Neil White, a Mississippian who published newspapers and magazines in Oxford and on the Gulf Coast, was arrested in the early 1990s for "kiting" checkspassing them back and forth between banks without funds in either one to cover the other.

White was sentenced to a year in the Louisiana minimum-security prison, Carville, which also happened to be the last leper colony in America. A man used to a certain lifestyle, White showed up at prison in 1993 with a tennis racket in tow before being forced to realize that he was facing a tough year that would change his view on the world, and alter his family life.

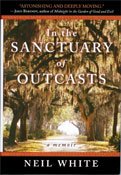

Years later, White published his memoir about his bizarre imprisonment, "In the Sanctuary of Outcasts" (William Morrow, $25.99, 2009), giving the reader a fascinating tour through both sides of Carville. White writes about his fellow inmates and the leprosy patients many of them feared with equal skill. Thanks to studious note-taking during his incarceration, his dialogue is sharp, detailed and often hilarious.

(White awkwardly defines the word "feces" for one of his fellow inmates: "'You know,' I said, pointing to my own rear, 'poop dook.' Then tentatively, 'Sh*t.'")

But White's honesty about the good and bad in himselfincluding the internal "disfigurement" at the root of his crimeis what sets this immensely reading and entertaining book apart. White is forced to face his self while in prison, even as he uses his publishing and entrepreneurial skills from the outside to help other inmates in ways they hadn't considered.

I sat down with White, who now owns The Nautilus Publishing Company in Taylor, Miss., to chat about the memoir.

1. Probably the most significant relationship in the book is the one you had with Ella, an elderly leprosy patient at Carville. Why do you think y'all were able to share such a connection? I assume she didn't have 5 a.m. coffee with just anybody.

I think the first was just fate, that I was assigned to the kitchen at 4 a.m. ... I was very fortunate to have access, and unsupervised access, in the kitchen to her. Ella was clearly more important to me than I was to her.

I don't think she looked at me and said, 'I'm gonna help this boy.' (She was) amazingly open, (with) no stigma about her disease. Others were shy, kept their heads down (and) didn't give anyone a chance to look them in the eye.

2. What is the most important lesson you learned in prison?

[T]hat's a really hard question. But I usually give two answers. First, the people who are most worth getting to know are covered with scars. Second, this isn't a lesson but an image that I'll always go back to Ella in her crank wheelchair, veering off and correcting. That's a great metaphor for my life.

3. How and when did you decide to write the book?

Why did you wait 12 years after your release? I always wanted to write the story, at least for my kids. (And) the writing of the book was very healing. The publishing went counter to many of the lessons I learned (at Carville, about not seeking attention. But) a few people had been reading some passages, and they really encouraged me to share the story. They felt it would be healing, not damaging.

I went to great lengths to be truthful and accurate about what I did and not gloss over it, and not to paint anybody else as the bad guyexcept a few inmates who actually were bad guys.

4. What, if anything, are you going to write next?

I'm not sure. I wrote a play (based on my time at Carville) in 1998. I may revisit that.

I have an idea where I make the main character Ella, and she sees all these boys coming in, and she tells the story.

5. You've said you don't really want anyone to make a movie about the book.

(A filmmaker would probably) make me much worse before (Carville) and much better after, or they'd make the inmates very grotesque like the Elephant Man, chasing inmates down the hall. Once they buy the rights, it's theirs.