gulfport beaches in 2005. The members, now called the Better Mississippi Group, called on a better government response to prevent the oil from reaching the shoreline. Miller said he now believes that 12 miles isn't far enough, or 80 miles for that matter.

"The burning is not working. The booms are not working," he said. "What we are doing is asking Obama to militarize the response. I think this is a time that the administration takes a serious look at a clean energy future. If there were windmills out there 12 miles south, if they broke, we wouldn't be in an economic disaster."

U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran, one of Mississippi's most powerful Republicans, inserted language in an April 2005 emergency military spending and tsunami relief bill ordering the Department of Interior to allow exploration in the Gulf Islands National Seashore encompassing the barrier islands, and allow directional drilling beneath it. Cochran's language sweetened the deal for Mississippi by granting it the mineral rights to the territory, but also gave energy companies like Exxon-Mobil the ability to seismicly explore for oil and gas inside the park.

Environmentalists reacted harshly, pointing out that the park contains the state's largest population of bottlenose dolphins. Research shows sea mammals like dolphins, which use sonar for navigation and hunting, can suffer injury to their sensitive ears from the resultant shock waves of seismic exploration.

Cochran's office wrote in 2005 that he inserted the language to "remove the cloud of confusion over who owns the mineral rights to the Mississippi barrier islands." His office also fluffed over the insertion, arguing that the language would allow "the National Park Service to continue its good work in preserving the natural and historic features of the Gulf Island National Seashore."

The timeliness of the inserted language drew suspicion because it followed a state law, approved by the Mississippi Legislature in 2004, allowing the state to shift the responsibility for regulating offshore exploration and seismic testing from the more tightly regulated Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality to the anything-but-regulated—and very pro-business—Mississippi Development Authority, which is completely under the control of Republican Gov. Haley Barbour. Barbour, by his own statements, was a fan of "drill, baby, drill" long before it became a 2008 politicalslogan.

Cochran's timing prompted many members of the state's environmental community to suspect Barbour had pushed Cochran into making the insertion. Barbour never admitted to the accusation, but remains an advocate of more domestic drilling to offset fuel imports from other nations.

The Jackson Free Press was down in Gulfport covering the 12-Mile South Coalition's August 2005 anti-drill rally at the Coast Coliseum and Convention Center days before Katrina came ashore and made the fight a moot point.

Nothing has legally changed since 2005: The state and federal language still make rig expansion into the Barrier Islands possible, and tourism industry and environmental advocates are still wary of gas and oil rigs sticking their probes into federal park waters.

But attitudes regarding offshore oil prospecting may be about to change.

A Call to Action

Captain Louis Skrmetta, owner and operator of Gulfport's Ship Island Excursions, which runs daily trips out to Mississippi's Barrier Islands, invited the press and activists on his charter boat Saturday to call attention to the local tourism and fishing industry that will be impacted by the spill.

"My fear is that it will be a miserable, slow kind of death for the water," Skrmetta told the Jackson Free Press. "This, I think, could spell the painful death of multiple industries in the area. Tourists don't come to sludge-covered waters. They don't come to look at empty bird nests because all the chicks have died and their parents have starved or moved on because of oil covering the area and killing the fish. Only reporters come to see that kind of thing."

Skrmetta speaks with a fearful sense of loss when he talks of the inbound sea of oil constantly flooding the northern area of the Mississippi Gulf and his precious Barrier Islands. Skrmetta, as a representative of the tourism industry, joined with the casino lobby in 2005 to press the importance of keeping the skeletal-looking iron lumps out of the viewable range of patrons on the beach and visitors to the Barrier Islands.

The captain wiped tears away from his face as he discussed the potential for the oil spill to destroy the Coast's entire way of life. Skrmetta's great-grandfather was an oyster and shrimp boat captain who spent summers taking tourists to Ship Island. He fears there will be no future in the business for his sons or grandchildren.

At age 23, while working as a deckhand on an oil-supply ship out of Louisiana, Skrmetta remembers when the ship accidently spilled 8,000 gallons of oil into the Gulf in the middle of the night.

"It wasn't reported, it wasn't logged, and that used to be common," he said. "Things have changed. … It was in the 1970s. But it shows you the types of things that can happen."

After that incident, Skrmetta left the supply ship and decided to join thefamily business.

Skrmetta called on the government or BP to invest in HESCO container units, a cellular wall system made of rebar and a geotextile liner that could stop the oil from seeping into the coastline and marshes. He said that if the wall system was filled with sand and a solution called C.I.Agent that turns oil into an inert substance, it could drastically reduce the impact of the oil on the Coast and cost less in the long run.

BP said Sunday, however, that the company will address cleanup efforts when the spill reaches the coastline, but will continue to disperse booms. The governor hasn't made any indication that state funds will be used for cleanup efforts.

Disaster in the Making

Public Citizen released an April 29, 2010, statement pointing out that BP has paid $485 million in fines and settlements to the U.S. government for environmental crimes, neglect of worker safety and even for manipulating the U.S. energy market.

In 2005, for example, 15 workers died in an explosion at a BP refinery in Texas. The company paid $87.4 million to the government last year—the biggest settlement in Occupational Safety and Health Administration history—for willful negligence in the months leading up to the explosion, as well as an extra $50 million to the Department of Justice.

As recently as this past March, the company paid OSHA $3 million for 42 safety violations at an Ohio refinery. Back in 2006, the company paid $20 million to settle allegations that the company violated the Clean Water Act after neglecting one of its major oil pipelines in Alaska's Prudhoe Bay.

"But then there was the market manipulation stuff," Slocum said. "They paid a $303 million fine to the federal government for single-handedly cornering the propane market and another $20 million for helping to manipulate the electricity markets in California, along with ENRON. This is a company with a track record for repeat violations of federal laws and statutes. If this was an individual, their three strikes would have happened a long time ago and they'd be in jail. But it's a corporation, and they operate by a different set of rules, and they continue to operate, and it's really quite tragic."

The $485 million in fines and settlements over the last five years hardly make a dent when the company is raking in the kind of money it generates. London business periodical The Street reported April 27 that BP, which is the second-largest oil company in Europe, reported profits in the first quarter of $6.08 billion compared to year-earlier profits of $2.56 billion.

BP's American press office said it began drilling a relief well to intercept the oil gushing out of the ruptured well last Sunday. The company is injecting dispersants into the oil flow near the main leak on the seabed in an attempt to break up oil accumulation and degrade them. The company is also building a containment canopy to lower over the leak and connect a pipe, to channel the flow of oil to the surface where it can be safely stored on a vessel.

BP said May 4 that it expects to install the first canopy within a week. Using the dispersants under the water is a new tactic, and biologists fear the chemicals could be harmful to marine life. Last week, BP said it could take as long as 90 days to plug the well, which is now leaking approximately 200,000 gallons of oil into the gulf per day.

It's not hard to see the oil industry's influence in the way politics comes together in America. Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., echoed the very words of the industry when she complained last year that the proposed Clean Air Act should not be applied to carbon-dioxide emissions, and collaborated with Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, last year to keep it that way.

"To regulate carbon emissions with the Clean Air Act would be to jam a square peg into a round hole," Landrieu told the Times-Picayune in January. "This act is a blunt instrument not suited to the job. I fear that the result would be poorly designed regulations that damage our economy, lead to great investment uncertainty, and not do enough to enhance energy security and reduce the risks of climate change."

It's not the first time she echoed the desire of the industry. Last year, Landrieu—whose state is getting a heaping helping of oil-based muck along its wetland shoreline this week—signed onto Senate Bill 1517, which also allowed drilling near Pensacola, Fla., and an area off the coast of Alabama.

In 2006, Landrieu joined forces with Sen. Pete Domenici, R-N.M., to push through the "Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act," which opened 8.3 million acres of the Gulf Coast for drilling. This bill marked the first time in a quarter-century that a portion of the outer continental shelf had been opened to energy exploration, and made it possible to dig an oil-filled hole in the middle of the nation's shrimp and oyster industry.

Government watchdog group Open Secrets.org reveals that the oil and gas lobby contributed $364,950 to her campaign between 2005 and the 2010 election year.

Even President Barack Obama, who campaigned against the idea of opening new U.S. waters to oil and gas prospecting as wasteful and pointless, caved to the industry and their supporters in the House and Senate this year, proposing a compromise that tickles oil companies and domestic drilling advocates, while sending environmentalists and the seafood industry into a tizzy.

Obama suggested that the long-time moratorium on oil exploration along the East Coast from northern Delaware to the coast of Florida should be canceled. His plan would allow no oil or gas activity along the coastline north from New Jersey or along the Pacific Coast, from the Canadian border down to Mexico.

The plan, which covers 2012 through 2017, opens the coasts of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and part of Florida's eastern seaboard to exploration and possible drilling. It also opens the drilling door to 130 million acres of the sensitive northern coast of Alaska in the Chuckchi and Beaufort Seas.

Oil And Your Supper

As the news continues to report oil moving into the Louisiana wetlands, it's hard to hear many "drill, baby, drill" chants emanating from offshore-drilling proponents there. The people who depend upon those wetlands for their livelihoods, however, are just getting cranked up.

Gulf Oyster Industry Council member and Bay St. Louis oyster fisherman Keath Ladner says he fears the worst.

"The oyster can't get up and move like the shrimp or the fish, so all he can do is wait for the oil to come floating in over his head. He's a filter feeder, so he'll get contaminated. If he gets too much, it'll kill him," Ladner said, while adding that the industry already spent much of the season closed down because of the heavy rains pounding the area.

This year, torrential rains spilled into the Mississippi River, flooding the oyster reefs with a surplus of fresh water, which could lead to bacterial infection in the mollusks. Ladner said an oyster can handle complete freshwater for about 20 days and stay alive, but not without the possibility of collecting too much bacteria. Nobody needs to eat a raw oyster with a bacterial infection, so government regulators closed down oystering for much of the season, taking a toll on business. Now, however, the industry must deal with not-so-sweet crude slipping in silently from the deep sea.

Jessie Pettis, co-owner of D.L. Pettis & Son Seafood Shop in Moss Point, said she expected the oyster industry to take huge losses if the oil made it all the way to the oyster reefs.

"This oil spill could put the industry in Mississippi completely out of business," Pettis told the Jackson Free Press. "We've already been shutting down for most of the season because of all the bacterial infection in the oysters. It's been rough the whole year. My husband was born and raised on catching oysters, but we didn't even have oysters this Christmas. This thing here, this thing could kill what's left of the business."

The U.S. marine aquaculture industry is relatively small compared with overall world aquaculture production.

Total U.S. production is approximately $1 billion annually, compared to world aquaculture production of about $70 billion. However, the largest single sector of the U.S. industry is mollusk and shellfish culture (oysters, clams and mussels), which accounts for about two-thirds of total U.S. production, followed by salmon (about 25 percent) and shrimp (about 10 percent).

Mississippi's oyster fishery is still recovering from the devastation of 90 percent to 95 percent of the oysters by Hurricane Katrina, but the total value of the output of economic goods directly produced by the Mississippi commercial oyster industry reached more than $2.76 million.

That figure generates a total economic impact of $12.17 million for the state, as the oysters change hands from boatman to waiter. The industry created 99 jobs and generated employee compensation, proprietor income and property income amounting to $2.97 million, according to Ben Posadas, associate professor of economics at Mississippi State University.

Louisiana, the nation's most productive state for oysters, produces a third of all oysters produced in the U.S. with 13 million pounds of oysters each year, valued at about $35 million to $40 million in dockside value. Follow that $35 million or so through the marketplace, and it comes out to be more than a $300 million impact for the state. It's a significant part of the economy, but those numbers in both Louisiana and Mississippi could change soon courtesy of British Petroleum.

"It depends upon the toxicity of the oil," said Patrick Banks, oyster program manager with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

"There are fractions of the oil that are more toxic than the others. The fractions that are water-soluble … could easily get down to the oysters and contaminate them. But the good news is this oil has been mixed with millions of gallons of water before it reached our shorelines. I'm hoping it's so diluted it won't be quite as big of a problem, but I don't know this right yet."

The timing of the spill represents a challenge, Banks said, because the oysters are just now getting ready to spawn, which could affect oyster production for many generations to come: "The toxicity level can have a far-reaching impact on the reproductive ability of the adults and the health of the larvae as well."

The shrimp industry is a vital part of Mississippi's coastal development. Dockside value of Mississippi's annual shrimp harvest, according to National Marine Fisheries Service statistics, averages $30 million. Mississippi's annual commercial catch averages approximately 16.7 million pounds.

In 2007, early-season wholesale shrimp prices on the Mississippi coast averaged $1.15 a pound, compared to just 95 cents the previous year, despite competition from Asian distributors. The Mississippi Department of Marine Resources says the entire shrimp, oyster and seafood industry in Mississippi generated $205 million for the state in 2009. It was not willing to speculate how much seafood costs could go up as a result of deceased harvests resulting from hydrocarbon poisoning.

The problem of oil in the Gulf goes far beyond the price of the shrimp in your Popeye's basket, however.

The mouth of the Mississippi River Delta and the wetlands behind it had been growing for thousands of years as the Mississippi River carried its load of sediment down from the North American continent. In the 1930s, the area looked enough like a jungle to serve as a setting for Tarzan movies. The region has been sinking for 100 years, however, as human construction put an end to the seasonal flooding of the Mississippi River and the scooping of river sediment that followed. Between 1974 and 1990 the land-loss rate in the Mississippi River Delta Basin averaged 1,072 acres per year, or 1.69 percent of existing land area. Between the mid-1950s and 1974, the estimated land loss rate for the basin was 2,890 acres per year. The total land area lost in this basin over the last 60 years has been approximately 113,300 acres.

Despite the shrinking territory, more than 260 species of birds inhabit the area, including skimmers, plovers and terns. Other migrating birds, including Sanderlings, drop by on their trip from the Arctic to South America. Osprey, pelicans and bald eagles also inhabit the area, but the pelican nesting season starts in the area within two weeks, said Mark LaSalle with Audubon Mississippi's Moss Point field office.

"I've never personally experienced something this devastating before," LaSalle told the Jackson Free Press. "Our main concern is that any oil hitting the beaches or marshes would impact the upcoming breeding season of a lot of birds. Many of them are already sitting out there. We have record numbers of pelicans getting ready for mating season. We're on the cusp of the breeding season for a wide range of birds. … These birds are seabirds that depend on shrimp and fish, which may already be impacted (by the oil)."

The human feeders certainly appear convinced that the shrimp and oysters are doomed. Ladner said regulators are allowing shrimpers and oyster boats to scour the bay in an attempt to nab all the viable shrimp and fish they can—as if the catch will not be there tomorrow, and on May 3, NOAA closed commercial fishing in the spill-affected area, from Louisiana to east of Pensacola Bay in Florida in U.S. Gulf waters.

Spill, Baby, Spill

Slocum said advocates of these industries and the environment will likely bring a change of heart to the national attitude toward oil speculation in the Gulf. He cited Landrieu as an example.

"Mary Landrieu is a Democrat from Louisiana who is usually very open about prioritizing the needs of the oil and gas sector. I understand they have a presence in her state, but there are also a lot of fishermen in her state, and a lot of people who enjoy a pristine coastal ecosystem that is going to be directly threatened by this," Slocum said. "That's the issue we have. We're not trying to say oil companies are evil, but sometimes their economic interests are prioritized above competing economic interests of people living in an area that will be negatively impacted by mishaps and negligence."

Miller said the lesson in oil drilling oversight is coming too late, as it always does, in his opinion.

"It's ugly. It's absolutely ugly. This country doesn't learn anything unless it's in a catastrophic situation and unfortunately that's what we're about to witness," Miller said in an April 28 interview.

"There's a reason (Florida Gov.) Charlie Crist said basically ‘f*ck drilling' after getting off a fly-over of the spreading oil slick. He was soft-pedaling originally on the issue. He was saying (he was OK with drilling in Florida water) if it's far enough away and clean enough. We've been lulled into a false sense of security by oil companies and their minion cheerleaders like Newt Gingrich and Sarah, ‘drill, baby, drill,' Palin, and we're fixing to extend an invitation to Haley Barbour to bring his buddies down here and get a load of this."

Miller compared BP's and the federal government's attempt to corral the floating muck and burn it off to "pissing on a brush fire."

"Good luck," he said. "You've got 200,000 gallons coming out at a time. There's no way you can burn it off. It's coming off 100 times the rate you can burn it off. The whole Obama administration, because they're listening to BP, has completely underestimated the gravity of this situation, and it is turning into a Katrina-like situation where they go ‘oh, the levee broke, so we're throwing some sand bags on it,' and the next thing you know 80 percent of fricking New Orleans is under water.

"They're not sending the resources. They're just now beginning to getting the dispersants and the skimmers, and that's really the only damn thing they're doing."

Miller thought for a moment, then added: "Personally, I want (the oil) to hit the panhandle of Florida where all the Republicans have their beach houses and can go out and step on tar balls for the next five years and wonder how this happened. Of course, it happened, they'll say, because Obama's in office."

Slocum agreed that the Obama administration may have not been "on top of this the way they should have been."

"It's unclear as to whether the responsibility lies with the president or the companies involved. With Katrina it was very clear that there were failures from the local level all the way up to federal government, and they didn't respond quickly enough to the crisis when most folks saw it coming from a mile away. I think we need to have an investigation. (The U.S. Department of Interior's Minerals Management Service), which has direct oversight of these offshore rigs, claims they were just out to that same rig a month ago. We need to make sure if this was lax oversight or human mechanical error."

Slocum added that it did not appear Obama played a role in knocking down tough oil-drilling regulations, which he said happened during the Bush administration. He criticized the president for not reversing Bush's regulation removal, however.

"Obviously, there was not a rule-making in the works to undo some of these decisions from the Bush era, but I think calling this Obama's Katrina would be premature. But there's no question that we need a full investigation to determine how this occurred and where the lapses were," Slocum said. "The Coast Guard agreed that the spill was five times less than what they said more recently. What's the reason for that discrepancy, incompetence from the government or what?"

The federal government is already painting a target on BP. During the same press conference in which Napolitano admitted to the new figure on the oil-spill rate, she was also quick to inform reporters that BP will have to pay the costs associated with an oil spill, as required by law. Napolitano said she and other administration officials are touring the region.

Bloomberg reported Aug. 29 that Carol Browner, the president's adviser for energy and climate change, said the administration is putting government resources into helping stem pollution and has asked BP to consult with the Department of Defense to determine whether the military has any kind of technology that is useful in containing the spill that may be better than what the private sector has to offer.

But the government, Napolitano emphasized, will make sure the taxpayers are reimbursed. BP is required to cover the spill by law, according to the 1990 Oil Pollution Act, drafted after the Exxon Valdez.

The Exxon Valdez spill may prove an unfortunate test case on how far along human technology has come in cleaning up oceangoing sludge—which is still done with buckets and soap in many cases.

Pam Brodie, chairwoman of the Sierra Club of Alaska, said Exxon has been very good at fighting lawsuits in the Exxon Valdez affair, despite the disaster appearing to be a clear case of negligence. Joseph Hazelwood, the ship's captain, was legally intoxicated at the time, and handed the wheel to subordinates as it navigated rocky waters of Prince William Sound.

The state and federal government settled a lawsuit with the company out of court fairly quickly after the spill, for the amount of $1.1 billion, paid out over 10 years. It was a controversial decision, with the Sierra Club complaining at the time that the company was ultimately cheating the government and avoiding accounting for inflation over that 10-year period. That quick settlement, however, spared the government from going through the 20-year legal wrangle of fishermen and fish processing companies who filed a civil suit against the company for the same spill.

A federal jury in Anchorage found Exxon responsible for the damage in 1994, awarding $287 million in damages and $5 billion in punitive damages. Exxon successfully appealed that to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, arguing that the company had already paid the U.S. government a hefty amount of cash for the damage. The matter bounced back and forth between the U.S. District Court in Alaska and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, which in 2007 finally cut the punitive award to $2.5 billion. Eventually, the plaintiffs dragged the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which capped the punitive award at $507.5 million in a 5-3 ruling in 2008.

"It started out as a $5 billion settlement, but kept getting cut down and cut down. And then there was the question of whether Exxon owed interest on the settlement, and we're not even sure if that is completely settled at this point, but after 20 years it was a much, much smaller amount than people thought they were going to get," Brodie said.

Brodie said the fishing industry in Prince William Sound still hasn't recovered since the 1991 devastation.

"Fishing was a tremendously profitable industry at the time of the spill, and it has lost in value, but that may not be entirely a result of the spill," said Brodie, who worked with the Sierra Club in 1989 as clean-up workers pulled thousands of dead oil-covered animals from the devastated water. " … A lot of that also had to do with fish farms that lowered the price of salmon. It's like when Kennedy was assassinated when everything went wrong."

The oil, she said, is still there in places, even after 20 years: "Go to Prince William Sound, and it's stunningly beautiful. Tourism can't see the difference, but if people go kayaking, and they camp in the sheltered (beaches) and dig down in the sand for a foot, there's oil that seems unchanged for 20 years. Some species recovered very quickly, while others have taken longer."

Both Brodie and Slocum appeared convinced that the damage in the gulf will sway the nation's opinion to be in favor of more oversight for oil drilling, which would be a far jump from where public opinion has been for the last decade.

"We've got political rhetoric in this country that government is bad. Barack Obama was called, by reputable political leaders, a ‘socialist' for advocating a role for government in the economy, which is preposterous, but that's what it comes down to. It comes down to corporations who have a vested financial interest in having as weak a regulatory oversight over their operations as possible," Slocum said. "… It comes down to short-term financial benefits for the industry from lobbying Congress to avoid basic regulations, and the long-term costs to public safety and health. All of this could have been avoided if we had a political apparatus and a regulatory apparatus that was responsible, that was not swayed by nonsensical rhetoric that is just a front for corporate interests."

Learning to Adapt

Lanasa, like other fishermen on the Coast, has learned to adapt when tragedy strikes. During Hurricane Katrina he drove his boat 17 hours north on the Mississippi River. When he came back to Bay St. Louis he hoped to use his boat to clear debris out of the water but learned his boat didn't meet federal requirements for debris clean up. Since the oyster beds were badly damaged, he went to work at a shipyard as a welder for two years—a job he disliked.

"Here, I get to be my own boss," he says on his boat April 30. "I've got nobody to report to. I don't have to work hard so someone else can take all the credit."

As the sacks pile up on the back on the boat, Lanasa gets a phone call from a friend who says officials from DMR and The Department of Environmental Quality are meeting to determine if the oil has contaminated the oysters. If so, Lanasa would have to return his oysters to the reef.

He grows nervous at the prospect.

"I ain't going to dump them," he said defiantly. "Is the DMR going to reimburse me? Are they going to pay my deckhands for a full day's work?"

Since the oil spill, rumors abound about jobs for fishermen for clean-up efforts, potential wealth from joining a class-action lawsuit against BP and new regulations for fishing off the Gulf Coast. It isn't clear if the phone call is just another anxiety-filled rumor or a serious threat.

A few minutes later, however, Lanasa's friend calls again, telling him that he can keep the day's catch.

Satisfied with the news, Lanasa returns back to the marina with 25 sacks. A group of fishermen and deckhands greets him at the dock as he loads the sacks onto a conveyer belt for distribution. Barletter calls family members telling them to come pick up a sack. "Who knows when we'll see this many oysters again?" he says.

Even though oyster season is ending, Lanasa uses his boat for shrimping during the summers, and it's his sole source of income. He brushes off questions about the spill, saying, "There is no telling what will happen with that oil, only time will tell."

Previous Comments

- ID

- 157653

- Comment

It is clear that a lot of hard work went into this piece. Kudos!!!!

- Author

- J.T.

- Date

- 2010-05-05T20:58:07-06:00

- ID

- 157656

- Comment

Thank you for putting human faces, dreams and pain on this truly "too big to tell" story. I suppose a little sea sickness was a small price to pay for this timely and well written story.

- Author

- FrankMickens

- Date

- 2010-05-06T08:11:42-06:00

- ID

- 157669

- Comment

Let's not forget that the Minerals Management Service is still recovering from the disastrous free-for-all of the Bush years. The report says that eight officials in the royalty program accepted gifts from energy companies whose value exceeded limits set by ethics rules — including golf, ski and paintball outings; meals and drinks; and tickets to a Toby Keith concert, a Houston Texans football game and a Colorado Rockies baseball game. The investigation also concluded that several of the officials “frequently consumed alcohol at industry functions, had used cocaine and marijuana, and had sexual relationships with oil and gas company representatives.” The investigation separately found that the program’s manager mixed official and personal business. In sometimes lurid detail, the report also accuses him of having intimate relations with two subordinates, one of whom regularly sold him cocaine. The culture of the organization “appeared to be devoid of both the ethical standards and internal controls sufficient to protect the integrity of this vital revenue-producing program,” one report said. In nearly every area, the Bush administration gutted regulations and climbed into bed with industry, in this case literally.

- Author

- Brian C Johnson

- Date

- 2010-05-06T13:52:55-06:00