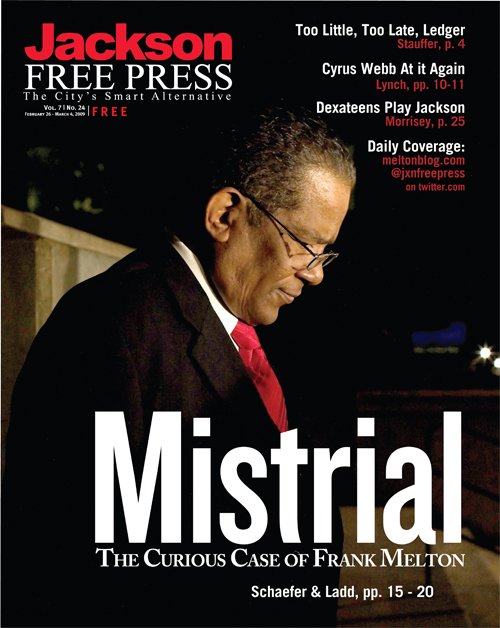

The first federal civil-rights trial of Jackson Mayor Frank Melton and his former police bodyguard Michael Recio ended Tuesday in a mistrial; attorneys plan to discuss a retrial next week. Court attendance had thinned over the lengthy deliberation process, and the handful of Melton and Recio's supporters present Tuesday remained mostly silent until adjournment.

"We got a new life," Melton supporter Robert Henderson said while leaving the courtroom. "Thank Jesus."

Henderson exhaled loudly and smacked a newspaper on his knee after hearing Judge Dan Jordan's ruling, but he was far more expressive than the mayor, who managed only a brief smile and did not answer questions outside the courthouse.

Jordan called the jury into the courtroom shortly before 11 a.m. after receiving a note saying that jurors were deadlocked for a second time. After the first impasse Feb. 19, Jordan had asked the jury to give the case further deliberation. This time, Jordan asked the jury foreman whether jurors had been able to reach a unanimous verdict on one defendant or one charge and whether further deliberation could help.

"No, your Honor," the foreman replied to both questions.

Melton and Recio are charged with unreasonable search and seizure for their roles in the Aug. 26, 2006, destruction of a duplex on Ridgeway Street. The two defendants face three specific counts: conspiracy against the constitutional rights of duplex owner Jennifer Sutton and tenant Evans Welch, the deprivation of those rights, and the use of a handgun in the commission of the first two crimes.

The Waiting Game

Over the jury's six days of deliberation, few hints emerged as to what jurors were thinking. Occasional notes from the jury revealed the topics of their discussions, but even the attorneys on both sides were hesitant to speculate.

"Anything could happen," Melton's attorney John Reeves told reporters outside the courthouse Feb. 18, after jurors sent a note requesting copies of Marcus Wright's testimony and the stipulations agreed to by both parties. "They're working hard. They're really considering the evidence. That's what you want in a jury."

The next day, jurors indicated in a note to Jordan that they were at an impasse. Jordan called the jury into the courtroom and reminded them of the trial's "considerable expense." He believed they needed more time to weigh the facts, he said.

"Keep in mind that each of you must decide the case for yourself," Jordan told jurors. "Do not hesitate to re-examine your own views and change your own opinion if you believe it erroneous."

Hours later, Jordan's instruction appeared to have broken some of the deadlock, as the jury asked for former Melton mentee Michael Taylor's testimony and a definition of conspiracy. Still, court adjourned that evening with no verdict from the jury.

On Feb. 23, they asked Jordan whether either defendant had to direct or point a weapon themselves to satisfy the fourth element of count two, which is the willful deprivation of rights. Jordan instructed the jury to convict Melton and Recio of a count only if each defendant's actions satisfied every element of the count. The four elements of count two are: the loss of rights; acting willfully; acting under color of law; and the use or threatened use of a dangerous weapon.

Jordan's response indicated that he wanted the jury to examine the element within the context of the full count. He told jurors that they had to decide whether Melton's and Recio's actions included "a use, attempted use or threatened use as defined in elements one, two and three of count two."

The Mayor's Mind

In their opening statements, both prosecutors and defense attorneys urged jurors to consider the defendants' state of mind when determining their guilt or innocence, specifically whether Melton and Recio had acted "willfully." In four days, prosecutors laid out a formidable set of evidence to show that the mayor had notice of proper legal avenues for pursuing a building's demolition, that he knew these proper procedures before the Aug. 26 raid and that he was drunk on the night of the raid.

When Reeves and Recio's attorney Cynthia Stewart opened their defense Feb. 17, they set out to prove that the defendants' intent was not a "bad purpose" to violate the law by suggesting that the mayor intended to stop drug activity at the house.

Defense attorneys repeatedly bumped into the limits Jordan placed on testimony about drug activity. Reeves and Stewart called a series of witnesses who said that they informed the mayor about drug use at the duplex and, in some cases, that they had bought and used drugs at the property. An order by Jordan prevented attorneys from asking about specific instances of drug use at the house, however, or about the house's smell.

On Feb. 17, Daniel Smith, a former drug user and current Hinds County inmate, offered similar testimony.

Smith told jurors that he was a former cocaine user, that he bought crack at the duplex on Aug. 26 and that he told Melton about it the same day. On cross-examination from the government, Smith acknowledged that he had never been arrested or investigated for his Aug. 26 purchase.

Stewart then called JPD Officer Quincy Russell to the stand for his account of Aug. 26. Russell testified that JPD dispatch sent him to Ridgeway Street to transport Welch and advised that Welch had outstanding arrest warrants. When Russell arrived at the duplex, Welch was standing on the sidewalk. On cross-examination by prosecutor Patricia Sumner, Russell said that Recio approached him and told him to arrest Welch. While searching Welch as part of his arrest, Russell found two crack pipes and a push rod for packing cocaine into a pipe. Russell confirmed to Sumner that dispatch had instructed him only to transport Welch, not to serve any warrants or conduct any searches. Normally, a JPD officer called to transport someone does not conduct the actual arrest, Russell said.

Jordan adjourned court until the next morning, when jurors heard from Christopher Walker, who lived with Melton periodically for more than a year and admitted to using drugs at the Ridgeway duplex. U.S. Marshals transported Walker from federal prison near Lafayette, La., where he is serving time for a gun charge.

During direct examination from Reeves, Walker admitted to using Ecstasy and marijuana at the house on numerous occasions and said that he informed Melton about drug activity prior to the raid. Walker also confirmed that he told Melton about "other illegal activity" at the house. Reeves and Stewart had wanted to specifically ask defense witnesses about prostitution at the house, but Jordan prohibited it in a court order.

The government's cross-examination sought to undermine Walker's credibility by bringing up his close relationship with Melton and his criminal history, some of which he described in a videotaped interview with Melton from the mayor's days with the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics. Referring to the "countless crimes" that Walker admitted to Melton, including participating in robbery and murder, and watching out for other murders, federal prosecutor Mark Blumberg asked Walker if he had been arrested for any of his confessed offenses.

"Everything I've been arrested for I've served time for," Walker said. "If I was released on a charge, it was 'cause it wasn't true."

After further pressing, Walker conceded that Melton had never arranged for his arrest for those admissions. Blumberg then brought up more recent evidence of a possible bias in favor of the mayor, in an exchange he had with Walker that morning. Walker had asked to speak with prosecutors the previous night but changed his mind the next morning.

"At that time you said, 'Because I feel friendly toward Frank Melton, I'll just stay with the story I promised to give.' Isn't that what you said?" Blumberg asked.

Walker replied that those were not his words. He acknowledged, however, that he was "a close friend of Frank's."

Law And Order, Drunks and Drugs

Delivering the government's closing argument, Blumberg appealed to jurors' faith in the rule of law, at one point hoisting a sledgehammer onto his shoulder to suggest the defendants' lawlessness.

"Today, in this place, the law is the only thing that matters," Blumberg said. "It's the thing that we wrap ourselves in to hold the chaos at bay."

In a decision reflective of the government's focus on the mayor, Blumberg split his closing statement into a longer 40-minute section primarily devoted to Melton and a shorter 20-minute statement that addressed Recio's role in the raid.

Calling Melton "drunk with power" and "a man with an outsized ego who got himself liquored up," Blumberg told jurors that the house's destruction was a show of force without any law-enforcement purpose. Any testimony about drug activity was simply misdirection, he said.

"It's about booze; it's about bluster; it's about grandstanding," Blumberg told jurors. "But what it wasn't about was drugs."

Moreover, Blumberg argued, Melton and his accomplices clearly knew the raid was wrong because they repeatedly lied about it afterward.

For the most part, Reeves left his client out of his closing statement, instead focusing on the credibility of the prosecution's witnesses and allegations of drug activity at the Ridgeway house. Jurors had to determine the mayor's intent by looking at the circumstances surrounding his actions, Reeves argued. He asked jurors to imagine a police officer letting a speeding car go unticketed because the driver was taking his pregnant wife to the hospital.

"Then you say, 'Oh, now I understand his intent," Reeves said. 'At first I thought he was breaking the law, but I understand now, the whole circumstance of it."

While challenging testimony by prosecution witnesses, Reeves reiterated the harsh tone of his cross-examinations. Lawrence Cooper, a self-employed mechanic and friend of Evans Welch's who described the raid, was "a full-time drunk," Reeves said.

Melton's attorney depicted duplex owner Jennifer Sutton, who cried on the stand while describing the damage to her house, as a negligent landlord trying to win money through civil lawsuits.

"She cried a little bit," Reeves said. "But I guarantee one thing: She'll cry to the bank and smile when the deposit is made of the taxpayers' money."

Even as he disparaged the credibility of witnesses, Reeves verged on the sentimental as he asked jurors to decide whether the mayor "had a bad purpose that day."

"You know, there's a place in all of us where the heart resides," Reeves told the jury. "It's deep down where your innocence is, where your hopes and fears are, and where you keep your most private things. We all have it."

"Ladies and gentlemen, Frank Melton's life is in your hands," Reeves concluded.

Reeves' closing statement took advantage of the defense attorney's folksy manner, Jackson attorney Rob McDuff said.

"I think he's very personable, and I thought he used that to good effect," McDuff, who watched the closing arguments, said.

Reeves reminded jurors of what they agreed to during jury selection: "You promised me on voir dire that you would stand by your convictions and not let anybody intimidate you and roll over on you. And I'm asking you to stand by your oath, and I know you will."

"If you don't believe the mayor of Jackson is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, it's your sworn obligation to vote 'not guilty' even if 11 other people are trying to get you to hurry up and get out of there because you've been in there a long time and the hour is late."

Blumberg objected twice as Reeves urged jurors to hold fast to their opinions. McDuff said that Reeves' tactic was proper and a common one for defense lawyers.

"It's often made in cases where the defense lawyer is concerned that the majority of the jury might be against their client," McDuff said. "They want to make sure that somebody who might be leaning in favor of the defense won't give in."

Concluding Michael Recio's defense, Stewart portrayed the mayor's bodyguard as a father struggling to do right in a compromising situation. The mayoral detail was "not a cushy assignment," Stewart said, but "a difficult job with a difficult boss."

Pointing out that the bulk of the government's case applied to Melton, Stewart argued that prosecutors had not proved her client searched or touched the Ridgeway house. Prosecution witnesses Lawrence Cooper and Michael Taylor both testified that Recio pulled an awning down, separating it from the rest of the house, but Stewart dismissed the testimony as inconsistent.

In the second half of his closing argument, Blumberg came to the defense of the prosecution's witnesses.

"The truth is that these people, these Welchs, Coopers and Suttons, are entitled to the same protection of the Constitution that both defense counsel asked you to apply when you walk into the jury room," Blumberg said.

Third Time's The Charm?

Immediately after granting the motion for mistrial and dismissing the jury, Jordan set the stage for a retrial, with an eye to the challenges he encountered in this first effort. He acknowledged that the heavy media attention the first federal trial generated will make it even more difficult to find a second unbiased jury pool. The first federal jury pool pulled potential jurors from as far as the Gulf Coast and the Louisiana and Alabama borders.

Jordan reiterated that a gag order prohibits all parties from making public statements about the case. He also addressed Melton's and Recio's conditions for release, reminding the defendants that they were still on bond and asking the attorneys to explain those conditions again to their clients.

Melton repeatedly tested the limits of Jordan's gag order prior to the trial's start, in public statements that alluded to acting with "evil intent" and some issues being "bigger than the Constitution." On Feb. 9, prosecutors also alleged that Melton violated the court order by contacting two witnesses in his own case: government witness Michael Taylor and Evans Welch. Melton visited Taylor, who used to live with him, in late January and brought presents for Taylor's infant son, prosecutors said. The mayor also attempted to personally serve a subpoena on Welch Feb. 8, despite an order forbidding him contact with witnesses. The government verbally asked Jordan to revoke the mayor's bond for the infractions but they declined to submit a formal motion, and the mayor remained free on bond.

Blumberg told Jordan that the government would discuss scheduling a retrial in a conference call with defense attorneys Monday, March 2.

Read more about the Melton trial at meltonblog.com and @jxnfreepress on Twitter.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 144101

- Comment

Love the title! LOL

- Author

- LatashaWillis

- Date

- 2009-02-25T22:13:11-06:00

- ID

- 144105

- Comment

Comparing what Melton & Co. did to an officer letting a speeder go because he's taking his pregnant wife to the hospital to deliver is laughable at best. Plus, delivering a baby is an emergency situation. Tearing down a suspected crackhouse isn't. Also, if crackhouses were such a problem, why wait over a whole year to tear one down.

- Author

- golden eagle

- Date

- 2009-02-26T09:13:29-06:00

- ID

- 144136

- Comment

Bracy Coleman's wife, Alice Coleman, just called to tell us that Bracy is not Michael Recio's father-in-law (as a caption that appears in the paper this week said). She was very gracious and said that has been a myth for years in Jackson, and that sources that say it's true are incorrect. The JFP asked Bracy himself if this was true during the trial, and he just laughed without confirming or denying. Other sources, however, confirmed that it was true. Alice Coleman say that Michael Recio's father and Bracy served in the military together for 30 years, and that is why Coleman is so close to Recio, whom she calls "Mike." She would not give Recio's father's name, saying that was up to him to do, and said she does not know the name of his wife Demetrice's father, who is divorced from her mother. Bracy Coleman sat in the courtroom daily with Recio's wife. We had heard a conflicting report that it was not true after publishing it, and I asked Mayor Melton this morning about it. He said that, to his best knowledge, it was not true, although it's been a rumor for years. I asked him to have someone contact us who could definitely confirm one way or another. However, Ms. Coleman (who is delightful; I'd never talked to her before) said her girlfriend suggested that she call to clear the myth up once and for all. We apologize to the family for passing along a myth as fact, and will publicize this next week in the print edition as well.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2009-02-26T16:22:24-06:00

- ID

- 144138

- Comment

Wow, this is news! I am glad that Mrs. Coleman was very gracious to you. But I wonder why they waited all this time to say anything about it. It was almost common knowledge that Coleman and Recio were father- and son-in-law.

- Author

- golden eagle

- Date

- 2009-02-26T16:49:41-06:00

- ID

- 144691

- Comment

To golden eagle, How would you feel if you picked up the paper and read that someone else is the father of your child? Common knowledge to whom?!! Certainly not the Coleman or Recio families and friends. It really doesn't matter how long wrong information is reported, IT IS STILL WRONG!!!!!!!!!!The appropriate thing to do would be go directly to the source and get the right information. You have gotten the correct information from a very valid source, so find some other "news" to focus on.

- Author

- redruby

- Date

- 2009-03-13T14:07:26-06:00